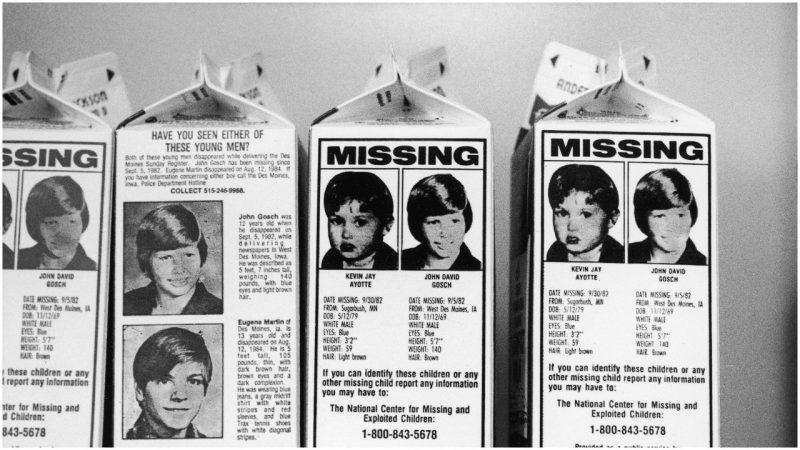

Have you seen this child? Long before Amber Alerts and push notifications, reports of missing boys and girls appeared in a place guaranteed to catch the eyes of the widest range of Americans, young and old, rich and poor, rural and urban: on the sides of milk cartons in the 1980s. With grainy black-and-white photos, their name, age, and date of disappearance, this generation of lost children became known as the Milk-carton Kids.

“Their faces will be there at the breakfast table,” Joe Mayo, a police commander in Chicago told the Associated Press in 1985, shortly after the program launched. “People will have to think about it.”

Media in the early 1980s was a vastly different landscape than it is today. There were few national newspapers. Real-time broadcasting on CNN was a strange new experiment. There was no worldwide web on which to distribute information. Reporting emergencies meant picking up a telephone and dialing a number. It seems strange today, but then parents of missing children might use a Xerox machine to make copies of photos, list details, and plaster posters on telephones around the neighborhood.

So how did missing kids wind up on milk cartons? The story is traced back to the Midwest. A newspaper delivery boy named Eugene Martin went missing near Des Moines, Iowa, in 1984. He was the second paperboy in as many years to disappear. A relative who worked at the nearby Anderson & Erickson Dairy asked his employer to help, according to the podcast 99 Percent Invisible. Within weeks, milk cartons featuring the photos and names of both newspaper boys were distributed in the area. (The missing kids’ photos replaced the usual advertisements on the milk cartons.)

This is a photograph of Etan Patz taken by his father, Stanley K. Patz, on September 16th, 1978. Author: Stanleykpatz CC-BY 3.0

In December of 1984, the National Child Safety Council (NCSC) adopted and expanded the Missing Children Milk Carton Program to help locate the estimated 1.8 million children who disappeared every year. “Photographs and biographies of missing children were placed on millions of milk carton side panels, bringing the faces of abducted children and the reality of this national disaster directly to countless Americans and individuals worldwide,” the NCSC noted. “All the layouts and camera-ready artwork are supplied by the Council without charge of any kind to carton manufacturers.”

Etan Patz was the first child to be featured on a national milk carton campaign. He had disappeared in 1979, a six-year-old walking a block to a bus stop in New York City’s SoHo neighborhood. Though Manhattan was grittier then than it is today, the neighborhood was considered relatively safe; people knew one another. Patz’s disappearance caused parents across the country to wonder if their own children were safe walking to school. The Patz family worked tirelessly with other parents to raise awareness about child abductions.

The milk-carton program proved so popular that it migrated to other products: Photos of missing kids showed up on paper grocery bags, in telephone directories, and even on pizza boxes. It entered the pop-culture lexicon. “The Face on the Milk Carton,” by Caroline B. Cooney, became a young reader bestseller in 1990. The Milk Carton Kids became the name of a folk duo in 2011.

An estimated 5 billion milk cartons were distributed during the program’s heyday, though its successes were few. Most kids were never found, including the two paperboys whose disappearance sparked the program and young Patz. Many years later a former store clerk confessed to murdering Patz and was sentenced to jail this past February, though the boy’s body was never recovered.

One astonishing exception is a little girl who discovered a photo of herself on the side of a milk carton, as reported by 99 Percent Invisible. Bonnie Lohman had been taken from her father when she was 3 by her mother and her stepfather. At age 7, she came across a photo of herself, though she couldn’t read the words MISSING CHILD. Her stepfather bought the milk and allowed Bonnie to keep the photo, though he warned her not to show it to anyone. Eventually, her neighbors saw the photo and called the police; Bonnie was reunited with her father.

(Indeed, despite widespread and deep-rooted fear of “stranger danger,” most children who are abducted are taken by people who know them. Around 800,000 children go missing every year, according to the National Center for Missing and Abducted Children; between 100 to 200 of those are abducted by strangers.)

The Milk Carton Campaign did launch a coordinated and concerted effort to locate missing children. The AMBER Alert system was established in 1996. Today alerts are texted to cellphones, broadcast on roadside digital billboards, and transmitted on NOAA Weather Radio. In 2015, 182 AMBER alerts were issued; 153 cases resulted in recovery.