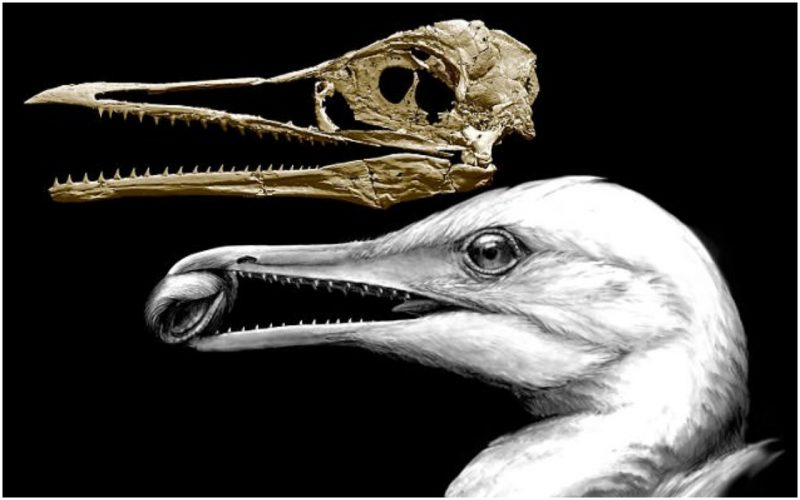

A very early bird species known as Ichthyornis dispar is helping scientists answer questions on how our avian friends evolved from dinosaurs. Fossilized specimens of four skulls, mostly fragmented, of this Cretaceous period seabird species have been used by both U.S. and U.K. scientists to complete a 3-D reconstruction of almost the entire skull. The results have surprised everyone: Although Ichthyornis dispar sported the fairly elegant body of a seabird, it still kept dino features such as monstrous teeth.

Ichthyornis dispar appeared as early as 100 million years ago. The first fossils of it were retrieved in the 1870s in Kansas, during an excavation effort that was led by an eminent American paleontologist of the day, Othniel Charles Marsh, according to the National Geographic. The specimens were praised at the time by figures such as Charles Darwin as authentic evidence of the evolutionary process, a subject about which he wrote two decades prior.

Of course, when scientists first looked at this 19th-century specimen of I. dispar, they believed the fossil samples were the remains of two different species; if the body belonged to a bird, the jaw, they ruled, was that of a marine reptile. Eventually, it was concluded this was one creature, but the upper jaw of the mouth was missing elements from its definite composition. According to the Smithsonian, this fueled the assumption that early birds sported an upper jaw that was fixed.

After the latest research, which included scanning technology and revisiting old fossil material, like the Kansas specimen from Marsh’s expedition, scientists are now more confident about what they are looking when they have the remains of an Ichthyornis disparon the table.

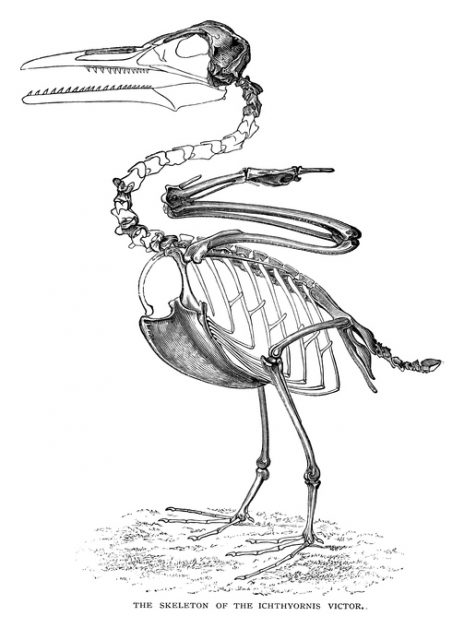

Ichthyornis Skeleton – Scanned 1886 Engraving

This toothed seabird was a transitional species that links modern-day birds with dinosaurs on the family tree. The Cretaceous period is an exciting era for evolution, when birds were undergoing a process in which many of their dinosaur traits were slowly but surely getting replaced with features we commonly see on their winged bodies today.

Experts from Yale University led the entire effort, and the findings of the CT-scan analysis and the subsequent digital reconstruction were revealed in the journal Nature on May 2, 2018. Of skulls used for the effort, three have been stored for years in different museums across North America, without undergoing stricter inspection.

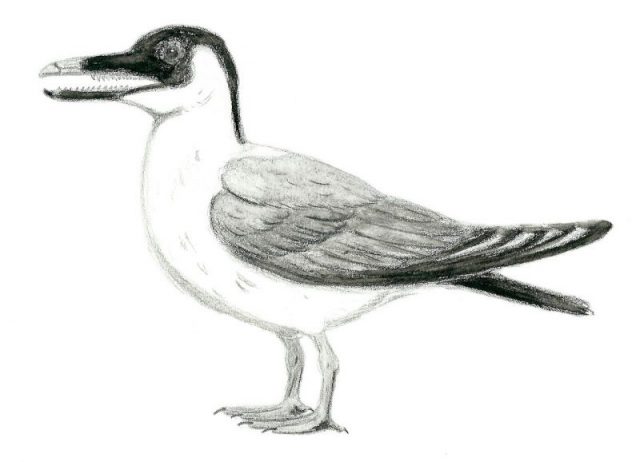

Life restoration of Ichthyornis dispar, a primitive seabird that lived in the Western Interior Seaway (North America) Photo: El fosilmaníaco – CC BY-SA 4.0

The fourth specimen, which actually propelled forward research on the ancient bird, was discovered in 2014, again in Kansas, by undergraduate Kris Super from Fort Hays State University, the National Geographic reports. This one was found embedded in rock and was dated to roughly 87 million years ago. There was no doubt the almost complete cranium was an extraordinary fossil, hence photos of it were forwarded to scientists at Yale University.

There, a Geology and Geophysics Assistant Professor, Bhart-Anjan Bhullar, and his team considered a different approach of how to examine the new fossil. Instead of extracting it from the rock in which it was stuck, the Yale scientists scanned it using computerized tomography. The research proceeded further, and more cranial remains attributed to the Cretaceous bird were examined and scanned in the labs. Among other things, it was recognized that the 1870s specimen included two important bones that had been overlooked in previous analysis.

Scientists used the scan results to finally produce a viable 3-D model of the Ichthyornis dispar skull, and suddenly they were looking at the first complete skull picture of this early relative of modern-day birds. Its jaw was filled with acute and arched teeth, much in the same manner as can be seen among dinosaur relatives, comparable to a degree with the jaw of a fierce Velociraptor, as some commentaries by experts tell.

The results also changed some of the old assumptions, that the upper jaw was fixed among early birds. On the contrary, both the top and bottom parts of it were able to freely move on their own.

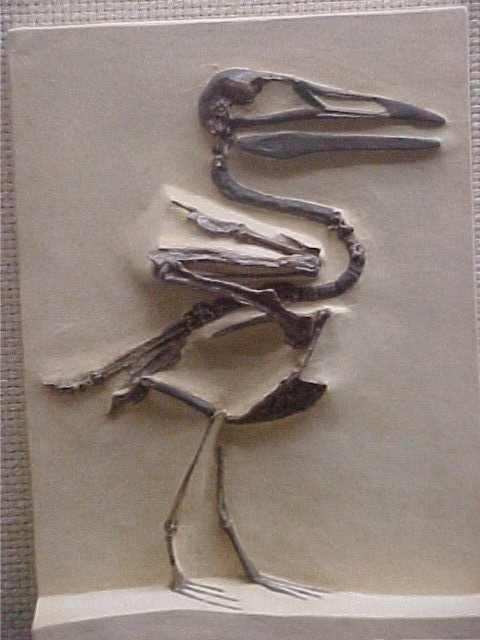

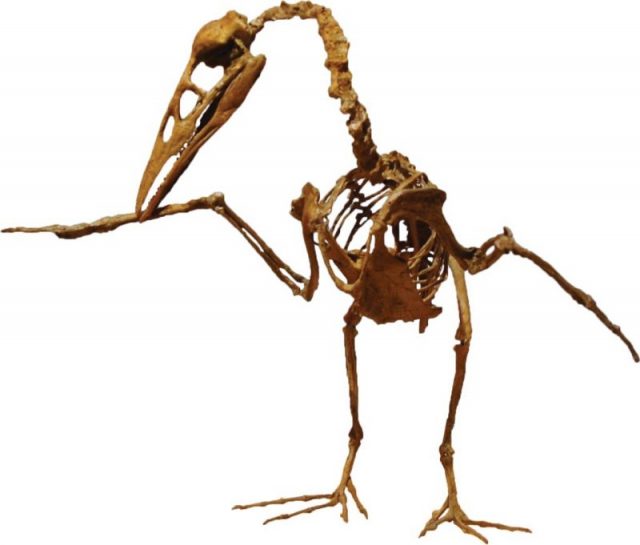

Cast of the original composite panel mount of “I. victor” (now I. dispar), Peabody Museum of Natural History. Photo: Greygirlbeast –

CC BY-SA 3.0

“Right under our noses this whole time was an amazing transitional bird,” said Yale’s Bhart-Anjan Bhullar in a statement. “It has a modern-looking brain along with a remarkably dinosaurian jaw muscle configuration.”

According to Bhullar, one of the most interesting aspects of all is that Ichthyornis disparreveals to us what the beak of birds looked when it first appeared during evolution, that it “was a horn-covered pincer tip at the end of the jaw.”

“At its origin, the beak was a precision grasping mechanism that served as a surrogate hand as the hands transformed into wings,” Bhullar says. Which means the bird likely used its beak just to collect fish or other seafood from the waters, only to then toss the catch into its scary, teeth-filled mouth.

Cast skeleton of Ichthyornis dispar produced by Triebold Paleontology, Inc. and displayed in the Rocky Mountain Dinosaur Resource Center Photo: MCDinosaurhunter – CC BY-SA 3.0

The latest finds have been praised by paleontologists and experts worldwide. Among them is Dr. Stephen Brusatte of the University of Edinburgh, who was not part of this effort but has recently led research concerning dinosaur footprint finds which were recently identified on Scotland’s Isle of Skye. Brusatte has commended the research as exceptional in statements for the Guardian, comparing Ichthyornis dispar to having “Frankenstein creature heads,” and theorizing that this outlook would have been the product of an extensive evolutionary period.

Although nearly a hundred other specimens of Ichthyornis fossils have been found, only this latest research has allowed the establishment of a more scientifically accurate narrative. Most of the other fossils, a great many reportedly found in China, have been in poor condition. Compressed almost flat, these fossils have not let anyone envision the shape of the head of the species.

In addition to having a complete picture of the ancient bird’s head, experts have been able to confirm other details–for instance, that beaks were out there in nature earlier than thought before, likely around the same period when birds began sprouting their wings.