For thousands of years, no one could figure out how the massive blocks of stone were brought from locations that were over 100 miles from the Giza Valley to build the tomb of King Khufu, pharaoh of Egypt from 2589 BC to 2566 B.C.

According to a new documentary, Egypt’s Great Pyramid: The New Evidence, Khufu’s engineers solved the problem of transporting materials by rerouting the Nile River to within feet of the building site. Khufu’s engineers came up with the ambitious idea of hand-digging canals deep and wide enough to carry transport boats and setting up a system of dykes to control the flow of the Nile.

Armed with this information, Mark Lehner, Egyptologist and expert on the Giza Valley, went to the pyramid and tested the soil surrounding the area. The samples that came up started with the expected desert sand, but then turned into the compacted clay from silt found only at the bottom of the Nile River. This led to the team discovering a basin area in the valley and canals dug deep into the soil creating a man-made port allowing the boats to deliver the rocks.

Giza pyramids Author: Ricardo Liberato CC BY-SA 2.0

Researchers have recently discovered papyri buried at the base of the pyramid. The papyri, being translated by Pierre Tali, were found in partial pieces as well as full sheets and gave detailed information about how ships were built and sailed down the Nile. There was even a disassembled boat ready to be put back together in case Pharaoh needed it in the afterlife. The papyri turned out to be the diary of Merer, a sailor in charge of a ship that transported some of the stones to Giza.

Aerial photography, taken from Eduard Spelterini’s balloon on 21 November 1904

Mohammed abd El-Maguid of the Central Department of Underwater Antiquities in Egypt took the instructions found in the papyri and built a boat in order to travel to the same quarry used by the ancient Egyptians building the pyramid. Mohammed also examined the burial vault of an ancient Egyptian boat builder and found hieroglyphs portraying the construction of boats. He learned what tools the Egyptians used in order to faithfully re-create the experience. He had his workers reconstruct the eight-yard-long boat that was tied together with rope rather than using nails or bolts. One thousand holes cut into the boat used three miles of rope to connect it together. It was waterproofed by lowering the completed boat into the water allowing the joints to swell and the ropes to shrink pulling the boards tightly together to form a water tight vessel.

Map of Giza pyramid complex – “Pyramid of Khufu” refers to the Great Pyramid.

In the meantime, workers at the same limestone quarry used by the builders of the pyramid were carving out a block of limestone by hand just as the ancient Egyptians did. It took 12 men two hours to carve out the 70-ton rock. The block of limestone was loaded onto the modern boat using a crane, but Mohammed believes the Egyptians’ rocks were cracked before loading to make the work easier. The rocks had to be in very specific positions to keep the boat upright. As the quarries were upstream of the valley, the workers could easily row with the current and then use their sails to move the empty boat back up the river for another load. When Muhammed’s boat was sailing, they tried to move across the river rather than along with the current and found this was nearly impossible. They realized in order to succeed, they must mimic the ancient Egyptians and arrived with the limestone and boat intact.

The entrance of the Pyramid Author: Olaf Tausch CC-BY 3.0

The Great Pyramid of Giza is one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, and the Nile River is the blood of Egypt. Without the river, there would have been no pyramids, no crops, and no population. To the ancient Egyptians, the Pharaoh was Egypt. He was their god-king, and everything happened due to his whim. When Pharaoh was happy, the river flowed and crops were good. If Pharaoh was unhappy, there may have been a draught or crop failure of some kind. The Egyptians did everything they could to keep Pharaoh happy, including building the enormous pyramid to house and protect his body after death.

Sarcophagus in the King’s chamber

While it was originally thought that the pyramids were built using slave labor, it has recently been determined that the average Egyptian male was required to do a certain amount of community service during his lifetime. Each man was allowed to work several months on a project and then returned to his home life. The workers were well fed with meat, bread, and beer and were accommodated in barracks built just across from the worksite. The workers were divided into teams of 40 with clear goals set to keep the project on task. Many of the workers on Khufu’s pyramid were among the better class of Egyptians with specific talents, rather than just rounding up workers.

The Grand Gallery of the Great Pyramid of Giza Author: Pprevos

CC BY-SA 3.0

The remains of the barracks have turned up thousands of shards of clay vessels used by the workers, and each vessel is branded with the name of the specific team that used them showing how Khufu used teamwork and camaraderie to get the work done.

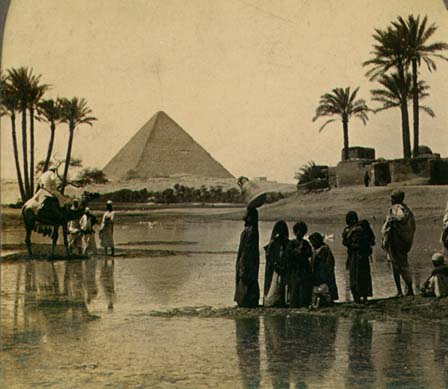

Great Pyramid of Giza from a 19th-century stereopticon card photo

It is still not clear how the heavy rocks were put into place, but according to the Egyptian Tourism Authority, French architect Jean Pierre Houdin, who worked on his theories for 10 years, has determined that the workers may have used ramps both inside and out. He theorizes that the limestone casing was built first and the rest of the rocks were placed later in a spiral fashion. Houdin and his team have been given permission to scale the Pyramid for up close inspection.

With more and more technology being invented, perhaps all of the secrets of the Giza Valley will someday be revealed.