The State Hermitage Museum in Russia’s Saint Petersburg, one of the most famous art museums in the world, has a staff including numerous specialists in sculpture, history, painting, but also, believe it or not, a special kind of four-legged specialists that work under the Jordan Staircase in the Hermitage’s Winter Palace. Yes, cats.

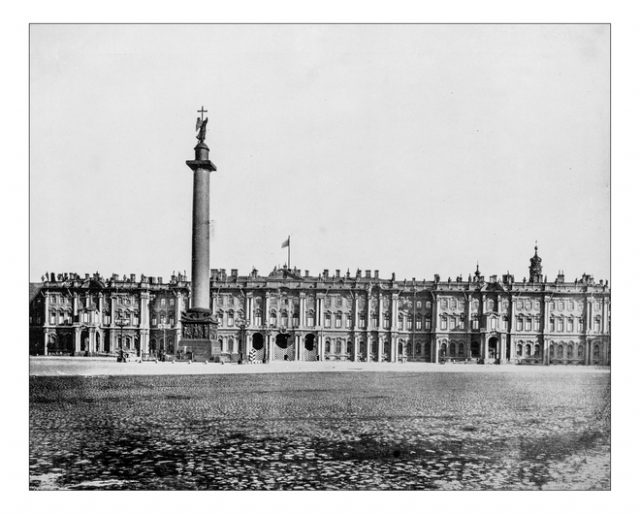

Understandably, one may wonder why domestic cats would roam the halls of the Hermitage. Historical records have shown that the museum has been the home of hundreds of cats since the 18th century. The largest building that integrates the entire Hermitage, the Winter Palace, was ordered as an official residence by Empress Elizabeth of Russia, the daughter of Peter the Great. It was designed by the architect Bartolomeo Rastrelli from 1754 to 1762.

The Jordan Staircase of the Winter Palace, by Konstantin Ukhtomsky

In 1795, the drafty hallways of the palace were infested with rats and mice, so the empress signed a decree on sending the cats to the high court, demanding that 13 cats from Chazan be dispatched to Saint Petersburg. Elizabeth’s preference for Chazan cats wasn’t a coincidence–this breed is considered the best ratter. The Chazan ratters that were brought to Saint Petersburg on the Empress Elizabeth’s orders left no offspring, though, because they had been neutered. The cats that followed, and which bred inside the palace, were descendants of the cats from the court of Catherine the Great. According to historians, she kept around 300 pets in the Hermitage.

One of the Hermitage cats. Author: ewwl CC BY-SA 3.0

Currently, there are over 70 cats and all of them live in the basement of the Winter Palace, which resembles a feline headquarters. They are fed and taken care of by volunteers. In Museum Secrets, one such volunteer explains that while some of the cats are friendly and ask to be cuddled, others, like the Siberian type, don’t really like humans and avoid being held.

Most of the daily visitors are immediately surprised and their hearts melt when they spot the cats of the Winter Palace, and some people even want to take these animals homes not only to keep them as pets but also because of their supposed healing powers. It is said that some of the cats in the Hermitage, like the red-and-white kind, have a strong aura against negative energy, so people consider it desirable to get a cat from the museum.

A room in the Winter Palace. Author: Ivanchay CC BY-SA 3.0

After the rule of Catherine the Great, the cats were granted the status of official rat catchers and became a beloved Russian pet. Ever since, they’ve been regarded as guards of the Hermitage Museum and the staff has even included special workers to look after the animals.

However, the Hermitage history also contains a somber scenario of cats’ lives in the museum during WWII. At the time, Saint Petersburg, then known as Leningrad, was besieged by the Germans, who marked the Hermitage for destruction. Thus the museum was under siege too. The staff schemed to save the museum’s masterpieces but the cats, one by one, began to disappear. Thousands of people looked for shelter in the museum, escaping the bombs and the soldiers, and the hungry had little choice but to turn the cats into victims of human hunger.

Today, hundreds of tourists from all over the word stroll around the magnificent halls of the Hermitage, admiring its diamonds, Egyptian remains, Greek Statuary, and other treasures, but the notion of the underground residents who have been occupying the museum’s basement for the last 250 years is a really special attraction that distinguishes and contributes to the Hermitage’s authenticity.

Antique photograph of Winter Palace seen from Palace Square in 19th century. The monumental building was the official residence of the Russian monarchs

The assistant director of the State Hermitage Museum, Maria Khaltunen, stated: “We do not have rare or exclusive breeds, our cats are ordinary, mostly crossbreeds. While some are good at mice hunting, the rest just scare off the rodents with their looks.”

Though the cute whiskered creatures ought to patrol the basement, sometimes they disobey the rules and sneak into the galleries. Obviously they have good taste in art, too.