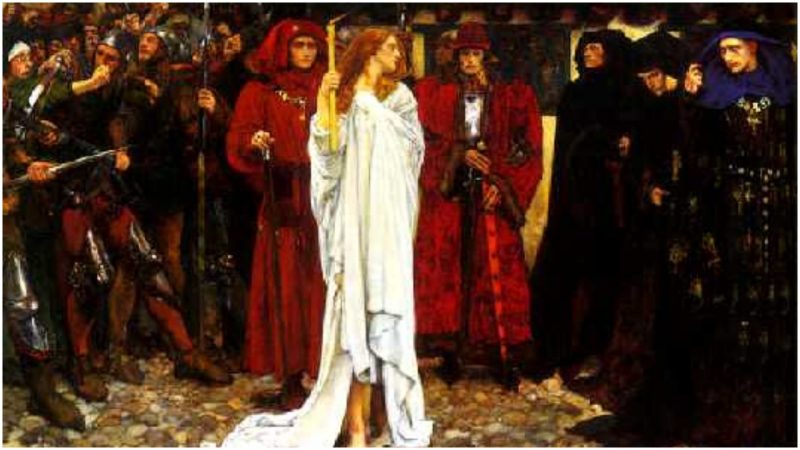

On November 13th, 1441, the curious people of London lined the streets to observe an act of public penance. The criminal was a woman, perhaps 40 years of age, bare-headed, plainly dressed, who was rowed in a barge to Temple Stairs off the Thames. She would then proceed to walk all the way to St. Paul’s Cathedral, carrying before her a wax taper of two pounds and showing the entire time a “meek and demure countenance.”

She was no ordinary woman and hers was no ordinary crime. The condemned woman was Eleanor Cobham, the wife to a royal prince: Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, only surviving uncle to the childless Henry VI and the the heir to the throne. The duchess had been tried and condemned for heresy and witchcraft. This was the first of three days of ordered pilgrimages to churches. Afterward, she would be forced to separate from her husband and live in prison for the rest of her life.

The downfall of Eleanor Cobham was a shocking event in the 15th century, and it’s disturbing today. Certain elements of her life echo Katherine Swynford’s, the longtime mistress of John of Gaunt who eventually became his third wife. A bold beauty manages to marry a royal–it was seen again, and much more famously, in the following centuries with Elizabeth Woodville and Anne Boleyn. But while rumors of witchcraft swirled around both of those queens, the accusations were, historians now agree, not based in reality. While Eleanor Cobham most probably did dabble in the black arts. The most serious of such crimes was to seek to know–or perhaps even alter–the future, through the practice of necromancy.

Ever since the age of Homer, necromancers have hovered in the darkest shadows of society. They were believed to possess the secrets to unlocking the power of the underworld to divine the future. No matter the results—or lack thereof—necromancers did a brisk business in the Greek and Roman world. It was only by following their secret and ornate rituals, they said, could the boundaries be dissolved between the living and the dead.

Eleanor Cobham performing penance for her admittance of involvement in a conspiracy to kill Henry VI.

After Rome fell, the early popes struggled to extinguish the pagan practices of not only necromancy but witchcraft, astrology, and alchemy. But these practices survived through the Middle Ages, in one form or another, and in the Renaissance, as scholars pored through ancient texts, experienced a rebirth. Some popes even employed their own astrologers. The Munich Manual of Demonic Magic, a textbook in Latin, was compiled in the 15th century. Necromancy became, if anything, more common. After drawing a series of magic circles, saying conjurings, and making sacrifices, necromancers claimed a demon would appear to assist: see the future, drive a man to love or hatred, discern where secret things were hidden, such as treasure.

During the 15th century, England was a kingdom of devout Catholics–and yet superstition ran amok. In 1456, 12 men petitioned Henry VI for permission to practice alchemy, among them two of the king’s own physicians. Some courtiers owned astrological books. What was heresy and what was knowledge linked to the fashionable pursuit of ancient texts? It was hard to know what was forbidden–until you made a mistake. And then you could lose your life.

The stage was set for Eleanor Cobham and her ambitious play for love, power, and glory.

The daughter of Sir Reginald Cobham, Eleanor in her early twenties entered the service of the illustrious Jacqueline, Countess of Hanault. Jacqueline repudiated her husband, John of Brabant, and fled to England in search of champions, marrying the youngest brother of Henry V: Humphrey, duke of Gloucester.

At some point over the next five years, Eleanor herself became the mistress of the duke, the husband of her employer. Humphrey abandoned his wife; the pope annulled the marriage because of legalities to do with her first husband. Humphrey married her lady in waiting, Eleanor.

Illuminated miniature of Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, and his second wife Eleanor, Duchess of Gloucester, from the Liber Benefactorum of St Albans by Thomas Walsingham, Cotton MS Nero D VII, British Library

His nickname of “Good Duke Humphrey” notwithstanding, Gloucester was a complex man. Well educated, he supported learning more than most aristocrats and was a devoted patron of the arts. An enthusiastic soldier, he was devoted to his oldest brother, the famous warrior Henry V. But Humphrey was also impulsive and vengeful. There is little doubt he was, in addition, a womanizer. After the death of his brother the king, he claimed the right to be regent for his infant nephew. His claims were supported in the dead king’s will. But Cardinal Henry Beaufort and the rest of the Beauforts opposed Gloucester. The two branches of the Lancaster family fought for power for the rest of Humphrey’s life.

Eleanor did not make Humphrey more popular. She was criticized for her immoral history and for her greed. Historian Ralph Griffiths says, “One chronicler noted how she flaunted her pride and her position by riding through the streets of London, glitteringly dressed.”

The unmarried Henry VI, passive and easily led, was fond of his aunt and uncle. Historians believe a decision was made in the Beaufort camp to permanently weaken the duke of Gloucester, and the key to the attack was his wife.

In late June 1441, word spread through London that two men had been arrested for conspiring against the king–divining the king’s future through the use of necromancy and concluding that he would soon suffer a serious illness. The accused were two clerks, Roger Bolingbroke, an Oxford priest, and Thomas Southwell, a canon. (Those who practiced necromancy were often low-level clericals, because they possessed the knowledge of Latin necessary to read forbidden books and learn the rites.)

The conjuration from Henry VI (Act 1, Scene 4)

The men were sent to the Tower of London and possibly tortured. Bolingbroke told his interrogators that he had been prompted to look into the future of the king by the duchess of Gloucester.

Eleanor did not behave like someone innocent of all crime. She fled to Westminster, seeking sanctuary. Later, when she was set to appear before an ecclesiastical court, she tried to escape onto the Thames river, but she was caught. A witch was produced, Marjorie Jourdemayne, who said she procured love potions for the duchess to make Gloucester marry her. In her trial, Eleanor denied seeking to know the future of the king through necromancy, but she “did acknowledge recourse to the Black Art.” It is believed she turned to the necromancers and witch to try to bear a child.

Eleanor’s co-conspirators were condemned and executed–Margaret Jourdemayne was burned at Smithfield. One of the clerks was hanged, drawn, and quartered. Eleanor spent the rest of her life confined in various castles. She died in 1452. Her husband Humphrey, who, to the puzzlement of many, had done little publicly to free her—he “said little”—died five years before Eleanor. His wife’s disgrace had finished him as an important man of the kingdom.

Did Eleanor turn to the dark arts to try to bring about the death of Henry VI so that her husband could become king and she become queen? Most historians doubt she went that far; more likely, she dabbled in the same forbidden practices that other court ladies did. But in the tense and treacherous political climate of the Lancastrian court, where rivalries were soon to explode into the War of the Roses, a mistake in judgment could cost one everything. As was learned by Eleanor Cobham.