Public execution and torture as criminal punishment goes back a long way in European history. Often the sentence was engineered to fit the crime, in some unthinkably gruesome ways.

In France, during the period from 1789 to 1799, hundreds of thousands of men and women were arrested and tens of thousands executed in the name of the French Revolution. One prominent episode concerns Thomas de Mahy, Marquis de Favras, a high-profile nobleman who was hanged in 1790 for plotting to rescue King Louis XVI and his wife, Marie Antoinette.

The Marquis de Favras was born in 1745 and was distinguished for his service in the army. His hanging marked an important turning point as he was the first nobleman for whom there was no class distinction in his mode of execution. By tradition, nobles were spared from a drawn-out public humiliation — those sentenced to death would receive a swift beheading by axe or sword.

Commoners, in contrast, were made a spectacle of. One of the least brutal, although far from dignified, methods of execution was strangulation by hanging.

The execution of the Marquis de Favras on February 19, 1790, in Paris.

The Marquis did not have the fortunes to fit tradition. The times, they were changing. Crowds of people gathered for his public hanging on Place de Greve on February 19, 1790, with many cheering “Encore!”

After he was executed, the French guards struggled to protect the body of the Marquis from being further mutilated by the crowd, who wanted to see his head mounted on a pike.

But how exactly did Thomas de Mahy anger Parisians so much?

Favras Family

The country was on the edge of a financial crisis after funding years of warfare but the royal couple continued to spend money as extravagantly as their predecessors. Drought and successive failed harvests did not stop Louis XVI demanding higher taxes — the angered populace finally cracked. When revolutionists stormed the Bastille fortress on July 14, 1789, the royal couple were captured and held at Tuileries Palace in Paris.

The Marquis de Favras initially supported the societal changes that were looming upon France, at least until he realized the extent to which the Revolution degraded the royals so near and dear to him. Disillusioned with the violence, the Marquis got involved in a counter-movement, along with Louis Stanislas Xavier, Comte de Provence, the brother of Louis XVI.

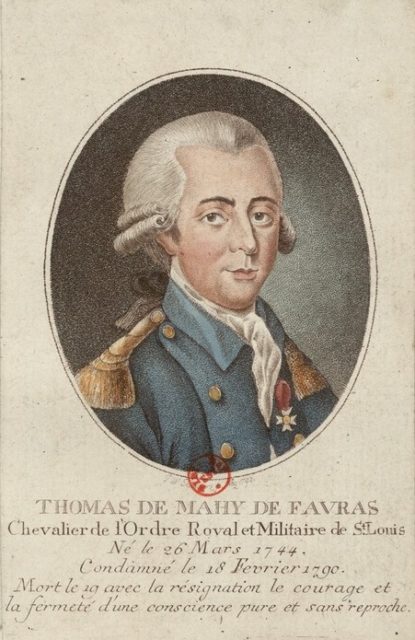

“Thomas de Mahy de Favras, Knight of the Royal and Military Order of St. Louis, born on March 26, 1744, condemned on February 18, 1790, died on the 19th with resignation the courage and firmness of a pure conscience and without reproach.”

It’s safe to say that the Marquis de Favras was in a way used as a scapegoat by the Comte. If there was one mastermind to the entire plot, that was probably the Comte de Provence, and he needed the help of someone as loyal as de Favras.

Favras acted recklessly as he went on with preparations. He disclosed information about the plot to the wrong people and someone betrayed him.

A leaflet was circulated around Paris and it damaged the reputation of the noble. It claimed that he aimed to rescue the royal couple, but also revealed a range of other plans. Some of these plans included killing public figures like the Mayor of Paris, Sylvain Bailly, and the commander of the National Guard, the Marquis de Lafayette.

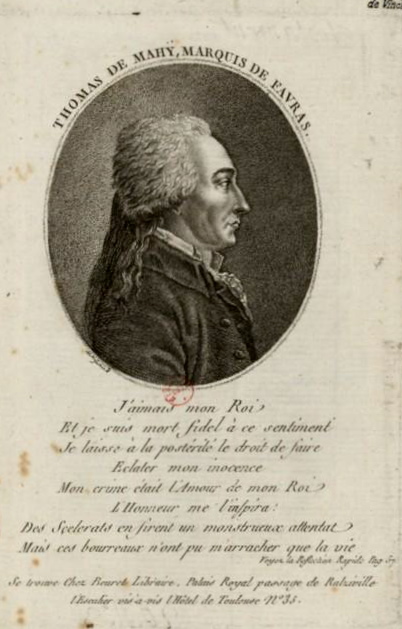

Portrait of Monsieur le marquis de Favras in the Journal de Paris, February 20, 1790.

It also outlined a scheme to make the Comte de Provence the next reigning monarch (he did eventually became Louis XVIII of France, but not until 1814).

More of the plot? Gather 30,000 troops and lay siege the capital. Starve people so they forget about their revolutionary ideas. Magnifique! Except it wasn’t Magnifique — Thomas de Mahy, Marquis de Favras, was suddenly detested by everyone.

The leaflet had angered Parisians enough that the Marquis de Favras was arrested. He was initially held in Abbaye Prison.

To make things worse for the Marquis, the Comte de Provence, whose name appeared in the leaflet, didn’t waste time in disassociating himself from his loyal servant and friend. He was seemingly diplomatic, praising the revolution and the people. While the Comte was applauded, the Marquis was condemned.

Thomas de Mahy, Marquis de Favras, was sentenced to death in 1790 after being accused of plotting to save the royal family.

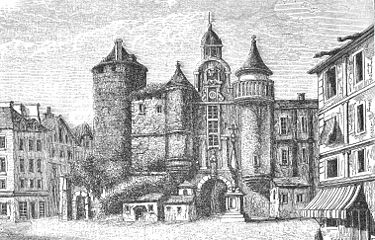

He was relocated to Grand Châtelet (today the site is occupied by the Place du Châtelet) which accommodated a courthouse, as well as facilities of both the police and the prison. The Grand Châtelet was heavily secured by guards during the trial to ensure the mob outside didn’t take justice into their own hands.

The trial progressed slowly. What served as the most compelling piece of evidence was a letter sent to Marquis de Favras by a supporter of the conspiracy. The contents of the letter revolved around the alleged troops that were to besiege Paris.

The Grand Châtelet c. 1800, looking south from Rue Saint-Denis.

It was an insubstantial piece of proof. The supporter of the plot had asked de Mahy in the letter “Where are your troops? … From what direction will they enter Paris?” and stated “I would like to serve among them.”

And that was it. The plan was probably still not ripe enough to happen.

At one point during the two-month-long trial, the Marquis reportedly gave out names of people who were in some way involved with the plot, however, he would not exchange more details than that. He was ready to reveal greater details only if relieved of blame. But that did not happen.

Thomas de Mahy, Marquis de Favras (1744-1790).

Thomas de Mahy, Marquis de Favras, was sentenced to death by hanging on February 18, 1790, for the charge of treason.

The most intriguing part? When he read through the order for his execution, the Marquis de Favras muttered: “I see that you have made three spelling mistakes.”

With or without mistakes, the warrant was placed in order. His death took place the following day. The quote has become famous because the Marquis kept his sangfroid in the face of a painful and humiliating death, and he is revered by those who uphold the importance of correct grammar and spelling.

De Mahy was reportedly deeply mourned by the royals. His widow, Madame de Favras, was later provided a pension by the Crown.

As for Louis XVI and his wife Marie Antoinette, they were both guillotined in 1793.