May 18, 2018 E.L. Hamilton

A group of ethnic-minority villagers in one of the poorest corners of China have steadfastly refused to give up the place they have called home for a decade, a half a century, or even thousands of years, depending on whom you ask. Their castle is an enormous cave.

If Ethnic Miao have hidden in the massive cave in Guizhou, in southwestern China, for thousands of years and have stayed there ever since, it would make it the last and longest continuously inhabited cave in the country, if not the world. (Some dispute this claim, saying the Miao came in 1949, during the Cultural Revolution.) The cave is surrounded by spectacular limestone peaks and lush emerald-green forests.

But what is most impressive is its massive size: Zhong Cave, a limestone cavern, is big enough to hold four football fields. It is 160 feet high. In photographs, the cavern is so huge that the bamboo-and-wood structures inside look like dollhouses. Smaller upper and lower caves frame it; both are not big enough for habitation. The village’s name, Zhongdong, means “middle cave.”

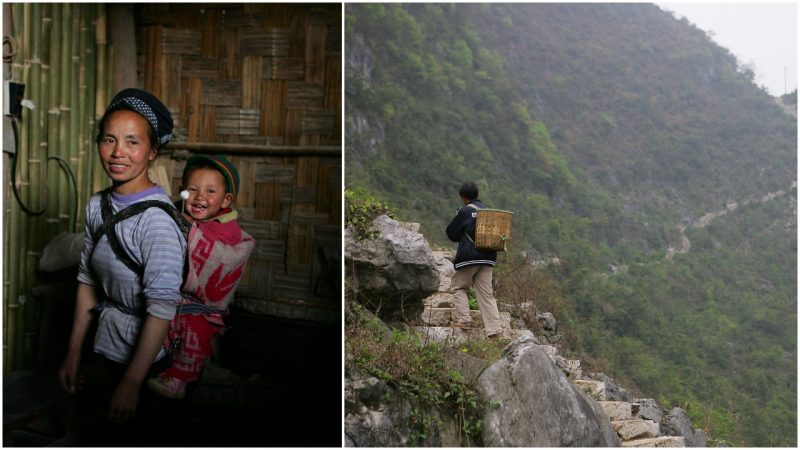

A villager walks from the Middle Cave, home to a community and school, to town on the weekly market day (Photo by Cancan Chu/Getty Images)

The cave is in the region of Getu River National Park, an area of mountains carved up by winds and rain. It is a remote place in a remote region. Getting in or out requires a one-hour hike through a treacherous rock-strewn valley pass; from there it’s a bumpy four-hour drive to the nearest town. Recently, it has become something of a tourist destination, which benefits the residents hugely. Locals rent out rooms to adventurous visitors who’ve come to gawk at the cave and take photos for Instagram.

(Photo by Cancan Chu/Getty Images)

As happens in many remote areas, children leave the cave during the week and board at school for education; they return home on weekends, when the cave fills with the sound of their laughter. During the week, the sounds of cows, pigs, and chickens echo off the walls. Below the cave, terraced fields allow farmers to grow millet and vegetables on which to subsist. Water is collected in cisterns. The woven bamboo houses don’t have roofs—because they don’t need them, as the cave provides the shelter.

Electricity came to the cave dwellers only in 2002, introduced by a visiting American businessman and philanthropist who became enchanted by the setting. He also set up funding for a communal bathroom and a schoolhouse; the latter was closed in 2011, and children sent to a boarding school two hours away.

(Photo by Cancan Chu/Getty Images)

Local officials have taken an interest in the cave’s tourism potential and want to relocate the residents to a block of white-walled farmhouses constructed about a decade ago in the valley below. The government offered residents 60,000 renminbi, or about $9,500, in relocation fees, according to the New York Times. Five families have accepted; 18 have refused to leave. They don’t want to lose their land or their historical connection to the cave. They wish to stay in control of the small but growing tourism income. (A cable car to the cave envisioned by an enterprising entrepreneur was started but never finished; its rusted terminus sits eerily atop the mountain.)

It’s not the first time the government has tried to coerce the cave dwellers to abandon their natural shelter. But stubborn residents always hold on to the hope of staying there, even if life isn’t perfect in a dark and dank cave.

A villager and her son pose in the MIddle Cave, home to a community Photo by Cancan Chu/Getty Images)

As many as 200 people have lived in the cave, but many young leave in search of jobs and a better life. Those who stay are fortunate to make a couple of hundred dollars a year.

Living in a massive cave isn’t that preposterous of an idea in a country of resourceful but impoverished farmers. In other parts of China, locals have carved cave dwellings in the side of hills or deep in the ground. The earthen homes are naturally warm in the winter and cool in the summer. But the Zhong cave stands out for being the only inhabited cave in China tall enough to accommodate two- and three-story structures inside its porous walls, with plenty of clearance.

Many residents of the cave are elderly, don’t speak Mandarin, and fear isolation if they were forced to leave their tight-knit cave community. Wang Qiguo, a hostel owner and the head of the village, explained their resistance to moving to the Times: “The residents of this cave should be the administrators of tourism here, regardless of whether or not we are paid.”