She was a well educated and pragmatic daughter of an impoverished Prussian prince who grew into the longest-ruling female leader of the Russian empire and one of the most celebrated Russian rulers of either gender.

Under her reign, the empire was vastly expanded and grew in strength to such a degree that it became a force to be reckoned with throughout Europe.

Her name was Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst, more commonly known as Catherine the Great, the mighty Empress of Russia.

A strong advocate of reason and schooled in the Enlightenment doctrines, Catherine, apart from expanding it and making it vastly stronger, changed the appearance of the Russian empire completely.

A portrait of Catherine the Great by Danish painter Vigilius Eriksen. She was crowned an Empress on July 9, 1762, and ruled the Russian Empire for the next 33 years.

Catherine brought in Western culture and reformed the economy as well as the whole schooling system, the governance, and the legal system, making every man equal under the name of the law. She banned torture and abolished capital punishment.

All in all, she was good for the people. In fact, she was great, as the title bestowed upon her clearly indicates.

Catherine’s spouse Peter, on the other hand, not so much.

According to every account, Peter III of Russia was creepy, malevolent, and possibly bordering on insane. His wife in her memoirs described him as an inept, crude man-child and a drunkard unfit to rule an empire, who wished nothing but to play with toys or dress up as a general, place his servants in military outfits and play-act war games with them.

He was very good at it, he learned a lot playing around with his precious collection of toy soldiers inside his chamber.

Peter III

Catherine, a girl of prodigious intellect and great ambitions, was in for a surprise when she found out that all her husband ever wanted out of her was to dress her up as a soldier so he could put her through intense, rigorous military drills.

On one very notable instance, she found a rat hanging on the wall–it had been accused of treason and sentenced to death by hanging.

A portrait of Peter III of Russia as an Emperor. He succeeded his aunt Elizabeth, the Empress of Russia.

“One day, when I went into the apartments of His Imperial Highness, I beheld a great rat which he had hanged, with all the paraphernalia of an execution. I asked what all this meant. He told me that this rat had committed a great crime, which, according to the laws of war, deserved capital punishment,” she wrote, according to The Empire of Russia: Its Rise and Present Power, written by John Stevens Cabot.

The story goes that Peter, aside from the usual war games, play-acting scenarios he so much wished to be a part of, had developed on the side a weird obsession with toys. Particularly military ones.

Peter III depicted as emperor on a 10 ruble gold coin (1762)

Peter had a full chest of them tucked neatly under his bed, which he would pull out when there was no one around to bother him and spent hours meticulously arranging them in strategic formations all over his chamber.

His bedroom was his battleground, the toy soldiers his faithful military, and he was their mighty general.

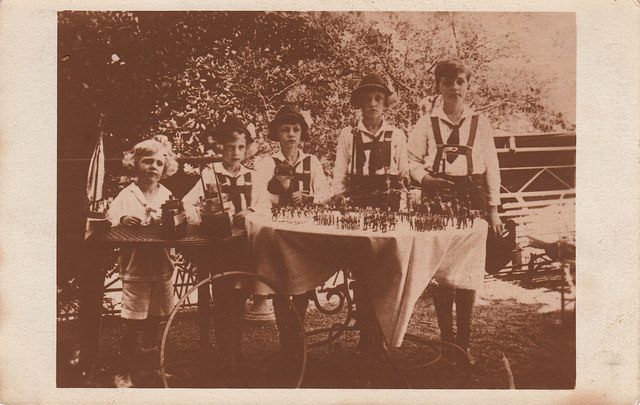

Princes of another family. From left to right: Archduke Rudolf (1919-2010), Archduke Carl Ludwig (1918-2007), Archduke Felix (1916-2011), Archduke Robert (1915-1996), and Crown Prince Archduke Otto von Habsburg posing with their collection of toy soldiers in 1924. Author: pellethepoet – CC-BY 2.0

But one day an intruder, a rat that came out of the woodwork, interfered with one of his elaborate battle schemes and chewed the head off of one of his toy soldiers. It was just getting started on chewing another one nearby when Peter’s dog caught him red-handed.

“It had climbed the ramparts of a fortress of cardboard which he had on a table in his cabinet and had eaten two sentinels, made of pith, who were on duty in the bastions.

His setter had caught the criminal, he had been tried by martial law and immediately hung; and as I saw was to remain three days exposed as a public example.”

The young Peter was infuriated by this and the rat, guilty of high treason was found hanging by Catherine on a tiny gallows her husband made especially for the occasion. “In justification of the rat,” she continues, “it may at least be said that he was hung without having been questioned or heard in his own defense.”

18th Century Portrait of Empress Catherine II of Russia

Hanging human beings was employed throughout the ages because of gravity. The weight of the human tightens the windpipe, cuts off any blood flow, and most often than not breaks the neck of the victim.

Unless the loop was tied tightly around the rat’s neck, the poor thing couldn’t have lost any blood flow nor choke to death. It would just hang there on the gallows until it starved to death, wondering what had just happened.

Monument of Peter III in Kiel Photo by: Рулин – CC BY-SA 4.0

It is said that Peter had a difficult early childhood that made him the psychopath he became. He was born in Germany as Karl Peter Ulrich and brought to Russia against his will by his aunt, Empress Elizabeth Petrovna, so he could rule after her.

A picture of a rat that looks as if it is begging. Collection of National Media Museum, circa 1902.

He could hardly speak Russian at the time and never really learned it, for he never wished to live in that country, let alone rule it.

Nonetheless, he was crowned emperor on January 5, 1762. Within six months was overthrown by his people in a coup–most probably organized by none other than Catherine herself.