The use of camouflage to hide oneself from an opposing person or force is nothing new. Since time immemorial, people have taken cues from the natural world and used concealment methods and tactics to hide their position and movement. However, this has evolved into being more than face paint, fabric, and tree branches, and some methods are quite innovative.

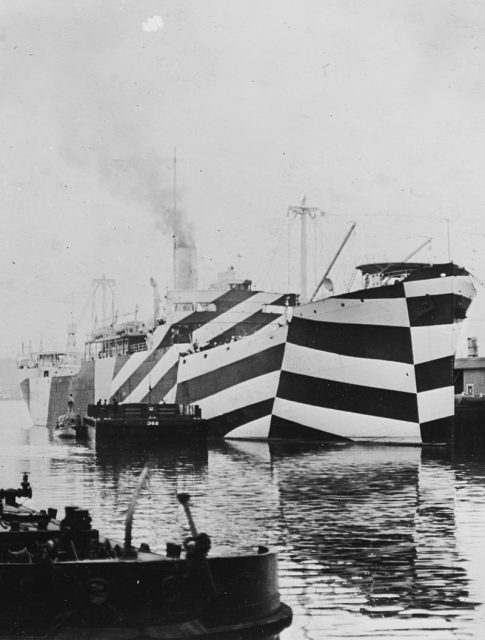

Green or drab uniforms replaced the previous red or blue versions in the 18th century, and the regular use of camouflage in military units was born. This soon included equipment, buildings, and even aircraft and ships. “Dazzle” paint schemes were used on ships during the First and Second world wars. While the literally dazzling pattern didn’t make the ships disappear altogether (that would be a feat!), it did make them appear smaller, therefore harder to hit. This pattern even inspired the Chelsea Arts Club “Dazzle Ball” in the UK in 1919.

SS West Mahomet in dazzle camouflage, 1918

During the world wars, both sides often fabricated tree stumps out of wire and papier maché to hide themselves from snipers and observers. They were designed to look like other trees on no-man’s land–battle damaged and stripped bare. However, because they had to be placed in flat, exposed areas, the replacement of real trees with fake versions was dangerous work. One such tree is on display at the Australian War Memorial, in Canberra, and it is signed by a soldier, Private Frederick Augustus Peck, who was killed three months after he signed his name.

The Schenkl projectile, used in the American Civil War, used a papier-mâché sabot

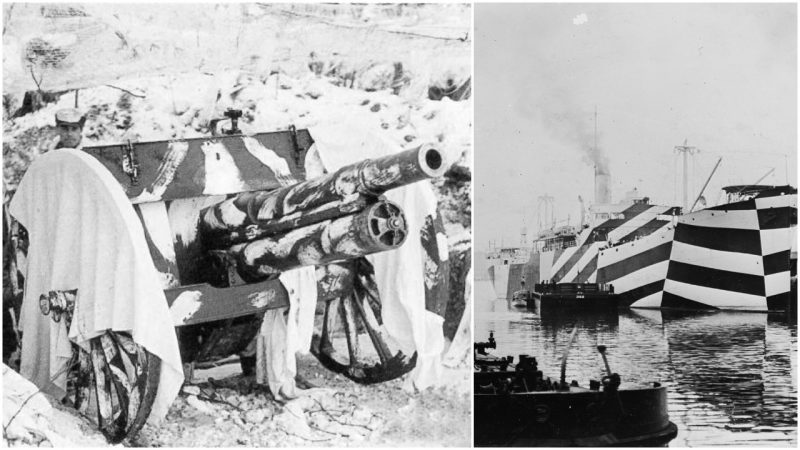

It has not only been green and leafy areas that required the use of camouflage. During the First and Second World wars, forces fighting in the colder regions of the world used winter camouflage. While one may think that it would only need to be white, it often included some green and black, taking its cues from winter plumage and fur of arctic animals. Forces deployed in northern areas today still use arctic camouflage on a regular basis.

Even animals have been camouflaged. English troops fighting in Egypt during World War I sometimes painted their horses as zebras, making them almost invisible in the tropical foliage. This may have inadvertently had other advantages. In recent years, it has been claimed that a zebra’s stripes make it less attractive to pesky, and disease-carrying, horseflies–an added bonus when you’re in the tropics.

Finnish artillery during the Winter War, showing improvised snow camouflage made from bedsheets and whitewash

Camouflage was mostly used on guns and equipment during World War I, and, like today, each country had its own pattern. However, sometimes it was necessary to deceive the enemy with visible decoys – perhaps the opposite of camouflage. This was done by using mannequins, dummies, and cutouts.

There is recorded evidence that mannequins were used by the ancient Chinese during the Battle of Yongqui. Scarecrows were lowered along the castle walls to draw enemy arrow fire. Mannequins were also used to draw sniper fire away from soldiers in World War I trenches. Any sniper firing at one of these fake soldiers would give away his own position, making him vulnerable. Likewise, Finnish forces are known to have used mannequins in a similar way during the Winter War (part of World War II). The figures would, like the World War I versions, draw sniper fire, and allowed the Finns to return fire upon the Soviet soldiers.

Mannequins

One highly unusual piece of camouflaged equipment, a Land Rover used by the British SAS during World War II, was painted a dusky pink. Its curious color was perfect for the African desert where it was used, especially in the early morning and at dusk.

Today, military forces are still using and developing methods of concealment, from special paint to pixelated camouflage, and more. In the future, “invisibility” clothing may be used. Perhaps J. K. Rowling was on to something.