The Vintage News

Dec 29, 2018 James Hoare

Like large parts of Europe, the remote sub-arctic island of Iceland became gripped by witch terror in the 17th century.

Sparsely populated, mountainous, and volcanic, Iceland had been settled in the 9th century by outcasts, outlaws and adventurers looking for freedom and opportunity away from the Viking kingdoms in England and Norway.

Life on this eerie island was harsh, but these strongly independent and hardy people – even by Viking standards – endured.

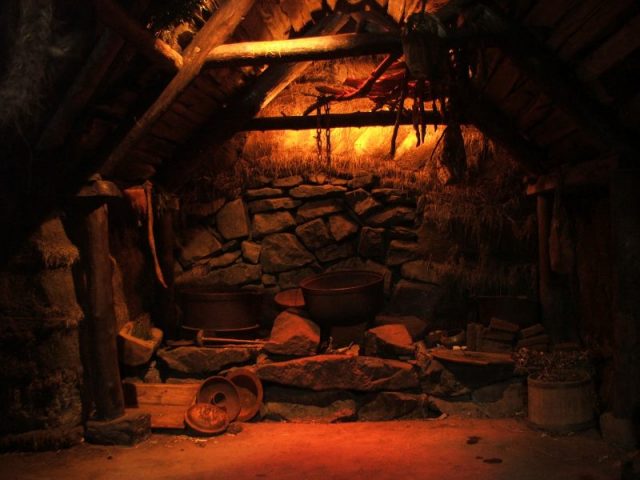

Replica Viking village, Höfn i Hornafirdi, Iceland.

Their rebel status ended in the 13th century when Iceland became part of the Kingdom of Norway, and then in the 16th century was inherited by the Kingdom of Denmark.

Denmark was the witch hunting capital of Scandinavia. It was from Denmark and his Danish wife Anne that Scotland’s King James VI (later to become England’s King James I as well) got many of his ideas about the grave threat posed by the Devil and his minions, and how to battle them — with sword and flame.

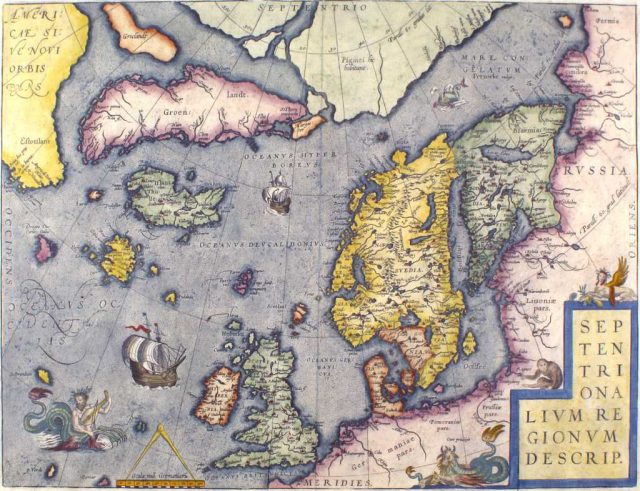

A map of Scandinavia and Britain from the 16th century, showing Iceland in green in the top left.

James VI wrote up his murderous supernatural fantasies in his notorious witch hunting manual Daemonologie, which was a major part of the Salem witch trials in 1692 and 1693.

With Danish influence over this wild island in the bitterly cold north bringing with it a deep-seated fear of black magic, Iceland executed its first witch in 1625. Unlike the vast majority of European witch trials, this so-called “witch”, Jon Rognvaldsson, was a man.

Sorcerer of Strandir. Photo by Ágúst Atlason

Over the next 50 years roughly 120 witch trials were held in Iceland. The vast majority of the accused were men. Of the 22 Icelanders burnt on the pile of their own goods (trees were too scarce and valuable to waste on funeral pyres) for witchcraft, all but one were men.

A relatively late convert to Christianity due to its remote location on the furthest edge of Northern Europe, pagan Norse magic and rituals survived in Iceland right up to the 17th century.

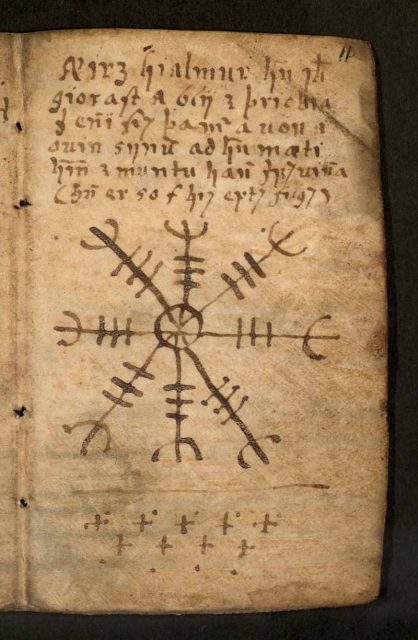

Icelandic grimoire – the magical sign Ægishjálmur.

In pre-Christian Norse society, magic was loosely divided into male and female spheres, with men most frequently involved in the casting of special runes – carved into bone, wood or stone – for advice or prophecy, or inscribing runes as a protection or curse.

As a result most Icelandic witch trials involved men being found with runes, and accused of all manner of ills. Jon Rognvaldsson, for example, was accused of summoning a ghost to kill several horses and injure a child – the “proof” was a sheet of paper that he admitted to writing runes on.

Witch Burned at the Stake

By no means universal, the most common formula in a European witch hunt was that some poor old woman on the edge of a village was heard muttering something under her breath.

She was then blamed for some misfortune – a sickness, a stroke, the death of livestock – that followed.

Iceland in the 16th century had no villages and it had no mysterious old women living alone.

Inside The Sorcerer’s Cottage. Photo by Sigurður Atlason

People lived and worked together in turf-covered farmsteads. In this harsh environment anyone who lived by themselves would have died of cold or starvation, so widows had to be part of a larger household to survive.

This was a poor country and these were small farms, so there was no privacy. What this meant is no “crones” were going door to door begging and being refused, and nobody was living alone where rumours could start to spread about what they got up to behind closed doors.

Museum of Icelandic Sorcery & Witchcraft. Photo by Jennifer Boyer CC BY 2.0

Although the Danish law against witchcraft was officially proclaimed in Iceland in 1630, the Icelandic elite had good reason for ignoring it as much as they could. They also knew “their magic” was different from what was described by the Danes.

The reason was that the writing and reading of runes wasn’t just a man’s business, it was an educated man’s business.

Museum of Icelandic Sorcery & Witchcraft. Photo by Jennifer Boyer CC BY 2.0

With educated men being the wealthy and influential, many of the same people expected to enforce laws against witchcraft were most likely to using rune magic themselves.

These men were less likely to turn on a suspected witch if they thought the magic was benign – done for self-protection, healing, or to protect their livestock.

On the other hand, this also meant that they were quick to identify their own magic being used for evil ends (called maleficum in Latin). So while witch hunters in the rest of Europe relied on the bizarre methods outlined in manuals like Daemonologie or the Malleus Maleficarum – looking for a “devil’s mark” where a familiar was said to suckle on the witch’s body, or testing to see if the suspect sunk or floated – these weren’t used or even widely known of in Iceland.

Instead, if an Icelandic witch hunter believed magic had been used to cause harm, he’d go looking for runes and the man who had used them.