Belgium, the country of waffles, fine chocolate, and hundreds of different types of beer, is also a country of striking landmark sites, most notably cathedrals dated to the Middle Ages.

St. Paul’s Cathedral in the city of Liège, distanced some 60 miles from the capital Brussels, is noted for its statue of Lucifer, the fallen angel. A “tiny” detail: the statue that is there today is not the one originally installed in 1842.

The Liège cathedral was founded in the 10th century and underwent reconstructions from the 13th through 15th centuries. It was not until a 19th century restoration effort that Le génie du mal, or The Genius of Evil saw the light of day. The sculpture is widely known as the Lucifer of Liège in English.

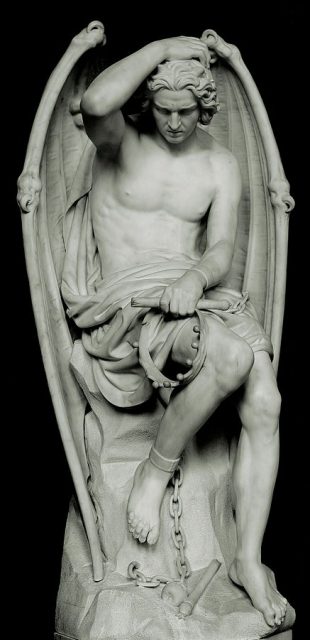

The Genius of Evil, Guillaume Geefs, 1848. Photo by I, Luc Viatour, CC BY-SA 3.0

The Neo-Gothic piece was created in 1848 by Guillaume Geefs, a prolific Belgian sculptor of the day, today noted for exploring sexuality and mythology through his artwork.

Guillaume’s 1848 assignment was not an ordinary one. The marble sculpture Le génie du mal was commissioned as a replacement for the original statue installed in the church, The Angel of Death, sculpted by Guillaume’s brother, Joseph.

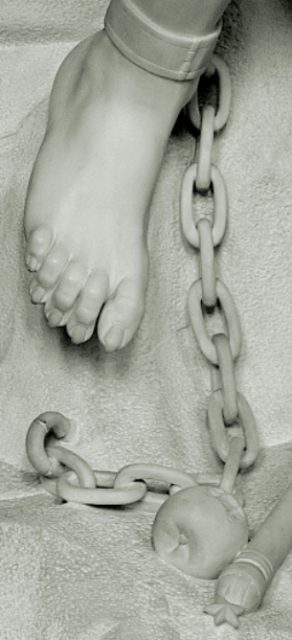

Detail of Le génie du mal: chained ankle, tasted apple, broken sceptre. Photo by Luc Viatour CC BY-SA 3.0

The Angel of Death was finished in 1842, and troubled church officials from the moment it found its place on the cathedral’s pulpit. Why? It was too sophisticated, too sublime, too bold to remain in situ at a sacred place such as Liège’s St. Paul’s Cathedral.

The sculpture was too angelic to give a sense it’s depicting the fallen angel, the one that Dante confidently placed in the ninth and the deepest circle of Hell, frosted in ice to his waist. In total contrast, the Lucifer of Joseph Geefs was too perfect. If it wasn’t for its bat-like wings and the snake coiled at his feet, one could easily conclude this was a sculpture of Apollo or Adonis.

The Angel of Evil, Joseph Geefs, 1842. Photo by Georges Jansoone (JoJan) CC BY 3.0

The masculine figure, as if this was the body of a perfect athlete, also had its knees parted — inappropriate! The sculpture hinted at a fascination with the figure of Satan, and if that was something acceptable in the circle of noblemen and Romanticists, church officials greatly found the piece disturbing.

It was deemed the piece as a bad influence especially for young people who attended the services. After only a year, the controversial sculpture was removed, and Guillaume was tasked to work on a new piece.

Horns, and a collocation of human and animal anatomy (detail) Photo by Luc Viatour CC BY-SA 3.0

While the original piece by Joseph offered a lot of flesh in one place, the replacement by Guillaume tried to compensate with multiple references to the theme of punishment. This does not mean that the new piece, which was completed in 1848, was spared from controversy.

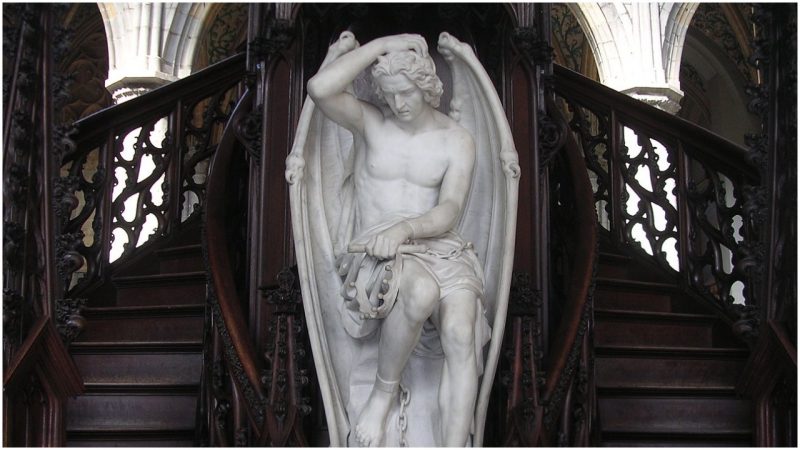

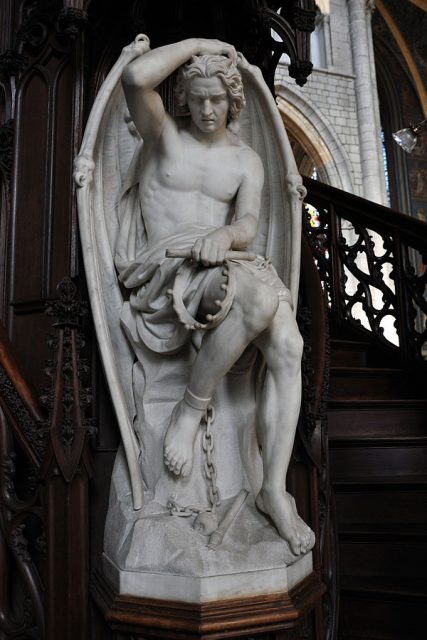

The pulpit of St. Paul’s Cathedral in Liège. It contains other figures associated with Christianity.

Lucifer was again depicted in stunning beauty, but at least Guillaume reduced the effect of overtly sexual imagery. Similarly to the original commission, this one too is naked except for the cloth worn about his waist. The bat wings are also there, taking the familiar vesica piscis shape, in an effort to still promote the holiness of the one depicted.

Judging by the expression of Lucifer, he is in a pensive mood, or maybe in agony. Perhaps he is overwhelmed by remorse, shame, and guilt. Or it is that Lucifer is now concerned about his impending punishment? He is chained by his ankle, with the one hand holding a crown and scepter broken in two. The broken scepter and the crown removed from his head hints at the fact that Lucifer has been stripped of his powers.

The Genius of Evil installed on the pulpit of the cathedral in Liège.

By the feet, besides a part of the scepter, is another symbol — the apple. The forbidden fruit, missing a bite, is a reference to the original sin in the Garden of Eden, an allusion also to humanity’s own downfall.

It is likely that both brothers intended a similar message with their depictions of Lucifer, that beauty can deceive, except Joseph went a bit too far. Whether or not Guillaume managed to diminish the overwhelming effect of eroticism is a question which can only be answered individually by spectators.

The too-seductive sculpture by Joseph Geefs can still be seen — not in any church but at the Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium.