As the sole female monarch in the history of Norway and deservedly recognized as one of the most intriguing and skillful political figures in Scandinavia, Queen Margaret I of Denmark proved to be a brilliant tactician. Her rightful heir, Eric, who succeeded her? Not so much.

Margaret I became the first rightful ruler of all of Scandinavia and was well respected by almost everyone in Norway, Denmark, and Sweden. She was “Our Mighty Lady and Sovereign” to the people of the three kingdoms in 1387, when her diplomatic skills and expertise persuaded Sweden to join the Danish-Norwegian alliance, laying the foundations for the Kalmar Union, the one and only Nordic union known to this day.

Both she and her sister were Danish princesses and daughters to King Valdemar IV of Denmark, who did not father a male heir, so instead, he promised his older daughter, Margaret, to Haakon Magnusson the Younger, the King of Norway, to increase his fortunes. They were married when Margaret was just 10 years old. Their only child, Olaf, was to be king of both Norway and Denmark when his father died in 1380 and the kingdoms accepted him as a future ruler. In the meantime, until he legally could rule, his mother did.

Oil portrait of King Eric the Pomeranian of Scandinavia in Darłowo Castle, as released by image creator Ristesson.

But it wasn’t meant to be for young Olaf. He was a king for only two years; in 1387 he passed away. With his father dead as well, the legal right and the full responsibility to rule the kingdoms fell on the shoulders of his mother, who made sure to create a strong bond between the kingdoms. It was a union that would remain for five long centuries, until the Danish-Norwegian alliance came to an end in 1814.

In 1387 she persuaded the Swedish (who at the time were already on the move to depose their king) nobility to join her alliance, and in 1388 to sign the Treaty of Dalaborg. Margaret became Sweden’s “sovereign lady and rightful ruler.” Now she was queen to the three great Nordic kingdoms.

All they wished in return was a rightful king to succeed her at some future point in time. A mighty one that would keep them united and treat them equally. And with Olaf, her only child, deceased, it seemed her sister’s grandson Eric was the nearest candidate to take the place.

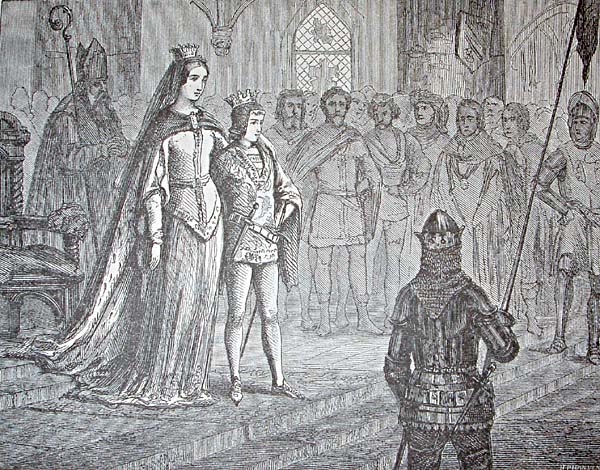

Eric of Pomerania with Margaret I of Denmark at his coronation.

Eric of Pomerania was no more than six at the time when he was bestowed as the future king by Margaret. He was 14 when he married his 12-year-old English wife, Princess Philippa, and just 15 when he was crowned as sovereign king in the ancient town of Kalmar, Rikets Nyekel–the key of the kingdom. He was to be their great king.

It was Trinity Sunday on June 17, 1397, and his coronation took place in front of every nobleman, bishop, priest, and almost anyone really that meant anything in Scandinavia, officially marked the beginning of the great Kalmar Union between Denmark, Sweden, and Norway.

However, Margaret effectively continued to rule until she died in 1814. This new, handsome boy, as he was described, but not turning out to be so shrewd, as time proved, took her place. He was 33, but unfortunately, he was never able to follow Margaret’s vision nor walk her path towards unity. On the contrary, he paved the road that led the union to collapse.

A contemporary depiction of the king.

As soon as he sat on the throne, he tried to strengthen the empire and expand it even further by marching towards the Jutland Peninsula (Schleswig) and the Holstein region (Northern Germany). After two long decades of war, he managed to win and defeated the Hanseatic League, a powerful confederation of German merchants guilds. He then imposed a policy that meant every ship that wanted to enter or leave the Baltic Sea was obliged to pay him, and the Nordic Empire, a toll in order to pass through the strait between Denmark and Sweden.

He believed he was building a powerful empire and saw his offensive strikes as the best way. The tax was supposed to be a fresh income that was much-needed to maintain control and keep everyone safe. However, by doing so he only made enemies out of the German counts that were previously on good terms with Margaret as well as from almost every powerful trade merchant who wanted passage and was not willing to pay a tax, including Nordic ones.

In addition, wars are expensive. And this one lasted for two and a half decades. Taxes that already existed were raised and new ones were implemented, but it was all for the sake of the Empire, according to him.

It took a couple of years, but people inside the union saw through his “all in the name of a great unity” racketeering. After all, both nobles and commoners were “investing” their own money in a war that eventually led them to have more hefty taxes and boosted prices all over, while the king, to their eyes, was getting richer and richer. As he was growing in money and power, everyone else was losing theirs.

By the 1430s he was on bad terms with everyone around and inside the Union. People were fed up.

Eric’s grave at St. Mary’s in Darlowo

The Swedes were the first to feel the injustice and do something about it. They were taxed as everyone else was and were dying in his wars just as much. But Eric was appointing Danish representatives in almost every lucrative and well-respected position in the kingdom. Swedish castles were run by Danes and not in a way Swedes wanted. They asked for new constitutional laws to grant their kingdom’s autonomy and self-governance. Eric refused. This lead to a great rebellion in 1434, the Engelbrekt Rebellion, with Engelbrekt Engelbrektsson, Sweden’s freedom fighter for the common man, at its helm.

King Eric’s absolutist and autocratic rule over their land was put an end, as was his money-gathering. The freedom fighter was assassinated, the rebellion continued, and Eric was eventually dethroned in Sweden in 1439, and in Norway and Denmark right after.

Statue of Eric at Darłowo Castle.

Eric was forced to flee Copenhagen, and even lead a life of piracy for a couple of years trying to win back his throne.

According to the story, Eric, who didn’t father any children, left his wife behind as he fled the capital and became the leader of a guild of privateers and marauders: the Vitalienbrüder, or Victual Brothers. This pirate organization ravaged the Baltic Sea and helped former King Eric continue his taxation endeavors, in a manner of speaking, for a couple of years. He tried to sit on the throne once again but never did. He was succeeded in Denmark, Sweden, and Norway by Christopher III of Bavaria, and no one knows what happened to his wife.

Eric died in Pomerania in 1459 with a tarnished name, a wife left behind to meet her own demise in a kingdom “under fire” caused by his own wrongdoings, and a great legacy that was left for him to run, ruined.

The union never really recovered after his despotic and totalitarian reign and died off completely in 1523.