Fences are said to make good neighbors. This was especially true on the American frontier in the late 1880s when people talked literally over the wires. It all came about when Alexander Graham Bell’s invention of the telephone collided with the epic fencing of the Great Plains.

In 1874, the invention of barbed wire was a noted success for its intended purpose: it provided low-cost fencing in the Great Plains to solve the pesky problem of separating ranchers’ pastures from farmers’ fields. The use of barbed-wire fencing spread so rapidly that sales went from 10,000 pounds in 1874 to 80.5 million pounds in 1880, according to a report by University of Maryland history professor David B. Sicilia, traversing acres of sparesly populated territory.

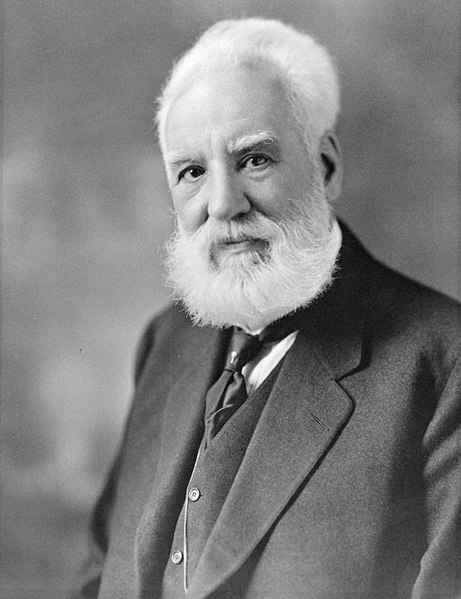

Meanwhile, in Boston, Alexander Graham Bell was famously and feverishly working to transmit sound over wires. On March 10, 1876, he secured possibly the most valuable patent ever, for “transmitting vocal or other sounds telegraphically” (which also resulted in years of legal hassles from competitors). Just three days later, Bell successfully if inadvertently made his first “call” to his assistant in the room adjoining his laboratory, speaking the memorable sentence all schoolchildren can now recite: “Mr. Watson! Come here, I want to see you.”

Alexander Graham Bell

The ensuing telephone boom concentrated unsurprisingly on urban areas: Densely populated cities required less infrastructure to connect people. Urbane snobbishness may have played a role as well: country folk were considered too unsophisticated to appreciate the phone, according to Sicilia.

This was an oversight: It was probably more practical for far-flung farmers to connect on the telephone than it was for city dwellers, who could lean out a window to call a neighbor and who measured distance by city blocks not miles of acreage.

Bell placing the first New York to Chicago telephone call in 1892

With a phone, farmers and ranchers could get weather reports, recruit help, price crops, and generally deal with countless crises. So they banded together to form crude early networks, called “mutuals,” linking together a few farms via a switchboard in a kitchen or store or on a community party line. (Party lines existed in rural areas well into the 1950s. People who picked up their phones to make a call and heard someone else’s conversation were supposed to politely put the phone back down and wait their turn.)

With ingenuity common in pioneering America—when much had to be made from little—the farmers and ranchers quickly figured out an inexpensive way to wire their network: through the barbed-wire fencing strung across the Plains. Insulators to protect the wire were made from whatever was handy, and included corn cobs, worn-out boots, bits of tire, the necks of broken whiskey bottles. Farmers ran wires into their homes via porcelain tubes and talked on Sears phones. One handy rancher in Montana even installed knife switches at regular intervals for circuit troubleshooting, according to Inc. magazine.

Rules of civility governed the social network: Each house had a distinctive ring, a combination of short or long rings, as well as a ring that applied for everyone, in case of emergency. You were trusted not to listen in on other people’s conversations, unless you were invited to join in the sharing of news of the day.

Retro red telephone

“People would read the newspaper over the telephone,” historian Rob MacDougall told Inc. magazine. “They’d have musical nights where someone would play their banjo, someone else would sing along, and others would listen.”

At its peak, these DIY independent telephone networks supposedly included 3 million people, more than the official Bell system. And phone use did prove more valuable to farmers. By 1912 more farm households than nonfarm households had telephones, and in 1924 Iowa led the nation in telephones per capita, according to Sicilia.

By the 1920s, formal companies installed regular phone wires across the country, but some rogue frontierspeople, attracted by the no-cost fee, continued using the barbed-wire lines until the 1970s.