When people started using mechanical clocks during the 14th and 15th centuries, they were introducing a relatively new concept of counting the time. Mechanical clocks, like the one of Salisbury Cathedral, were game-changers, since before then people didn’t cut the day into 24 slices. There were the “temporal hours,” but these marked time differently, as periods of the day and night. Temporal hours also varied with the changing of seasons, but when mechanical clocks stepped in, they helped standardize and measure the time in smaller increments.

Many horologists believe that the Salisbury Cathedral clock, dated back to 1386, is the world’s oldest such clock still capable of chiming the hour, though more of these Middle Age relics are in existence, chasing after the same title, hence debate is open.

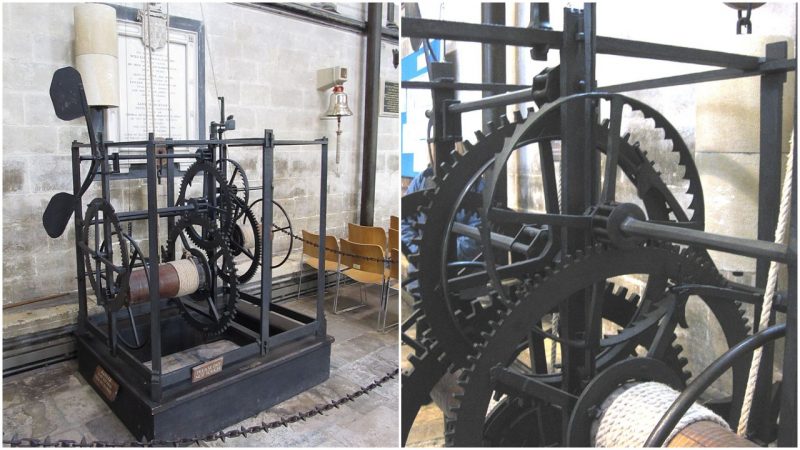

The Salisbury Cathedral clock is not the type of machine most of us are familiar with these days. It doesn’t have a clock face, just the naked workings set in an iron frame. The Salisbury clock was designed to chime the church bell every hour and call people to the service.

A relic from the Middle Ages, the mechanical clock in Salisbury Cathedral, set to operate a bell in the tower. Supposedly it was first installed in the cathedral around 1386 and was restored 1956. Photo: Rwendland – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

It is not the most beautiful clock piece around, as it doesn’t have too many parts nor has it great aesthetic valor, but the fact that it has been around since the 14th century raises its worth. Initially, the iron mechanism was installed in a bell tower that stood next to the cathedral until it was pulled down in 1792. The clock then resided in the Cathedral tower but was largely neglected after it was replaced in 1884. Forgotten by everyone, it was rediscovered in 1928, supposedly by a curious visitor.

The six-centuries-old timepiece underwent restoration in 1956 to get it back into working order. In order to chime the hour, the clock needs to be wound by hand. The mechanism moves as its larger wheels are first turned into motion, which consequently plays with weights that trigger the work of the cylinder bound with rope. It occupies the space of 3.9 square feet with most of its original parts kept in the 1956 restoration.

There has been considerable debate about the age of the Salisbury clock, though it seems clear that the clock was ticking at the town’s cathedral by 1386. Before this clock was in situ, other clocks fulfilled the function to call for the church service, including clepsydras.

The clock’s Striking Train, Photo: Cdenning, CC BY-SA 3.0

The mechanical clock was most likely commissioned by Bishop Erghum who later employed the same clock-makers to create another clock for Wells Cathedral, where he moved after his service in Salisbury. Producing the Salisbury clock had been a costly project for certain, and it probably took donations from almost every church-goer to cover the expense. Introducing the mechanical time tracking device would have changed the way people organized themselves around their daily chores.

The Wells Cathedral clock, said to be dated to 1392, is now stored at London’s Science Museum. The mechanism of appears slightly more improved as its medieval clock-makers also integrated an internal dial in its composure.

The Salisbury mechanical clock’s Going Train, Photo: Cdenning, CC BY-SA 3.0

Similar looking devices like the one in Salisbury or the one from Wells can be traced to other parts of Britain and continental Europe. Most of these pieces can be dated in the 15th century, yet there are some clock mechanisms that might be from the 14th century and remain contenders for the title of world’s oldest. One such clock sits in Beauvais, France, also in a cathedral tower, and was allegedly installed as early as 1305.

As mentioned, a significant majority believe that it is the Salisbury’s iron skeleton that makes it the world’s oldest. Now retired from its relentless daily task of counting time, the mechanism is currently used only for demonstrations.