Walking may be good for your health, except on one seemingly gentle coastal path in Great Britain. It is a path known for whisking even the heartiest of people to a murky demise.

The death toll is estimated to be around 100 souls, but it could be much higher. After all, the cold North Sea has a way of hiding bodies.

The Broomway’s six miles in length have been known as “the most perilous byway in England.”

For centuries, going back to Roman times, it has been the pedestrian route between Essex, England, and the once-agrarian bounty of Foulness Island.

The county of Essex in England. Photo by Nifanion CC BY SA 3.0

The route got its name from the twiggy broomsticks once used to mark the route over the tidal plain between them. Why so dangerous? Let us list the ways.

First, just getting to the Broomway involves a genuine risk of getting caught in quicksand.

The Broomway. Photo by Liz Henry CC By 2.0

Stepping off of the rubble-strewn causeway that leads there will land you on the treacherous sucking mires of the Black Grounds, or as locals know it, the Coffins.

And while you aren’t likely to fully submerge, you’ll be trapped for the incoming tides to finish. How’s that for a mood setter?

Once you hit the tidal plain and start walking, you have, at best, a four-hour window to complete your trek. And you’d better know your tide tables.

From a distance, someone traversing the Broomway appears to be walking on water, with two to three inches underfoot at any time. But that water can rise almost as fast as you can take a breath.

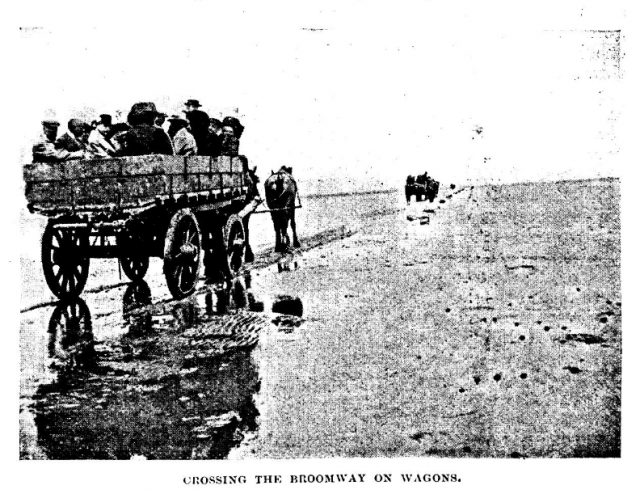

A pre 1922 trip by the Essex Field Club across the Broomway by farm wagon

The incoming tide pushes in across the flats at a speed no one can expect to outrun, and the current is not one you can break free of. And even if you were of superhuman speed or strength, the cold waters would certainly chill the life right out of you.

The gray can kill you, too. Yes, the stark gray of mists that roll in from the North Sea.

In this surreal curtain, any trace of higher ground disappears and the sea, the sand, the standing two to three inches of water you are constantly sloshing through, and the sky all become a uniform pale slate gray, a color undecided and experimenting between light and dark.

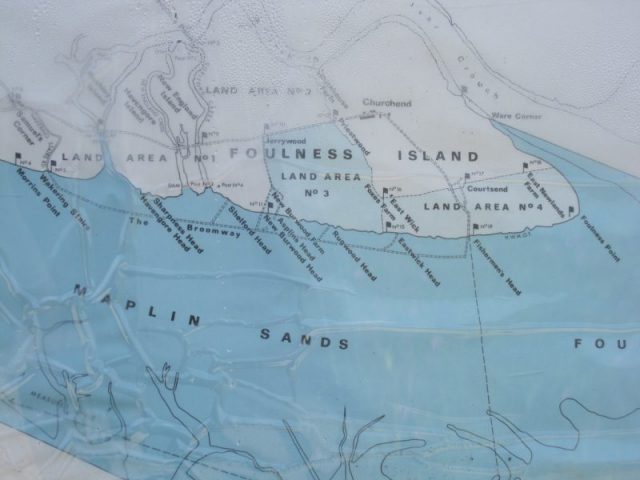

The Broomway marked on a map. Photo Helen Miller CC By-SA 2.0

At that point, up, down and any cardinal direction around you is indistinguishable from anything else.

Many people have become disoriented and wandered off course, delaying their exit long enough that the incoming tide and its accompaniment of dangerous eddies drowns them.

The headway at Wakering Stairs, the current southerly starting point of the Broomway. Photo Helen Miller CC By-SA 2.0

There’s one more potential killer, and this one is born of man, not nature. It’s unexploded ordinance.

Foulness Island is now owned by the Military of Defense and is operated by a private contractor for testing explosives and even aircraft ejection seats.

Access to the island is often restricted, and warning signs are posted everywhere about the dangers of moving or touching, or walking on or even near unexploded ordinance.

Although access is limited, people can still walk the Broomway, although hiring a knowledgeable local guide is recommended. Even so, longtime locals–especially the thrill-seeking kind–have been known to perish on the route. In the late 1800s, some farmers were known to wait until the last minute to race the tide.

A local surgeon, Charles Miller, traveled the Broomway on horseback as duty required. It was reported that he regularly would get lost in the fog, and when he did, he would drop the reins and leave it to his horse’s unerring instincts to get him back safely.

Warning sign – The Broomway. Photo by Liz Henry CC By 2.0

One sportsman who got caught in fog on the Broomway while hunting wildfowl was very nearly added to the death toll, except for help that got him back safely.

He later wrote that the situation was so dire that he considered tying his arm to the muzzle of his gun and driving it into the sand and muck, just so his body would not be lost to the sea.

A walker on the Broomway. Photo by Qneiform CC BY-SA 3.0

On the list of the Broomway dead are two girls, who in 1836 were found dead of exposure–not drowning–after expecting to meet their young men on the other side.

Among the more recently killed was an Irish policeman who was there to serve papers. He shrugged off warnings of the dangers.