You might think a certain global megabrand has a chokehold on all things coffee, but way back in the 15th century, a tiny southern Arabian country launched our love for the caffeinated concoction. Yemen had a world monopoly on coffee production for nearly 300 years.

How did the Yemenis come to revere caffeine? In various legends, a sheikh was traveling through Ethiopia when he saw birds behaving strangely, and observed that they were eating berries off a plant. The weary traveler tried the berries himself, and noticed immediately their perky power. (Another version has a traveler noticing goats eating the berries, to the same effect.) In another tale, a Yemeni priest was banished to a cave for bad behavior. On the verge of starvation, the priest reached for coffee berries. Because they were too bitter, he spit them out on a fire, and then noticed their redolent aroma, thus giving rise to roasted coffee beans.

While both stories are likely apocryphal, this much remains true: By the early 1400s, Sufi mystics in Yemen sipped coffee as a stimulant to keep them awake and alert during their epic chanting prayers to God. And coffee drinking soon spread from monasteries to newly created coffee houses.

Depiction of Rabi’a grinding grain from a Persian dictionary

The coffee plant was cultivated in the Yemen highlands and called by the Arabic name of qahwa, which morphed into the English variations of coffee and café. Yemen’s high-altitude terrain produced coffee beans with a distinctly earthy flavor reminiscent of wine and cherries.

View of Mocha, Yemen, during the second half of the 17th century

By the early 1500s, Yemen was exporting coffee through the bustling port of Mocha (or Al-Makha) to Egypt, Syria, Turkey, and beyond. Coffee became the driver of the Yemen economy and an agent of social change. Its consumption led to the rise of coffee shops, a place for men to gather to talk, listen to poets, and play chess; coffee shops became centers of social activity in major cities where the bean was imported. Indeed, the ascendancy of coffee shops posed a threat to the supremacy of mosques, which led some religious leaders to attempt to ban coffee in the mid-1600s. (The ban didn’t last. The people wanted their coffee.)

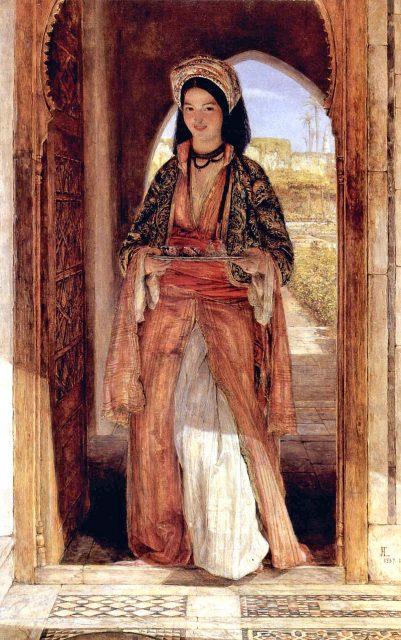

The Coffee Bearer, Orientalist painting by John Frederick Lewis (1857)

When the beverage showed up in Venice in 1615, the local clergy called it the “bitter invention of Satan,” according to the National Coffee Association, and asked the Pope to intervene. But the pope liked coffee and gave it his approval.

For centuries, the Yemenis closely guarded their coffee commodity. To keep their global monopoly, they refused to sell live coffee plants or seeds. Merchants came from all over to buy coffee in Mocha. It became known as Mocha coffee, though the beans weren’t grown there, and though it was nothing like a mocha you might get at Starbucks today.

But like any monopoly based on secrecy, it couldn’t last forever. By the 17th century, the dark black drink had become popular in Europe, and demand outstripped supply. In the 18th century, a wily Dutch cloth merchant named Pieter van der Broecke stole live coffee plants and smuggled them out of the country. Within 40 years, coffee plantations had sprung up around the world, in colonies in the East and West Indies, East Africa, Latin America, and the Indonesian island of Java, which gave rise to one of the oldest and best-known coffee blends, Mocha Java. Missionaries and travelers carried seeds far and wide. Coffee became one of the most highly sought out commodities. In the New World, Thomas Jefferson would call coffee “the favorite drink of the civilized world.”

Yemeni farmer collects arabica coffee beans at the plantation in Taizz, Yemen.

As the world caught up with coffee production, Yemen’s stranglehold on the trade loosened, and the port city of Mocha faded. Production slowed. In modern times, Yemen didn’t even participate in the International Coffee Trade Agreement of 1962, which set coffee quotas and shut Yemen out of the international coffee trade, according to a report in the L.A. Times., until the collapse of the agreement in 1989.

Coffee is still produced in Yemen today, though in much less quantity, and it lags far behind Yemen’s main export, crude oil. Yemen coffee is exported mainly to Asian countries. Some enterprising businessmen are attempting to capitalize on Yemeni history by encouraging farmers who grow qat, a narcotic leaf chewed daily by many Yemenis, to return to coffee bean production.