Charles Darwin is the father of evolution science and a biologist whose studies set a milestone in explaining the origins of all living forms on Earth.

His theory of natural selection turned the 19th century science world upside-down and has been a subject of lively debate and numerous studies ever since.

Although Darwin’s academic carrier continues to interest scholars around the world, the biologist’s personal life is actually rather puzzling.

Darwin, the father of evolution–and genetics for that matter–decided to marry his first cousin, with whom he had 10 children, some of whom seem to have exhibited direct symptoms of inbreeding.

Charles Darwin and Emma Wedgwood, who was the daughter of his mother’s brother, tied the knot on January 29, 1839.

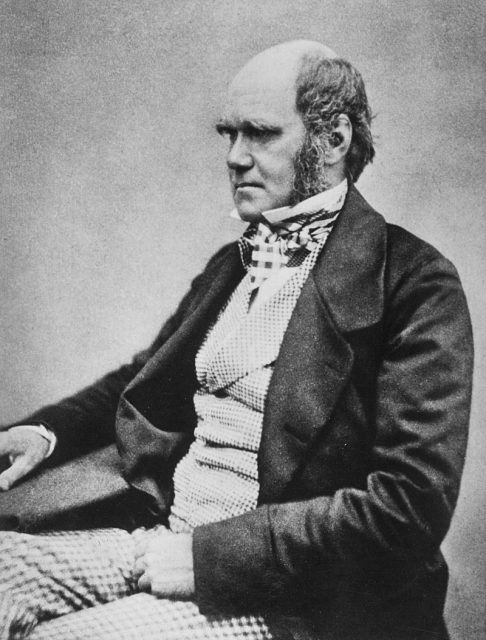

Darwin, c. 1854

While first-cousin marriage seems like a social taboo today, put in wider historical context, it was quite common, especially among royalty and aristocrats.

From the members of Egyptian dynasties to the Hapsburgs of the Austria-Hungarian Empire, marriage within the family group was a means of keeping the power and wealth within a trusted circle.

In Victorian England, closely-knit families perceived marriage as more of a business deal than a quest for love. Nevertheless, the consequences were apparent―high infant mortality rates, various defects and mental illnesses, all of which were more frequent among children conceived in incestuous relationships.

As for the Darwin–Wedgwood family, their alliance goes back to the 18th century.

Doctor Erasmus Darwin, who was a successful physician, poet, inventor, and a slave-trade abolitionist, and Josiah Wedgwood, founder of the pottery company Josiah Wedgwood and Sons, both saw opportunity in joining together and expanding their wealth and influence. Since that time, several members of the two families got married, which later led to inbreeding.

According to an international team of American and Spanish scientists that established the genealogy for four generations of both the Darwins and Wedgwoods, Darwin’s mother and grandfather were both Wedgwoods, and his mother’s parents were third cousins.

Darwin chose to marry his cousin, Emma Wedgwood.

Back then people were not as aware of the dangers of inbreeding. Simply put, the result of mating between two individuals who share much genetic material could cause harmful recessive traits to overcome the healthy genes. Thus, “bad genes” have a greater chance to prevail, manifesting themselves in an array of physical defects or lack of immunity to disease.

Despite the fact that such consequences were already known within the scientific community, including Darwin, the famous biologist decided to take his chances.

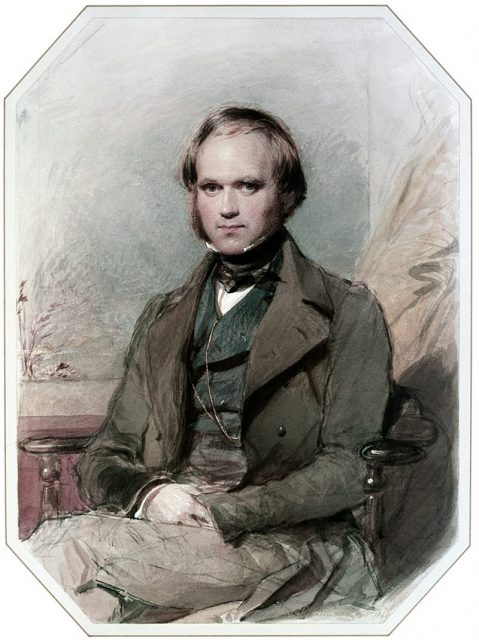

Water-color of Emma Darwin, 1840, by George Richmond (1809-1896)

Emma, the grandson of Josiah Wedgewood, wasn’t aware at first that Charles was interested in marrying her. After all, they were cousins, albeit ones whose families had a history of joining together in matrimony.

Despite her lack of expectation, a short period of courtship and a wedding proposal followed.

Darwin was by that time immersed in his studies, and may have feared that starting his own family might be an obstacle in his path to achieving greatness.

He worked long hours, rarely resting. His body just couldn’t handle his mind’s unstoppable drive.

The scientist started suffering from various illnesses―all of which were mostly misunderstood by the physicians of his time.

Charles Darwin by G. Richmond

Darwin was plagued by a number of symptoms, including headaches, tremors, vomiting, stomach aches, and tachycardia to name a few, but the doctors never agreed on a precise diagnosis. Even today, the matter of Darwin’s health is a subject of discussion.

Just prior to the proposal he made a sort of a pros-and-cons list, with one column titled To Marry, and the other Not to Marry. For Darwin, marriage seemed like a dull formality, for he wrote in the anti-marriage section that a spouse would mean “less money for books” and a “terrible loss of time.”

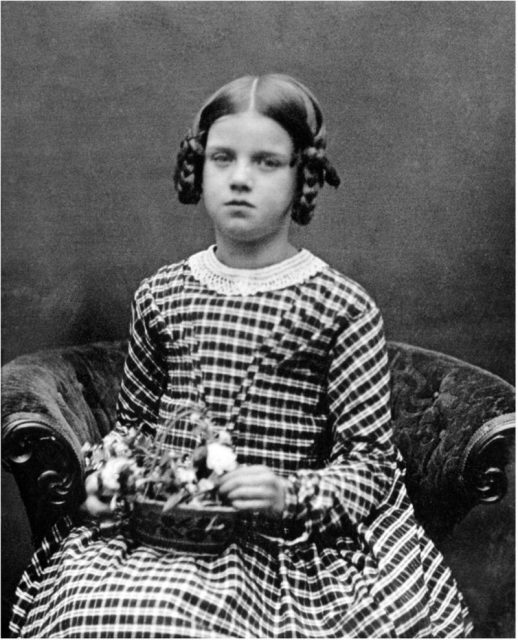

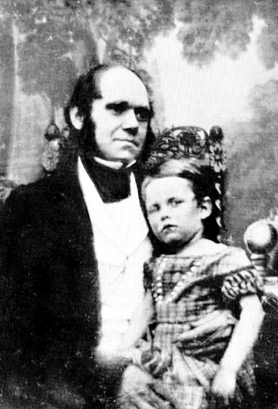

Emma with son Leonard, 1853

On the other hand, he reportedly noted that a “constant companion and a friend in old age” was “better than a dog anyhow.”

Despite such terminology, the two formed a deep and loving relationship in time, and stayed together until the day he died, 43 years after the ceremony.

In 1839, their first son, William Erasmus, was born. In the period between 1841 to 1856, the other nine children were brought into this world.

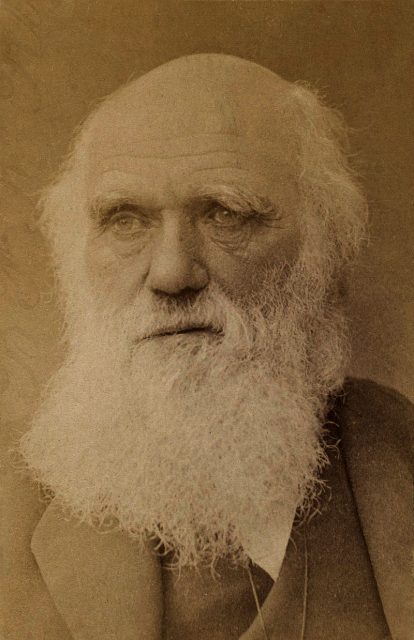

Charles Darwin, photograph c. 1881

After settling in London, Charles and Emma decided to move to the more rural setting of Downe, in the London borough of Bromley, as they considered it a good place for raising children. But not all of their children would reach adulthood.

Anne, born in 1841, contracted tuberculosis and died at the tender age of 10. Her sister Mary, born in 1842, died only a few weeks after birth.

Annie Darwin. Her father was devastated when she died in 1851.

Their youngest child, Charles Waring Darwin, lived for only two years. While this was not an unusual statistic for the era–childhood mortality rates were much higher than today–Darwin, an educated biologist, was aware of the potential consequences of inbreeding from his own studies and experiments.

He personally monitored all the health issues his children encountered as they grew up and kept a notebook which later served both as testimony and as the basis for future research.

During the Darwin family’s 1868 holiday in her Isle of Wight cottage, Julia Margaret Cameron took portraits showing the bushy beard Darwin grew between 1862 and 1866.

It is documented from a letter he sent to one of his friends that he considered the children to be weak-looking, or in his own words―”they are not very robust.”

Three of them suffered from infertility, a trait that could be connected to inbreeding. Darwin noted that they were all sensitive and prone to various sicknesses, although showing no signs of permanent physical or intellectual disability.

Charles and William Darwin

Quite the contrary, in fact, three of his sons―George, Francis, and Horace―became respected figures in their fields of interest and were even knighted.

Tim M. Berra, the author of Darwin and His Children: His Other Legacy, relied on these notes when he decided to thoroughly study Darwin’s offspring and their medical conditions, in an attempt to shed light on the scientist’s family.

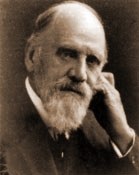

Francis Darwin, his scientist son

Berra concluded, by studying 25 nuclear families across four generations of Darwins and Wedgwoods, that the autosomal genomes of Darwin’s children were more than 6 percent identical, or homozygous.

This is four times the amount of overlap compared just to children of second cousins.

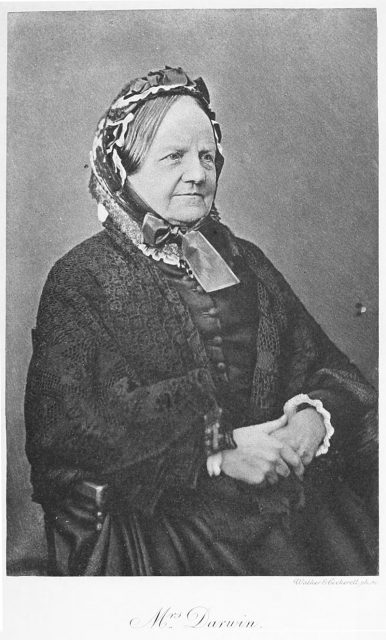

Emma Darwin in older age

Thus, the man who set the founding stone for genetics became a victim of his own field of research. However, the studies he conducted while observing his children did help him develop rather advanced theories about the dangers of inbreeding.

He even wrote to parliamentarian John Lubbock in 1870 about his concerns, claiming that “consanguineous marriages lead to deafness & dumbness, blindness [etc.].”

Charles Galton Darwin, the grandson of Charles Darwin.

Darwin proposed that questions be included in England’s census concerning such issues, so he could gain broad population-based data on the frequency of inbreeding in the country, as well as effects it has on the children.

Unfortunately, his proposal was dismissed, but today we can certainly confirm that this progressive initiative could have influenced many in preventing genetic mutations.