“To laugh often and much; to win the respect of intelligent people and the affection of children…To know even one life has breathed easier because you have lived. This is to have succeeded!” — Ralph Waldo Emerson

If we take that as an actual measurement for success, an author from a small village in New York State could be regarded as one of the most successful individuals in history. He won the respect of millions and the hearts of every child. He made us laugh. He made us cry. He made us realize that in the end “a heart is not judged by how much you love, but by how much you are loved by others.”

Well, L. Frank Baum is loved by almost everyone. Could it be because he made our lives easier?

Baum was a fragile child who lived through a heart attack in his adolescence when his parents attempt to toughen him up by transferring him to a military academy. He was not a strong child, physically speaking, but he was never down-spirited, nor was he short of imagination. For as long as he could remember, Baum saw things differently than most, or at least he wished things to be different.

As a farmer’s boy, he always imagined the scarecrows on his family’s estate were about to come to life.

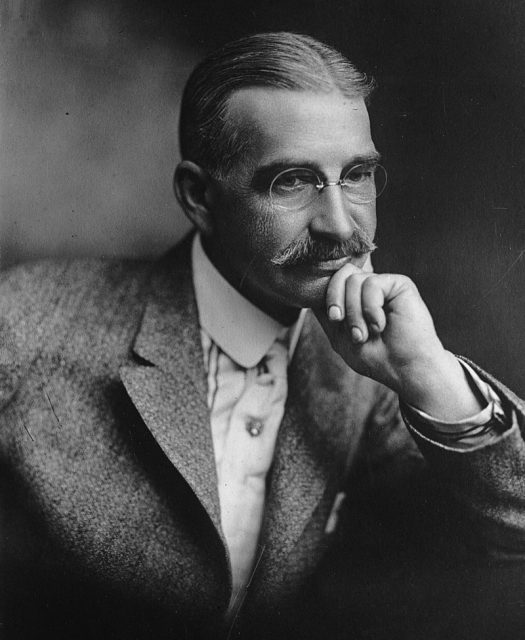

L. Frank Baum (1911)

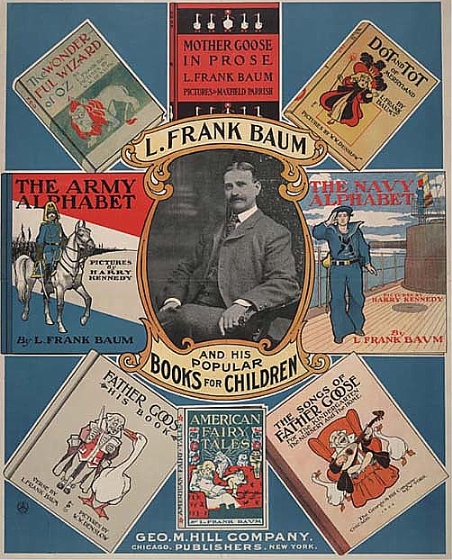

In his teens, Baum produced a journal and pamphlet about stamp collecting. He was a prolific writer throughout his life, penning 55 novels, 83 short stories, countless poems, and more than 40 play scripts, and he contributed to various newspapers and journals. He even founded The Show Window magazine in 1897, the precursor to Visual Merchandising and Store Design magazine, which is still in production today. Baum had a varied career, publishing his first book, The Book of the Hamburgs: A Brief Treatise upon the Mating, Rearing, and Management of the Different Varieties of Hamburgs, in 1886 while trying his hand at poultry breeding.

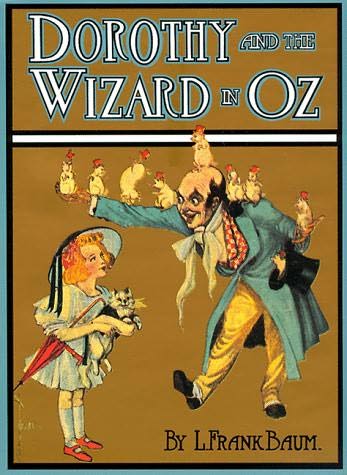

The original 1908 cover to Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz

Mother Goose in Prose was Baum’s first children’s book, and it proved to be successful enough that he could give up his job as a traveling salesman. Two years later, Father Goose, His Book, made him the bestselling children’s author of the year in the United States. And when in 1899 he finished the last sentence in the manuscript of a book originally titled “The Emerald City,” he must have felt that he was finally doing what he was supposed to. He must have felt pride in his achievement, for he had his pencil framed and hung on the wall over the desk in his study. He knew he had written something of merit. He wasn’t fully aware how worthy it was though.

“Then there is the other book, the best thing I have written they tell me,” he wrote to his brother, Harry, right before it was originally published in Chicago on May 17, 1900. “Mr. Hill, the publisher, says he expects a sale of at least a quarter of a million copies,” reports the Chicago Tribune.

The book sold like hotcakes.

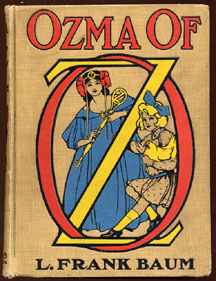

The original 1907 cover to Ozma of Oz.

Renamed The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, and illustrated by W. W. Denslow, it was a hit. According to the publishers and the author’s representatives, the first printing of 10,000 copies was sold out within a fortnight. The next, 15,000, took only 10 days. By the end of January 1901, about 90,000 copies had been sold. The book was breaking record sales and remained a bestseller for two years. He no longer needed to dream of scarecrows coming alive. By the end of 1956, when it entered the public domain and could be freely reproduced, Dorothy, the book’s heroine, blown by a real Kansas tornado to the land of Oz, found her way back home in at least three million homes in America.

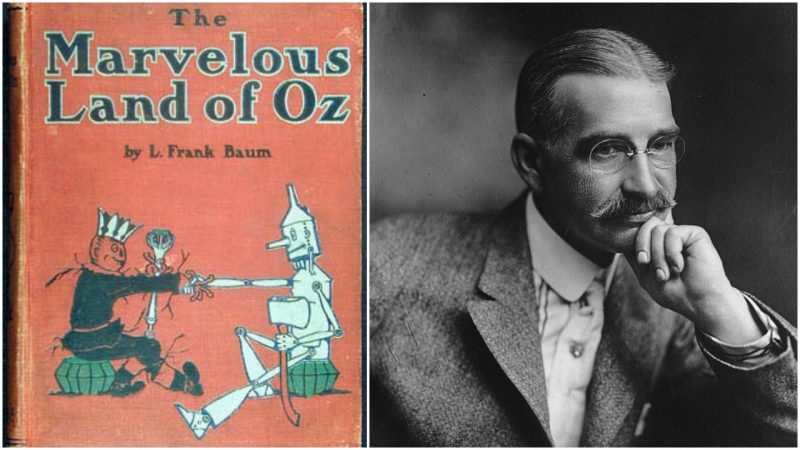

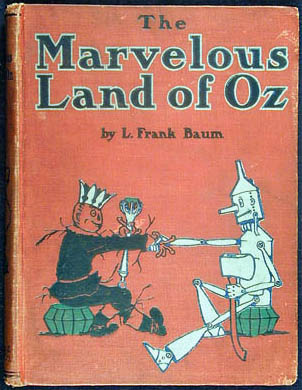

Book cover of The Marvelous Land of Oz (1st edition), published in 1904.

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was something new. It was the first real American fairy tale for little boys and girls. Nothing like previous Grimm-like cautionary tales aimed to scare children. Braum would never write such a tale. In fact, he despised the horrors in fairy tales commonly read to children. He wished to give them horror-free fiction.

Baum wrote a lovely tale about imperfection, one of universal importance with lovable characters that have such profound meaning behind their seemingly silly exterior, designed specifically for those dark times when we think less about our abilities and think little of ourselves. It’s about when we think we don’t have what it takes to act upon certain things or believe we are not smart enough to overcome them. He wrote a story not to scare kids, but to prepare them for life ahead and to teach about the true meaning of compassion and free their minds. To teach them that they have to care for one another and to respect each other and help each other.

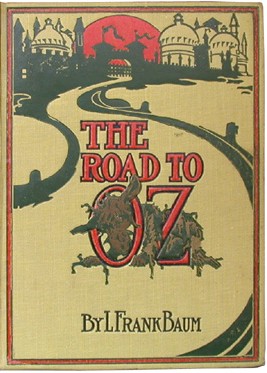

The Road to Oz 1st edition front cover.

A lion was whining for courage. A “mindless” scarecrow was searching for a brain. And a rusty old Tin Woodsman believed he had no heart. His story had three sidekicks who were all missing and craving those things they believed were lacking. Nevertheless, they helped a little girl find her way home and breathe easier along the way. She helped them feel complete.

And the young ones? Well, they couldn’t get enough of it. Thousands of letters written by the youngest of fans arrived at Baum’s doorsteps and the offices of George M. Hill Company, his publisher. They were begging for more of Oz, more of Dorothy, more about the Lion and the Tin Man and Scarecrow. They were craving love and courage.

Promotional Poster for Baum’s “Popular Books For Children”, circa 1901.

And he delivered. Baum wished to write something else and felt the story was well-rounded with how it ended. But having endured a hindered childhood himself, the author knew more than anyone how it was to be craving things. By July 1904, to everyone’s delight, he released The Marvelous Land of Oz. It was the first sequel to The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, followed by the Ozma of Oz in 1907 and Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz the year after. The Road to Oz arrived sooner than expected in 1909 and The Emerald City of Oz within a year. The 1902 stage production of The Wizard of Oz was also fairly successful, touring with its original cast until 1911.

So he continued on his own “yellow brick road,” ultimately leaving behind a legacy of one marvelous story expanded with 13 nothing short of spectacular sequels to the world when he died in 1919.

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, declared “America’s greatest and best-loved homegrown fairy-tale” by the Library of Congress, has been translated in almost 50 languages and is considered to be the most-read children’s book in the world.

On the first page of a copy of Mother Goose in Prose that he gave to his sister, Mary Louise Brewster, Baum wrote: “To please a child is a sweet and a lovely thing that warms one’s heart and brings its own reward.” He would later explain it’s what drove him to write children stories and kept him going throughout his illustrious career.

It is strange and moving how one man’s few words on success when seen through another man’s legacy can prove to be words worthy enough to live by.