May 18, 2018 Barbara Stepko

The enemy—numbering in the thousands—was relentless, surrounding Napoleon and his men, eventually bringing them to their knees. In desperation, they would retreat.

Waterloo, you’re thinking? Not exactly. Napoleon’s most memorable—and humiliating—defeat came at the hands, well, the paws of a fearsome band of bunny rabbits.

The bizarre moment in European history happened in July of 1807, after Napoleon signed the Treaties of Tilsit, officially marking the end of the war between the French Empire and Imperial Russia. To celebrate the occasion, he proposed a rabbit hunt with his men and some military big-wigs. Being a busy man, Napoleon put his chief of staff, Alexandre Berthier, in charge of organizing the event.

Big mistake.

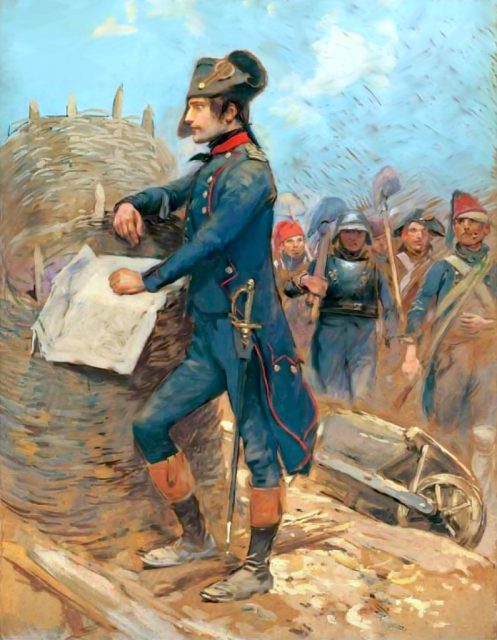

Bonaparte at the Pont d’Arcole, by Baron Antoine-Jean Gros, (ca. 1801), Musée du Louvre, Paris

Berthier set out collecting rabbits for the big hunt, but never one to do things in a modest way, Berthier went a tad overboard with the bunny corralling. Accounts of the event estimate that he collected somewhere between several hundred and 3,000 rabbits. In any case, it was a bevy of bunnies.

/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/bonaparte-at-the-siege-of-toulon.jpg

The day of the hunt, Berthier’s men rounded up the rabbits and placed the cages all along the edges of a massive field. When Napoleon and his guests arrived, the long-ears were released and the hunt was on, as the hunters galloped into the field to catch their quarry.

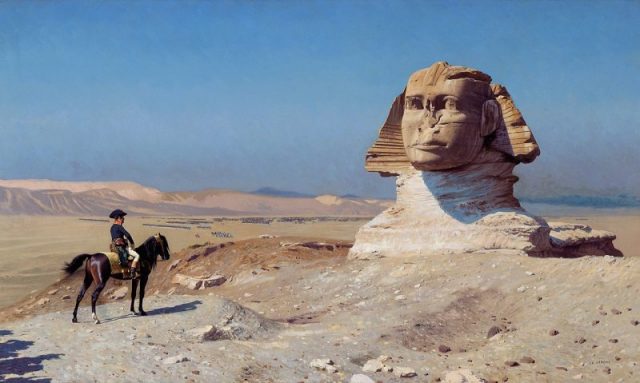

Bonaparte Before the Sphinx, (ca. 1868) by Jean-Léon Gérôme

But then something bizarre happened: The rabbits didn’t scamper away in fear. Quite the opposite: They bounded toward Napoleon and his hunting party, not unlike revolutionary rowdies storming the Bastille. Napoleon and his buddies soon found themselves bombarded with a barrage of fluffy bunnies. (Imagine Hitchcock’s The Birds recast with rabbits instead of crows. )

Initially, the men had a good laugh at the utter absurdity of it all—who wouldn’t? But as the onslaught continued, their feelings of mirth and astonishment turned into genuine concern and fear. The emperor and his men tried in vain to repel the onslaught, beating them off with whatever was handy—riding crops, sticks, muskets. Napoleon even tried shooting them, but the critters kept coming … and coming … and he and his men were absurdly outnumbered.

Bonaparte during the Italian campaign in 1797

Knowing it was a battle he could not win, Napoleon bid a hasty adieu, withdrawing to what he assumed would be the safety of his carriage. Not so fast, Monsieur! The flood of nonplussed cottontails continued to pounce. Historian David Chandler described the semi-comic carnage thusly: “With a finer understanding of Napoleonic strategy than most of his generals, the rabbit horde divided into two wings and poured around the flanks of the party and headed for the imperial coach.”

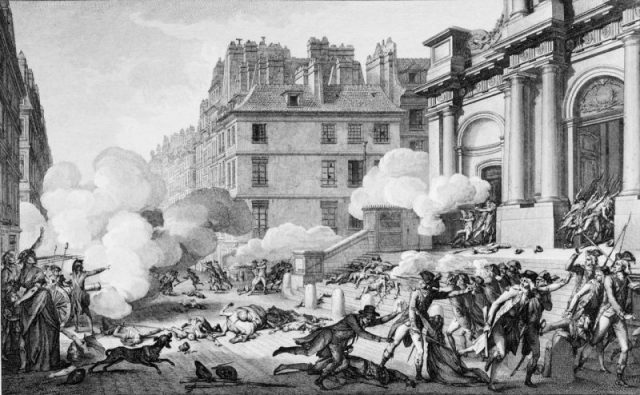

Journée du 13 Vendémiaire, artillery fire in front of the Church of Saint-Roch, Paris, Rue Saint-Honoré

The coachmen cracked their bullwhips in an effort to stop the assault, but to no avail. Before long, the horde swamped the little emperor’s little legs and started to climb up his jacket. A few of the rabbits actually leaped into his carriage. The attack ended only when the coach rolled away, with Napoleon, according to lore, flinging rabbits out of the windows of his cabin as they traveled.

Napoleon Bonaparte, aged 23, lieutenant-colonel of a battalion of Corsican Republican volunteers. Portrait by Henri Félix Emmanuel Philippoteaux.

So, you may be asking: Why did the rabbits attack? Blame it on Berthier. Though he may have been adept at military matters, he clearly wasn’t the brightest bulb when it came to animal husbandry. Rather than hunting down and trapping wild hares, he took the easy way out, ordering his men to procure tame rabbits raised by farmers in nearby towns.

Portrait of Napoleon in his forties, in high-ranking white and dark blue military dress uniform.

Problem was, unlike wild rabbits that would instinctively scurry away, the domesticated farm rabbits didn’t fear people. They took one look at Napoleon and his posse and assumed they were going to provide them with food, just like the farmers who raised them. When crispy carrots and heads of lettuce were not forthcoming, well, the critters got a little cranky.

All in all, you might say, it was a bad hare day.