Almost before the ink was dry on the Treaty of Versailles which ended WWI, officers in the armed forces of Germany had begun to plan ways around it. Their ultimate aim was that one day they could announce to the world that they were no longer going to follow its dictates.

Obviously, some of the terms of the treaty could not be avoided. For example, Germany’s territory was divided: East Prussia was separated from the rest of the nation by the so-called “Polish Corridor”, and the Rhineland and Saar-land were occupied by foreign forces. Alsace-Lorraine was French territory (again) and reparations needed to be made.

All of this was a very bitter pill for most Germans to swallow. However, although these terms were widely resented, they were nothing compared to the restrictions that were put on Germany’s armed forces. In the eyes of the Allies, the popular opinion was that Germany had begun the wars in 1870 and 1914. As a result, the ability of the Germans to wage war needed to be severely limited.

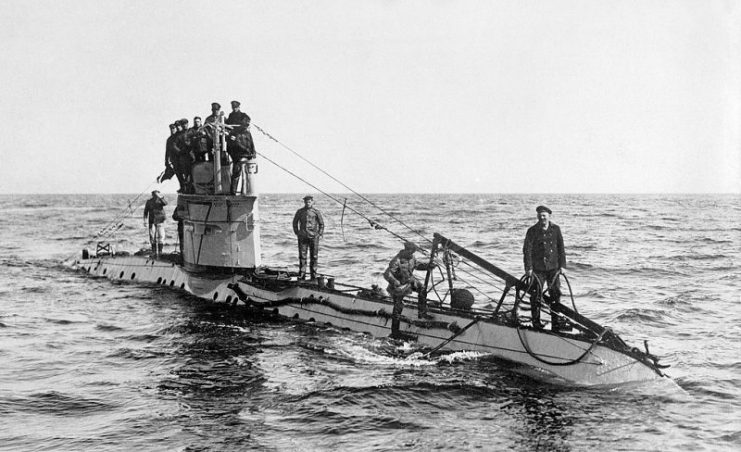

German armed forces would be allowed 100,000 men for self-defense and internal control. Germany was to have no air forces, and the Kriegsmarine (navy) was to be severely limited. In particular, they were to have no submarines at all. The German U-Boats had taken a severe toll on Allied shipping, including the infamous sinking of ocean liners carrying civilians.

History classes covering WWI and the rise of Hitler thankfully still cover all of this, but what many teachers leave out is the importance of the armed forces to the German psyche. One could make the argument that the German national myth included the fact that Germany was never conquered by Rome.

In contrast, the Germans had inflicted such a defeat on the Romans at Teutoberg Forest in 9 AD that the Empire never seriously attempted to take them on again. Since that time, war and warrior culture had been a part of German life.

In Prussian and other German states before unification, the army and military culture played a central role in the lives of many. Aristocratic families with sons would send at least one of them into the military.

In addition to the aspects of conquest, self-defense, and patriotism, a military career was one of the most popular career paths in pre-WWI Germany. A man who had made a career in the army, no matter what his rank, was a highly respected person in German society.

Officers, especially those with a record of success on the battlefield, could in many ways be compared to today’s movie stars: men wanted to be like them, and women wanted to be with them. By limiting the German armed forces to 100,000 men, the Allies were taking away the planned future of literally millions of men.

All of this fed into the resentment that eventually led to Hitler, but even before the rise of the Nazis, other Germans were already working on rebuilding Germany’s power in secret. General Hans von Seeckt is given much of the credit for this, but his focus was on the army and the air forces.

Interestingly enough, much of the secret rebuilding, research, and planning of the German army took place in the Soviet Union in the 1920s. By helping the Germans rebuild, the Soviets were in many ways sowing the seeds of the destruction they suffered in 1941 when Germany invaded the USSR.

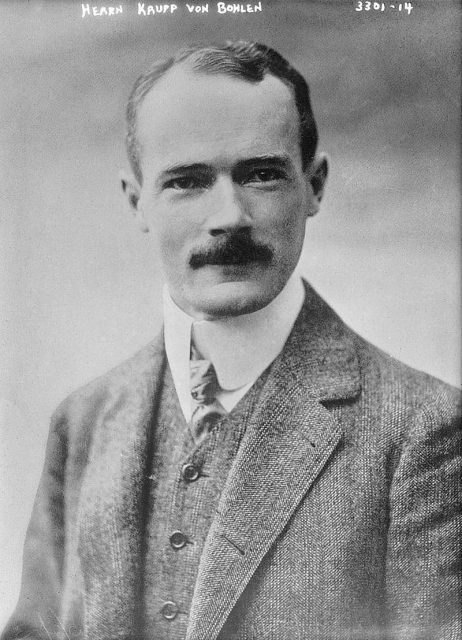

Similarly, the German Navy, which was limited to patrol craft and old destroyers, conspired with foreign nations and companies for the construction and designing of submarines in the years before and just after Hitler came to power. Steel producer Krupp, which was perhaps the largest company in Germany and one of the largest in the world, was central to the development of German submarines in the inter-war years.

The head of the Krupp family and its industries was Gustav von Krupp. In 1922, Krupp sent the first group of what would eventually total forty German engineers to Holland. There they would work at NV Ingenieurskantoor voor Scheepsbouw (NV being a Dutch business law term and the rest meaning “Engineer Office for Shipbuilding”). This company, while employing Dutch people, was a shell company set up and financed by the German Navy, a Krupp subsidiary, and two other German shipping companies, AG Vulcan and AG Weser.

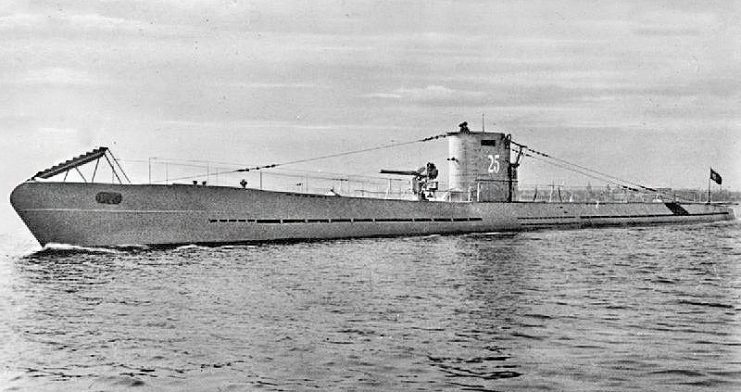

Here, German naval engineers and designers would plan and build submarines for other nations, but the true purpose was to have ready-made plans and experienced engineers for any future German U-boat force. Another German shell company, Crichton-Vulcan, was set up in Finland.

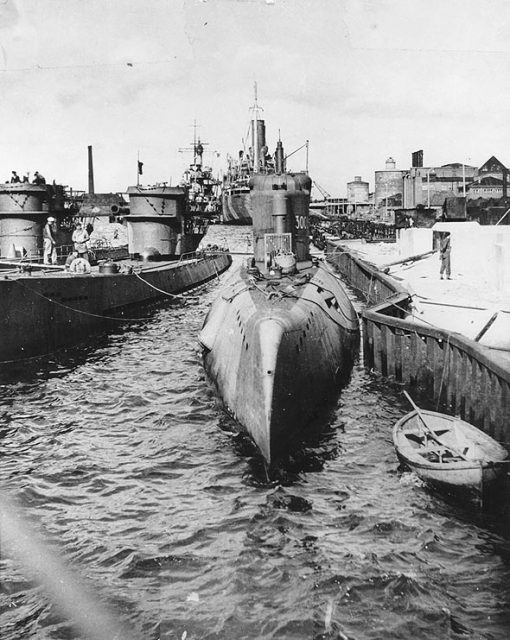

Finland, a friendly nation that would be Germany’s ally for much of WWII, would benefit from allowing the Germans to work on sub designs. The submarines which resulted from this work, the Vesikko (Finnish for “mink”), would provide the Germans with the prototype for their Type II U-Boat which served Germany well in the first part of WWII. Today, the Vesikkoserves as a museum in coastal Finland.

However, Germany did not keep the U-boats built by these shell companies – that would have drawn the attention and ire of Britain and France. But they did sell subs to Spain, Turkey, and Holland and the cash from these sales helped to fund the program.

While German engineers trained in Holland and Finland, German naval officers and men were training in civilian clothes at the cleverly named “Anti-Submarine Warfare School” in the German port of Kiel.

Like their compatriots in the army training in the Soviet Union, class after class of German officers and men trained in “anti-submarine warfare”, then went to Finland or Holland to gain actual experience aboard German built and designed U-boats. These cadres would form the backbone of the German submarine force at the outbreak of WWII and strike terror into the hearts of Englishmen such as Winston Churchill.

When Hitler repudiated the Versailles Treaty in the mid-30s, Germany already had a large number of trained men, years of perfecting sub designs, and some of the leading steel companies of the world who had secretly been building submarines for years. Though German sub fleet commander Admiral Dönitz wanted more subs than he had when the war began, if it wasn’t for this secret program, he might have had none at all.