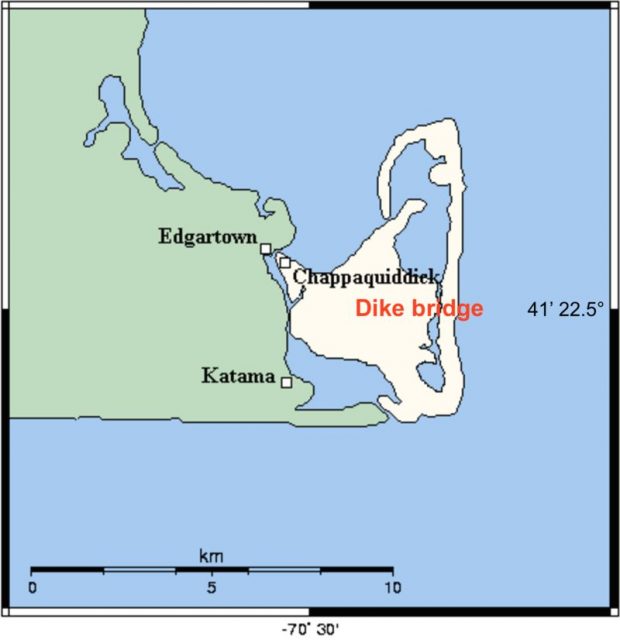

On the morning of July 19, 1969, the discovery of a dead 28-year-old woman, Mary Jo Kopechne, in the back seat of a car owned by Senator Edward M. Kennedy, one that had apparently crashed into the water off Dike Bridge on Chappaquiddick Island, Massachusetts, did more than destroy any chance of Kennedy becoming the third brother of the famous family to run for the U.S. presidency.

The fateful car accident, commonly referred to as simply “Chappaquiddick,” exploded into a political scandal and then a controversy over a woman’s death that has never gone away, but instead gained momentum.

Almost 50 years later, attention is renewed with the release of a new film, Chappaquiddick, starring Kate Mara and Jason Clarke; the re-publication this spring of the book Senatorial Privilege: The Chappaquiddick Coverup, the struggle over which reportedly drove its author, Leo Damore, to despair and suicide in 1995; and the debut in May of a podcast series about Kopechne’s death titled “Cover-Up” created by Peoplemagazine.

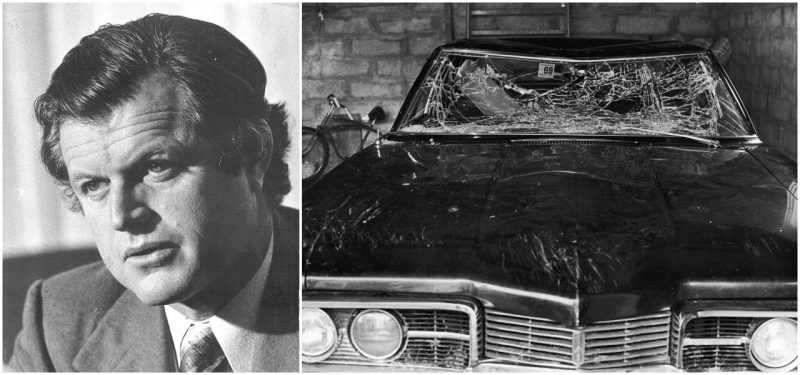

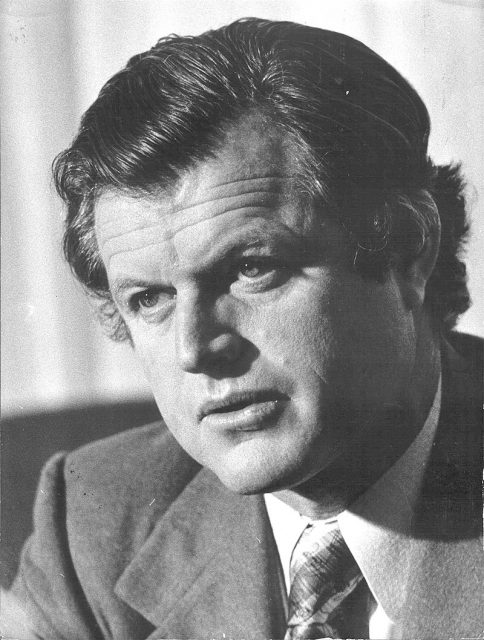

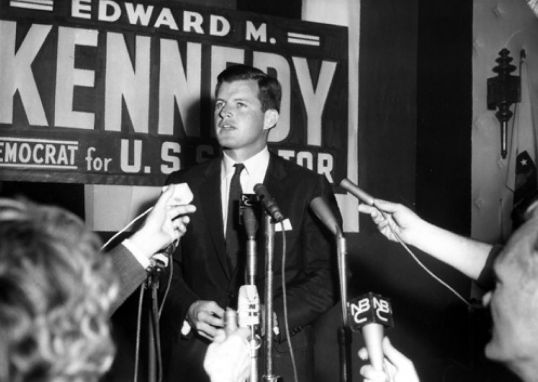

Edward Kennedy. Photo by Stevan Kragujević CC BY-SA 3.0

There’s the official story of a young woman left to die in a car underwater after Kennedy, who, by his own admission in a televised statement, gave up in his efforts to get Kopechne out of the car. “In a state of exhaustion and utter alarm,” the Massachusetts senator left the scene and did not seek the help of the police or report it to authorities.

“And then there’s another story,” said People’s East Coast editor Liz McNeil in the podcast. “One of power and privilege, a woman’s death overshadowed by one man’s political future, leaving behind suspicion of conspiracy, corruption, and a cover-up.”

Senator Kennedy’s car with smashed windshield parked in a garage after his accident at Chappaquiddick, Massachusetts, 1969. Photo by Santi Visalli /Getty Images

There’s no question that in 2018 a married senator with a young unmarried woman in the car who met such a terrible fate would have been subjected to far more rigorous treatment, by both the legal system and the media. Moreover, the existence of cell phones and surveillance cameras could have made a critical difference in 1969.

As it is, there are aspects of Chappaquiddick that seem to defy explanation.

In 1969, Kennedy pleaded guilty to leaving the scene of an accident and was given a two-month suspended sentence and a year probation by Edgartown District Court Judge James A. Boyle. He returned to the Senate to resume his life; his wife, Joan, was by his side at public appearances.

The Dike Bridge, Chappaquiddick, pictured here in 2008 with a guardrail.

Subsequent inquests in 1969 and 1970 to discover the truth about what happened ultimately went nowhere. A grand jury convened but returned no indictment of graver charges against Kennedy.

The parents of Mary Jo Kopechne filed a petition to bar an autopsy, and exhumation petitions were denied by the courts.

Stephen Kurkjian, a longtime investigative reporter for the Boston Globe, recently wrote, “A fair reading of the case showed that the evidence did not justify bringing tougher charges such as driving to endanger, or even manslaughter. But leaving the prosecution in the hands of a politically-savvy Democratic loyalist ensured that unanswered questions were not pursued, and it also ensured that those questions would persist through the years.”

The Kennedy brothers

Those who advised Kennedy and reportedly pressured or misled others in the Kennedy investigation had a lot to lose. The senator was being groomed to run for the presidency in 1972.

The speechwriters who once worked for President John F. Kennedy were convened to craft Ted Kennedy’s televised speech to the nation about the tragedy.

“Everyone was on board with the Ted Kennedy Democratic Party,” said Jason Clarke, who plays Kennedy in the new film, in an interview with Peter Travers on ABC’s “Popcorn.” “If he did good, they all did good.”

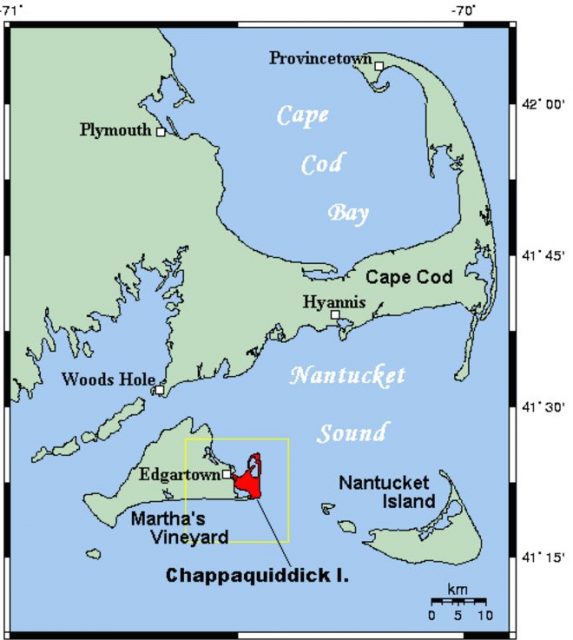

Map of Cape Cod with Chappaquiddick. Photo by Soerfm CC- BY-SA 4.0

Mary Jo Kopechne, born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, was described in the Cover-uppodcast as “a small town girl with big dreams. She was passionate, she was political, she worked 24/7, and she was a true believer. She played a key role in Bobby [Kennedy’s] campaign, handling correspondence, researching convention delegates, and canvassing for votes.” The women campaign staffers who performed these duties were known as the Boiler Room Girls.

Kopechne was at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles the night that Robert Kennedy, campaigning for president, was assassinated in 1968, and she was by all accounts devastated by his death. So was Ted Kennedy, who for a time was convinced that he would be shot and killed just like his brothers John and Robert.

In the summer of 1969, Kopechne and the other Boiler Room Girls were invited to a reunion cook-out on Chappaquiddick Island, off the East Coast of Martha’s Vineyard, that coincided with Ted Kennedy’s competing in the Edgartown Yacht Club Regatta.

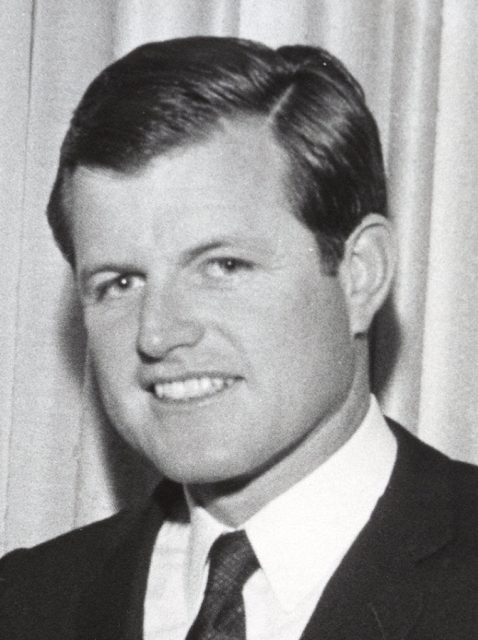

Ted Kennedy, 1967

The party attendants were six unmarried women and six married men who included Kennedy.

In his later statement, Kennedy denied any impropriety to the situation. Reporters noted that there were an enormous number of liquor bottles and beer bottles found in the garbage cans outside the party.

According to the official account, Kennedy and Kopechne left the party together at about 11:15 p.m. because she had asked him to drop her at her hotel.

Kopechne reportedly did not tell her friends she was leaving the party and she did not take her handbag or the keys to her hotel room. In one of the most confusing aspects of the case, the handbag of another Boiler Room girl, Rosemary Keough, was later found in the car.

Map of Chappaquiddick. Photo by Soerfm CC- BY-SA 4.0

Kennedy said at the inquest that he meant to drive to the ferry but took a wrong turn on an unlit dirt road and then drove off the Dike Bridge, the car flipping upside down in the water. He also testified that after he escaped from the car but was unable to free Kopechne, he returned to the party on foot and asked two of the men to help him rescue her.

When they were unable to get to Kopechne in the car because of currents in the water, Ted found a way back to his hotel and only then did he not notify the police. The next day he chatted before breakfast with fellow guests as if nothing were wrong.

‘Dike House’ along Dike Road. People later wondered why Kennedy did not stop in the house to seek assistance after the car accident.

Two locals contemplating fishing off the Dike Bridge spotted the overturned car by 8 a.m. the following morning. It was only after the police called in the plates on the car that they discovered it belonged to Senator Kennedy and calls were made to his staff.

Kopechne’s lifeless body was found in the back of the car, “definitely holding herself in a position to avail herself of the last remaining air that had to be trapped in the car.”

When Kennedy showed up at the police department later that morning, he appeared uninjured and even well rested.

“Nearly 50 years later, there are a few things everyone can agree on,” said McNeil in Cover-up. “It was a hot summer night, the water was calm, Mary Jo Kopechne attended a cookout at a small rental cottage and the next morning she was found dead in a submerged car at the bottom of a tidal pond.”

TedKennedy 1962

How long Kopechne survived in the back of the car, who drove the car and actually was in the car along with her, and whether any attempts really were made to rescue her are questions to which there are many possible answers and no confirmed truths.

Kennedy went on to become one of the most respected legislators of the late 20th century, pushing for landmark bills.

“If the negative image that the film projects of Kennedy’s actions at Chappaquiddick is based on solid reporting, it fails to reconcile that image with the extraordinary public life he led following the accident,” wrote the Boston Globe’s Stephen Kurkjian. When his achievements in the Senate are considered, “they show that Kennedy certainly found purpose by staying in public life, and that the country was well-served by that decision.”

Senator Kennedy died of cancer in 2009 in his home in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts.

Nancy Bilyeau, the U.S. editor of The Vintage News, has written a trilogy of novels set in the court of Henry VIII: ‘The Crown,’ ‘The Chalice,’ and ‘The Tapestry.’ The books are for sale in the U.S., the U.K., and seven other countries. For more information, go to www.nancybilyeau.com.