Superlatives have always defined the story of the RMS Titanic. It was a ship described as the strongest and the most beautiful–and the most unsinkable. But in the end, it sunk in freezing cold waters on probably the most peaceful night on the ocean possible. The universal obsession with the ill-fated ocean liner does not stop here, however. It continues with the people who were traveling on board.

The lavish ship took only two hours and 40 minutes to sink. That was just enough time for more than 2,000 epic and tragic life stories to unfold on the Titanic, many of which are still being retold more than 105 years later.

Among the passengers, there were those who did almost anything to save their own life, including a man who dressed as a woman. There were also people who sent distress signals until the very last moments from the Marconi room. Then there was the captain, who remained on the bridge until the end. Hundreds more had realized they were probably going to die that night, as they waved goodbyes to their relatives being deployed in the lifeboats. Amid the confusion and the ongoing rescue procedures, there were also the band members of Titanic’s orchestra, without whom the entire picture of the ship’s sinking cannot be complete.

Titanic‘s musicians were a multi-national group of eight, who comprised one three-piece and one five-piece ensemble on the lavish ship. All of them had boarded at Southampton, registering as second-class passengers.

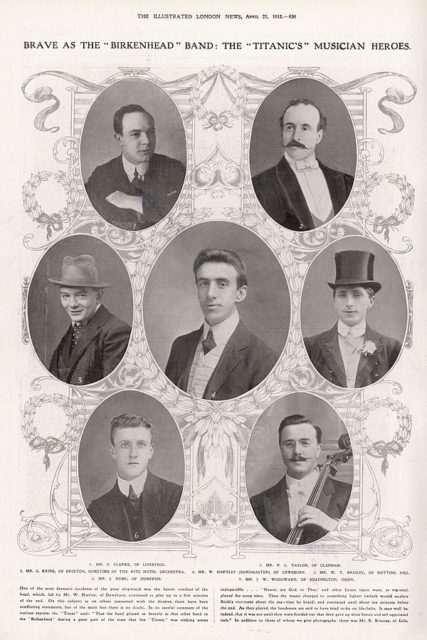

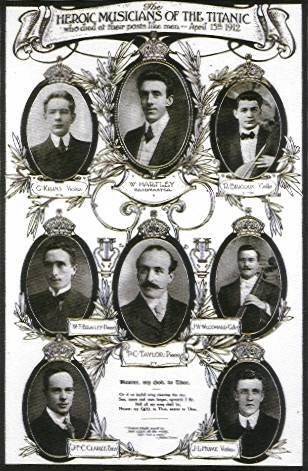

Georges Krins, Roger Bricoux, and Theodore Brailey were a violin, cello, and piano trio. Then there was the quintet led by Wallace Hartley, who was a violinist and the official bandleader. The quintet also featured a bassist, John Frederick Preston Clarke; two cellists, Percy Cornelius Taylor and John Wesley Woodward; and John Law Hume, who was also a violinist.

Titanic’s orchestra; at the top: Clarke; Taylor; in the middle: Krins, Hartley, Brailey; and at the bottom: Hume; Woodward. Not pictured: Bricoux.

When the ship hit the iceberg and began to sink, the band members, led by Hartley, kept playing music. Sadly, they all lost their lives as the ship perished in the depths of the ocean. Hartley’s body was one of the few recovered from the freezing waters afterward, and huge crowds would attend his funeral.

One second-class passenger remarkably described the last moments of their lives, saying, “Many brave things were done that night, but none was more brave than those done by men playing minute after minute as the ship settled quietly lower and lower in the sea. The music they played served alike as their own immortal requiem and their right to be recalled on the scrolls of undying fame.”

John Hume, like the rest of Hartley’s orchestra members, belonged to the British Amalgamated Musicians’ Union. They were all booked by White Star Line through a Liverpool-based firm known as C.W. & F.N. Black, a firm noted for providing musicians on many of the British liners.

However, what’s shocking is that after the sinking of the ship, on April 30, 1912, Hume’s father Andrew received the following note from the agency:

Dear Sir:

We shall be obliged if you will remit us the sum of 5s. 4d., which is owing to us as per enclosed statement.

We shall also be obliged if you will settle the enclosed uniform account.

Yours faithfully,

C.W. & F.N. Black

RMS Titanic Musicians’ Memorial, Southampton. Author: Marek. 69talk, CC BY-SA 3.0

The uniform account included items such as a lyre lapel insignia that cost 2 shillings, or White Star buttons on the tunic worth 1 shilling, and so forth. In total, the bill was 14 shillings and 7 pence, which Andrew Hume refused to settle. Instead, he had the note sent to the Amalgamated Musicians’ Union, which then published it in its monthly newsletter without any comment.

Reportedly, the entire story caused a huge controversy at the time. It certainly diminishes the superlatives surrounding the Titanic. It also tells of the changing social attitudes following the sinking of the Titanic.

Until 1912, the musicians had been paid 6 pounds and 10 shillings a month, plus they had a monthly allowance of 10 shillings specifically for the uniforms. The rates were then cut to 4 pounds a month and there was no uniform allowance, which could possibly explain the note.

It must have been shocking for the musicians’ families, who had lost their loved ones on the Titanic, to be billed for the uniforms they had worn.

At another end of the Titanic story, a week after the disastrous event, over 50 employees of White Star Line reportedly walked off from the RMS Olympic, Titanic’s sister ship, which was about to depart on a new voyage. They protested that more people could have been saved, including their own family members who had died in the sinking, if there were a sufficient number of lifeboats on the Titanic.

Furthermore, despite the famous order of “women and children first,” at least a third of the children on board perished in the waters. However, each child traveling in either first- or second-class was supposedly saved. The lower class children were the ones who died.

Engraving by Willy Stöwer from 1912, “Sinking of the Titanic.”

Amid all the developments after the hazard, and all the “what if” questions, something other than human lives went down with the Titanic. Maybe it was the illusion of order and organization in the world, or the strong belief in technological advancements, that must have dazzled many in the first decade of the 20th century.

As director James Cameron would accurately remark one day, “The Titanic disaster was the bursting of a bubble.” Things in society had started to fall apart, as Europe at that point was becoming deeply divided; a big war was coming. Perhaps that’s the reason why Titanic is so embedded in the collective memory of people, as a sort of lost world before the wars. In a smaller, yet potent, way, the story of the agency billing family members for the dead musicians’ uniforms strikes a note too.