Isaac Newton was a 17thcentury colossus, whose writings were a driving force behind the way we think about the world today. His work was influential on the Enlightenment, or “Age of Reason,” which took humankind away from magic and towards rationality and scientific principle.

Based on this, it’s easy to categorize Newton as a purely rational being and uninterested in the more fantastical side of life. However, that isn’t strictly true. The relationship between science and the occult in those days was more complex and certainly more interactive than some might think.

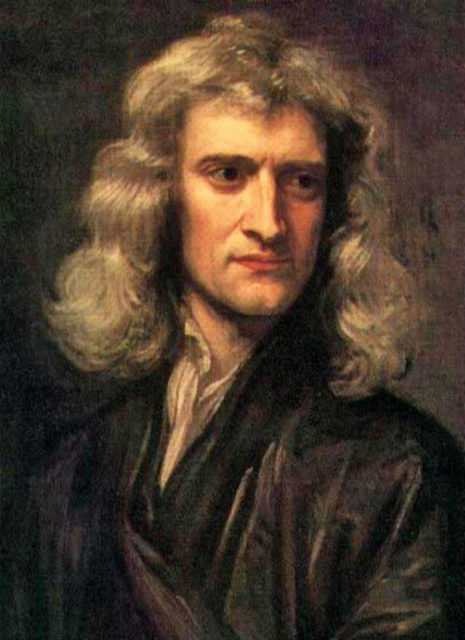

Portrait of Newton in 1689 by Godfrey Kneller.

The most famous story about him relates to his theories on gravity, and how he was inspired after an apple fell out of a tree and hit him on the head. This is actually a good starting point for a look at Newton’s occult interests. Whether the fruit incident occurred in such a dramatic way is a matter for debate. If it did happen, there is an intriguing element to this act of Mother Nature that could arguably be called religious.

The tree from which the famous apple is said to have fallen. Photo By Fritzbruno CC BY-SA 3.0

Just because he was a man of science did not make Newton a non-believer. Milka Levy-Rubin is an academic at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. In 2012 she was quoted by the Daily Mail in reference to Newton’s occult writings, which were published online by Israel’s National Library:

“Today, we tend to make a distinction between science and faith, but to Newton, it was all part of the same world… He believed that careful study of holy texts was a type of science, that if analyzed correctly could predict what was to come.” A Christian, Newton was interested in Kabbala, an interpretation of the Bible rooted in Jewish mysticism, in addition to other disciplines.

Newton in a 1702 portrait by Godfrey Kneller.

One of the focuses of his studies was the Book of Daniel, with its portents of apocalyptic destruction. Newton himself believed the world would end in 2060. He saw the ancient descriptions of Solomon’s Temple as significant to Mankind’s place in the order of things, and pored over its geometry, leading his own reconstruction of the building.

Philosopher’s stone as pictured in Atalanta Fugiens Emblem 21

He also had a keen interest in alchemy, or the art of refining substances to recreate them in their purest form. This predated modern chemistry, which had yet to take shape in Newton’s time.

Way before Harry Potter heard about the Philosopher’s Stone, Newton looked to make it a reality. Far from being a stone, it was a powder with the supposed ability to transform base metals into gold, the benchmark of alchemical practice.

The Alchymist, in Search of the Philosopher’s Stone by Joseph Wright of Derby, 1771.

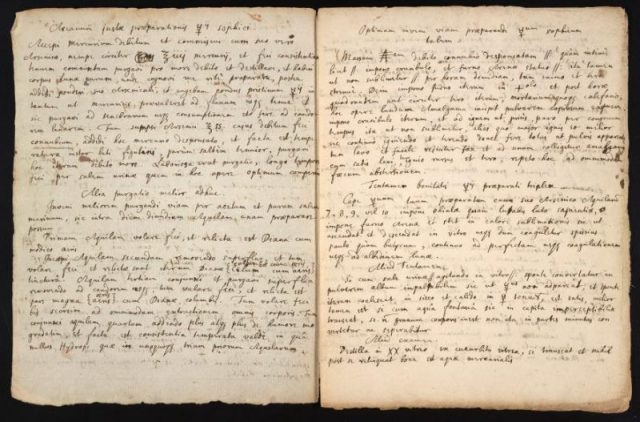

A National Geographic article from 2016 covers the unveiling of a manuscript written by Newton containing a recipe for “sophick mercury.” Together with other ingredients, this forms part of the Philosopher’s Stone. The piece talks about the extent to which the physicist was invested in alchemy and its methods:

“Newton wrote more than one million words about alchemy throughout his life, in the hope of using ancient knowledge to better explain the nature of matter—and possibly strike it rich. But academics have long tiptoed around this connection since alchemy is usually dismissed as mystical pseudoscience full of fanciful, discredited processes.”

Newton copied the recipe from American alchemist’s writings. Photo by Chemical Heritage Foundation

Indeed, even his admirers were surprised he was toiling away in his laboratory on something associated more with magic than science.

Alchemists gained respect from historians over the years, who came to appreciate their hard work and meticulous efforts. This makes it easier to accept one of the cornerstones of the rational age as a mystical practitioner. It stands to reason however that one day people will look back on the science of this age and wonder how such primitive concepts were ever taken seriously.