Exploration is a concept that holds a special place in the mind. We are driven by the wish to explore, to know the unknown. Even today, we need to find out many things about our planet; we are still missing pieces of the enormous puzzle called knowledge. At the same time we are embarking on a different journey, a journey that will take us to the stars. It’s a new “unknown” that makes the game of discovery interesting again. If we look back, it’s not wrong to say that the Ancient Greeks were in a similar position.

During the Golden Age of the Ancient Greek Empire (500-350 B.C.), Hellenic culture was at its peak. Every element of society bloomed. The people decided to take a different perspective on the world and set the foundations of modern philosophy, science, politics, and art. They also did one more important thing. They started expanding, either by trade or by war, and thus the Ancient Greeks created their first colonies across the Mediterranean.

The thirst for more riches, mixed with curiosity, shaped the first explorers–the ones who would become the archetype for people like Roald Amundsen or Captain Scott. Ancient Greek sailors started venturing farther than the Mediterranean, out of those well-known waters and into the fog of territories that they had only heard of in their mythical stories, or the speeches or writings of the contemporary philosophers and historians. Imagine them navigating their ships farther north or south than any of their compatriots, unsure whether they would encounter other men, or gods, or mythical creatures. Most important of all, they documented most of their adventures and places they visited in a type of manuscript called a periplus. One such ancient explorer was a successful trader and mariner called Pytheas, born in the Greek colony of Massalia (which is the city of Marseille today). Sometime about 325 B.C., Pytheas began a voyage that would lead him to the discovery of Britain, northwestern Europe, and even guide him as far as the Arctic Ocean.

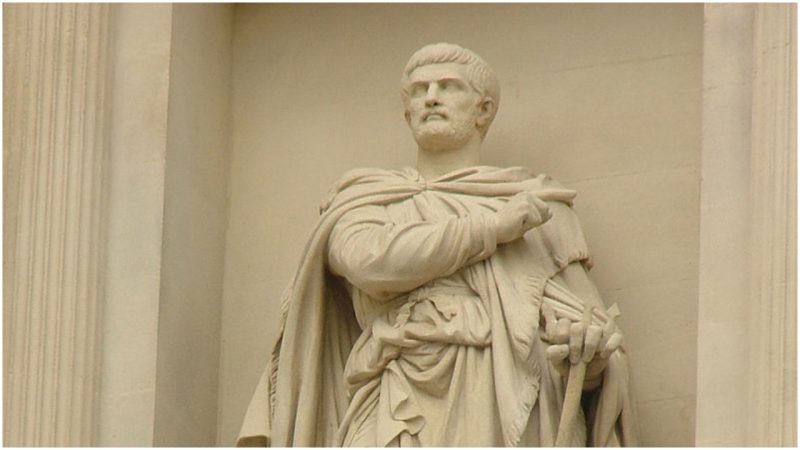

Statue of Pytheas outside the Palais de la Bourse, Marseilles.Author: CC BY-SA 3.0

Unfortunately, no written word survived from Pytheas, and we only know about his travels through excerpts and quotations from him in the works of later ancient authors such as Timaeus, Pliny, Strabo, or Diodorus of Sicily. According to the most widely accepted historical theory, all of the information about Pytheas’ journey was taken from his travelogue, which was probably called On the Ocean (Peri tou Okeanou). According to the experts, this was not a typical periplus; it was more personal, written with an artistic sense, and contained a broad spectrum of information (astronomical, geographic, biological, oceanographic, and ethnological), unlike a standard periplus, which was a more basic navigational report.

Although not everything is certain and factual about the journey of Pytheas, modern researchers have made an attempt to determine his actual trajectory of movement based on all the data that is available in the fragments. So where did he really go and which places did he visit?

The most accepted theory is that Pytheas started his journey from his home port of Massalia and from there he headed west through the Strait of Gibraltar (the passage was known back then as the Pillars of Hercules). When he reached the Atlantic, he sailed north along the coast of Spain and France. It is possible that at this point he landed at Brittany, in northwest France, for a short time. From there, he crossed the English Channel and arrived at a place he called “Belerion.” Most historians believe that this is modern-day Cornwall. The ancient writer Strabo mentions that Pytheas called the new land he discovered “Bretannike.” Diodorus of Sicily, on the other hand, uses the word “Pretannia” and he called its inhabitants Pretanni. Either way, this sounds a lot like Britain.

If we take these writings as fact, Pytheas became the first Ancient Greek traveler to discover Britain. In his lost manuscript he described life in the new land he visited. According to the fragments, the British mined tin and traded it to Gaul, sending the tin to the Mediterranean eventually. He observed that the people of Britain lived in thatched cottages and stored their grain reserves in underground silos. He also explained that the British people were ruled by many kings, and they were not fighting each other. Furthermore, Pytheas gave a geographical description of Britain. He mentioned that opposite continental Europe is the province of Kantion (Kent). Several days’ travel from Kantion was the province of Belerion (which is almost definitely Cornwall). The third place in Britain he mentioned is Orkas (probably the biggest of the Orkney Islands). This looks like a description of three different points in Great Britain, which could mean that Pytheas circumnavigated the British Isles. Even if this is not true, he was the first foreigner that gave a written description of Britain at the time.

Thule archaeological site. Author: Ansgar Walk CC BY-SA 2.5

This was not the end of Pytheas’ explorations. After he finished sailing around Britain, his journey took a mythical twist. It is believed that Pytheas continued sailing north and entered the North Sea. During this part of his epic journey, he claimed that he discovered Thule–a mythical and hypothesized piece of land that according to scholars of the time (and even in the Middle Ages) lay at the edge of the world. In other words, Pytheas claimed that he reached the end of the world. Today, these are two theories of what Pytheas’ Thule might have been in reality. Some scholars think that Thule is actually Iceland, while others think it is somewhere in Norway.

One thing is for sure–Pytheas described a phenomenon that wasn’t part of the experience of someone who lived his whole life in the Mediterranean. He wrote that at Thule there is no night during the summer solstice. This could only mean that Pytheas reached the Arctic Circle, but where exactly?

Ancient authors mention that Pytheas reached Thule after sailing for six days north of Britain. They say that he began his voyage at an island called Berrice. It is possible that this is the Island of Lewis in the Scottish Outer Hebrides. If this is the case, Thule is probably somewhere close to modern-day Trondheim, Norway. Pytheas didn’t stop here. According to the fragments, Thule was a day’s sail from a frozen sea. (Ancient writers used the phrase pepeguia thalatta, which translates as “solidified sea.”) Many believe that this is a description of the Arctic Ocean. The surviving pieces of writing regarding this stretch of the journey are the most enigmatic. Ancient authors describe a place in which earth, water, and air exist as one substance. The speak of a so-called “sea-lung” in which all of these elements are held. According to scholars, there are two possible explanations for this. Pytheas either described a phenomenon that is known today as “pancake ice,” or spoke about jellyfish, which were also called “sea-lungs” (pleumon thalattios). If assumptions are correct, Pytheas could be considered the first Arctic explorer.

Stonehenge Closeup

On the way back, Pytrheas probably passed along the coast of ancient Germany, and allegedly met with the Gutones–a tribe that lived around a big estuary. It is also possible that he landed on the Island Heligoland, which is known to possess huge reserves of amber, a material of which the Ancient Greeks were very fond. Some historians even think that this whole trip was motivated by the idea of finding more sources of amber. Some of the theories about Pytheas’ travels claim that he went farther and sailed into the Baltic Sea, and even came to the Vistula River in modern-day Poland.

Whatever the truth may be, the story of Pytheas is inspirational. He might not be historical as much as he is legendary, but still, an explorer. One could only wish to read the original manuscript of this early European odyssey.