Over the years, people have gone down Niagara Falls in a wide variety of contraptions: wooden barrels, a rubber ball, a kayak, even a Jet Ski. But the most impressive descent took place on July 9, 1960, when seven-year-old Roger Woodward went over the Falls wearing little more than a life jacket. It would become known as “The Miracle of Niagara.”

It began on a sunny July morning in 1966. Roger and his 17-year-old sister Deanne joined a family friend, Jim Honeycutt, 40, on his 14-foot aluminum boat, equipped with an outboard motor, for a trip down the Niagara River, high above the falls.

The Woodward family had moved to the area a few months earlier and they thought an outing to the Falls would be a nice way to celebrate Deanne’s birthday. None of them knew they would soon be experiencing the mighty Niagara from a terrifying vantage point.

Niagara Falls, aerial view.

Honeycutt piloted his boat past the Ontario Hydro control dam. Only a mile from the brink of the Horseshoe Fall, on the Canadian side, it provides a more even flow of water over the falls. Not many boats venture past this point, where the friendly river turns turbulent. But Honeycutt under-estimated the river’s strength — and the danger that came with it.

Soon, the boat’s passengers could see Goat Island, dividing the river into two sets of rapids, one going over the American Falls, the other the Horseshoe Falls. In the distance, the three could see the spray caused by massive amounts of water falling over the falls and crashing into the river below.

Now realizing the danger, Honeycutt desperately tried to turn the boat around and head for Goat Island, which extends at the very edge of both the American and Horseshoe Falls. It was too late: The boat was in the rapids now, being tossed around helplessly.

Goat Island, New York, from Skylon Tower. Photo by Chris Oakely CC BY 2.0

There were two orange life jackets in boat. Roger was already wearing his; Deanne struggled to fasten hers. Water pounded the boat, rushing over the sides. Soon it capsized and its passengers were tossed into the swirling water.

Deanna could make out her brother’s orange life jacket, bobbing further away from Goat Island, toward the Horseshoe Falls. The girl swam furiously, trying to reach the edge of Goat Island, where a crowd had gathered, looking on in disbelief.

Suddenly, a man rushed to the railing: John Hayes, a truck driver and auxiliary policeman from Union, NJ. Climbing over the guardrail, he extended one arm as far as he could, while grasping the rail with the other, but the girl was out of reach.

Niagara Falls survivor on vacation. Roger Woodward, 7 year old who suffered almost no ill effects from a plunge over Niagara Falls. Bettaman/Getty Images

Refusing to give up, Hayes ran ahead on an 18-inch ledge a few inches above the water. “Kick harder,” he pleaded. Anchoring one foot around the bottom rail, he again stretched out his arm. Deanne’s fingers clasped his thumb and Hayes was able to stop her, just feet from the brink of the Falls, but he couldn’t pull her out of the violent current. Help came from another hero, John Quattrochi, of Pennsgrove, NJ, who climbed over the railing, grabbed her other hand, and helped Hayes pull her to safety.

Meanwhile, her brother and Honeycutt were still in a fight for their lives. When they were first pitched into the water, the boy was holding onto Honeycutt, but the turbulent water ripped them apart. The rapids carried the two away from Goat Island and closer to the center of the Horseshoe Falls, where they shot over the brink, into the mist below.

Fate was with Roger that day. The boy could have been hurled into the hundreds of rocks jutting from the water’s surface. But because he was wearing a lifejacket, and because of his slight, 55-pound frame, Roger rode the crest of the Falls and was shot beyond the pounding water. Honeycutt, heavier in weight and not wearing a life jacket, dropped straight down and was dead within seconds, as the current sent his body deep into a 200-feet-deep well.

Roger was alive, but not yet out of danger. Bobbing in the water, he could make out the outline of a boat through the heavy mist: the Maid of the Mist, taking tourists close to the base of the Horseshoe Falls. Captain Clifford Keech was about to turn his craft away from the Falls when he spotted the orange jacket.

He maneuvered his boat to pick up the boy as he drifted past. The boat’s crew flung a life preserver in Roger’s direction — once, twice, then, on the third attempt, Roger was able to grab on and was pulled safety. He was lifted out of the water and placed gently onto the deck, to the amazement of the boat’s passengers — many of whom didn’t realize the boy had come from over the Falls.

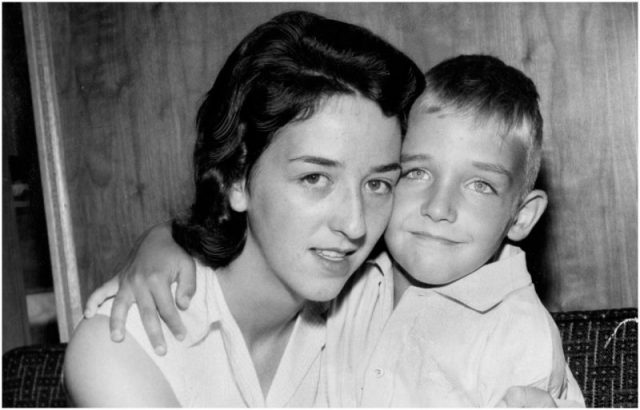

Deanne and Roger Woodward. Bettaman/Getty Images

Surprisingly, Roger’s trip over the falls left him relatively unscathed, save for some minor bruising on his jaw and around the right eye. His sister Deanne, recuperating in another hospital, was equally fortunate, coming out of it with just a small cut on her hand. Jim Honeycutt’s body wouldn’t surface for four days, finally released by the current beneath the falls.

Newspapers couldn’t get enough of the only known survivor who beat the mighty Niagara. But the publicity proved too much for Roger’s parents, and the Woodward family would leave Niagara in 1962. Roger, who now resides in Alabama, and his sister Deanne, went decades barely speaking about their brush with death.

Years later, when Roger was in high school, a reporter managed to track him down and encouraged the boy to share his story. “The people I went to school with didn’t know anything about it,” said Roger. Though he kept a low profile for years, his three sons were more willing to share their dad’s remarkable story as a Niagara survivor. As Roger would put it: “I was a pretty good show-and-tell piece in school.”