Venetia Burney was an 11-year-old girl eating breakfast with her mother and grandfather in Oxford, England, in March 1930. Her grandfather, a retired head Oxford librarian, read aloud some exciting news in the London Times: Scientists at Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, had photographed a planet long suspected of lying beyond Neptune. The Observatory’s founder, Percival Lowell, had theorized about a distant planet, and though he was no longer alive, astronomers had been on the hunt ever since.

The Burneys, all fond of astronomy, were thrilled by the report. “It is probably larger than the Earth, but smaller than Uranus,” Venetia’s grandfather read. He wondered aloud what the planet would be called.

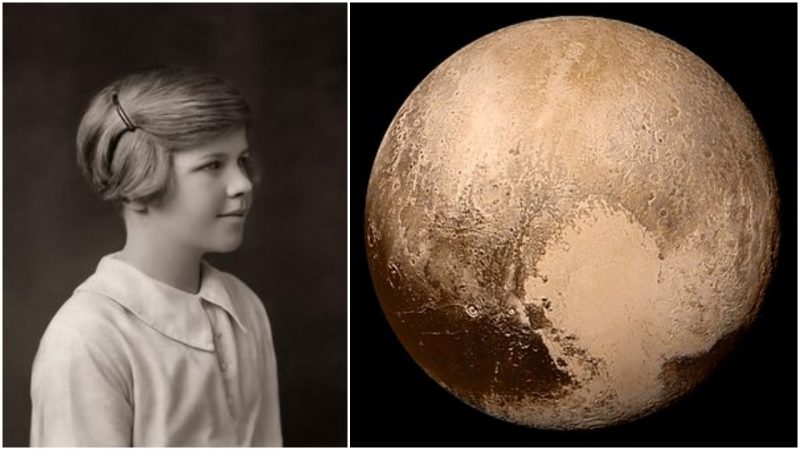

“After a short pause, I said, ‘Why not call it Pluto?’ ” Venetia recalled in a NASA interview in 2006.

A precocious learner, at age 11 Venetia was familiar with the solar system, the names of planets and moons, as well as Greek and Roman legends. With a school class, she’d been on walks in the university park in which her teacher had described the relative distance between the planets and the sun. All of these factors played into Venetia’s conjuring up the name Pluto.

Venetia’s grandfather, Falconer Madan, thought naming the planet Pluto was such a splendid idea, he wrote a letter to an astronomer pal of his at Oxford, who agreed, writing back, “I think PLUTO excellent!!” The

Full-disc view of Pluto in near-true color, imaged by New Horizons

Oxford astronomer promptly cabled his peers at the Flagstaff Observatory: “Naming new planet, please consider PLUTO, suggested by small girl Venetia Burney for dark and gloomy planet.”

Little did they know that a debate was raging among astronomers over what to call the newly discovered planet: Kronos? Zeus? Minerva? Atlas? Persephone? Pluto, thanks to its connection to the underworld, was considered a long shot by some. Scientists at Lowell Observatory, however, voted unanimously for the name Pluto, in part because the first two letters, PL, were seen as homage to their founder, Percival Lowell.

Pluto officially received its name in a ceremony on May 24, 1930. Venetia herself received a 5-pound note from her grandfather.

Falconer Madan also wrote a letter of gratitude to Venetia’s teacher, saying “I really believe that had Venetia been under a less capable and enlightened teacher than yourself, the suggestion of Pluto would not have occurred to her,” according to Mental Floss. He also sent money, which was used to requisition a classroom phonograph, which the teacher named Pluto.

Mosaic of best-resolution images of Pluto from different angles

“Pluto is an excellent name, for two reasons,” author Neil deGrasse Tyson told the New York Times in 2009. “First, it’s a Roman god, as are the rest of the large objects in the solar system, so it conforms to the rules of the time, and second, Pluto is the god of the underworld, a distant place you don’t want to go to. Who could not love the name?”

As it happens, Venetia was not the only one in her family to name a celestial body. Her great-uncle, Henry Madan, a Science Master of Eton, had in 1877 suggested names for two dwarf moons of Mars, Deimos and Phobos, meaning terror and fear.

Artistic comparison of Pluto, Eris, Makemake, Haumea, Sedna, 2002 MS4, 2007 OR10, Quaoar, Salacia, Orcus, and Earth along with the Moon. Photo:Lexicon CC BY-SA 3.0

Venetia grew up to become an accountant and economics and math teacher married Maxwell Phair, who would become housemaster of Epsom College, and had one son. Later in life, Venetia Phair downplayed the significance of her naming the planet, though she would correct people who thought she’d named it after the Walt Disney dog. Disney’s Pluto didn’t get his name until 1931, well after the planet. She died in 2009 at the age of 90.

In 2006, speaking to NASA about the naming, she confessed that she didn’t remember much. “I can still visualize the table and the room, but I can remember very little about the conversation.”

Phair took it in her stride when Pluto was demoted to “dwarf planet,” according to the New York Times. Perhaps she didn’t mind as, by then, she had her own name in the sky: an asteroid called 6235 Burney.