A hot day in New York City feels like no place else.

The heaviness of the air weighs on you as you trudge down the blinding bright streets crisscrossing Gotham. It could be the concrete everywhere–sidewalks below, buildings above–and the smell of garbage that seems to grow in strength whenever the thermometer climbs above 85 degrees.

What doesn’t help is that construction picks up in the summer, and the screech of jackhammers and drills penetrates deep into your brain.

The 1966 song “Summer in the City” by Lovin’ Spoonful captures it perfectly: “Hot town, summer in the city/Back of my neck turning dirty and gritty/Been down, isn’t it a pity/Doesn’t seem to be a shadow in the city.”

42nd Street, just west of Seventh Avenue, New York. 1970s. Thanks to the ruthless mob boss Carmine Galante, heroin flooded the city.

There are refuges to be found–an air-conditioned home, store, movie theater, even a subway car. Jones Beach, Coney Island, and Far Rockaway beckon. Or a patch of shade in Central Park in Manhattan, Prospect Park in Brooklyn, or one of the city’s other treasured nature preserves.

It’s safe to say that Joe & Mary’s Italian American Restaurant on 205 Knickerbocker Avenue in Bushwick, Brooklyn, was not one of those hot-weather refuges on July 12, 1979.

It was 87 degrees when Carmine Galante, 69, showed up for lunch at Joe & Mary’s with his entourage. However, he led his group to a spot not inside but at a table in the quiet patio garden out back.

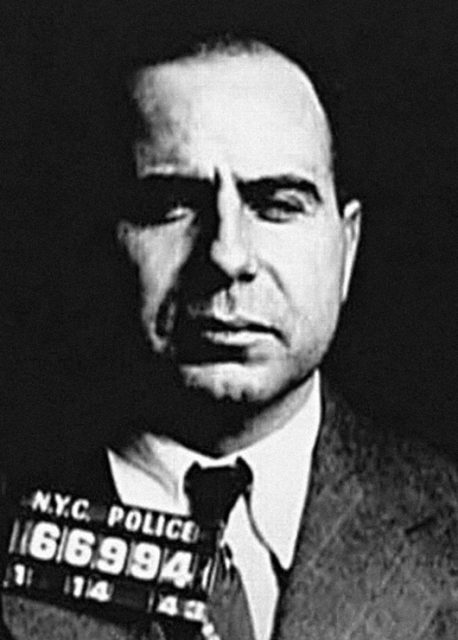

Carmine Galante when arrested for narcotics

Galante, the head of the Bonanno crime family for some five years, was in the middle of a vicious period of power plays in the Five Families of the mafia.

A popular-with-the-mob Brooklyn restaurant might not seem the most secure place for lunch. This stretch of Knickerbocker Avenue was a place where first- and second-generation Sicilian-Americans came to hang out.

However, Galante appeared to thrive in the tense atmosphere and was famous for saying, “No one will ever kill me, they wouldn’t dare.”

It turns out, they would.

Galante was nicknamed “the Cigar” because one was perpetually jammed into his mouth. He had a cigar going when he walked into Joe & Mary’s and in so doing turned the restaurant, sometimes called a luncheonette, into one of the most famous New York City crime scenes of the late 20th century.

Born on February 21, 1910, in East Harlem, New York, Galante came from a family with roots in Castellammare del Golfo, Sicily. He began his mafia career as a driver for Joseph Bonanno and worked his way up to consiglieri, believed to be personally responsible for at least 80 murders.

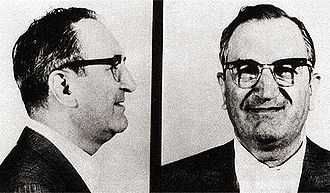

Mugshot of Joseph “Joe Bananas” Bonanno, who was boss from 1931 to 1968. Galante was loyal to him.

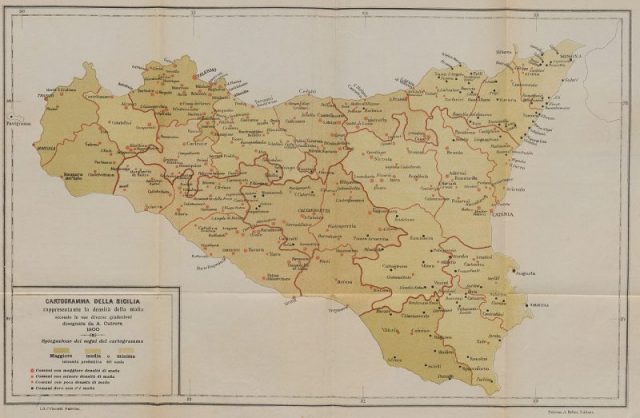

Galante was present during a key meeting in Palermo in 1957 when the Sicilian and American mafia decided to work together to flood the United States with heroin.

The New York City mob’s role in controlling drugs was to become a key to the spike in hard-drug use in the U.S. in the 1960s and 1970s.

There were violent power struggles over drug distribution among the mob families, with some holding back from trafficking as the laws against it became more severe, and others jumping in deeper. The fact that Galante was nicknamed the “Heroin Don” gives a strong hint of where he stood.

A 12-year prison sentence for narcotics only solidified Galante’s terrifying reputation. One prison doctor described him as “a psychopathic personality.” Said an associate in a later documentary on the Bonanno family, “People were afraid of him.”

1900 map of Mafia presence in Sicily. Towns with Mafia activity are marked as red dots. Galante formed a partnership with Sicilian Mafia to form a billion-dollar heroin empire.

Selwyn Raab wrote in the respected book Five Families, “Balding, bespectacled, and with a bent walk, Galante was another don whose demeanor contradicted the popular image of a Mob narcotics predator and assassin. To passersby, the chunky, five-feet four-inch tall Galante looked like a relaxed, retired grandfather as he selected fruits and vegetables at Balducci’s market in Greenwich Village … Yet he was a man who had been in serious trouble with the law since childhood, a man with an unsurpassed underworld resume of viciousness.”

After Galante made parole, he took charge of the Bonanno family (Joseph Bonanno had been forced into retirement by his mob rivals), wracking up huge profits in the illegal drug trade. He also seemed to be trying to become the most powerful New York boss of all, after the death of Carlo Gambino.

Carlo Gambino, who headed another family. After Gambino’s death in 1976, Galante thought he should be the number 1 Mob boss in NYC

And he was not exactly laying low. The New York Times devoted a story to him on February 22, 1977, with the headline “An Obscure Gangster Is Emerging As the Mafia Chieftain in New York.” In the story, the reporter said, “No man in organized crime is getting more attention from Federal and local law enforcement officials than Carmine Galante.”

A police lieutenant was quoted as saying, “Not since the days of Vito Genovese has there been a more ruthless and feared individual. The rest of them are copper; he is pure steel.”

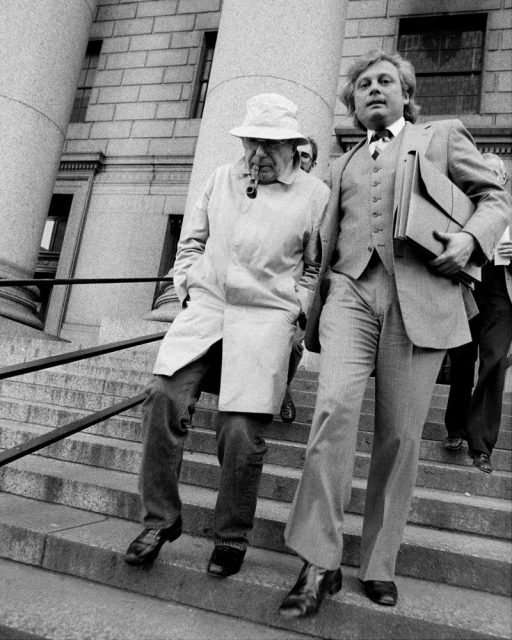

Unlike flashy mafia dons like John Gotti, Galante dressed simply. His “job” as far as the straight world was concerned was operating the L&T Cleaners at 245 Elizabeth Street in Little Italy, and he did stop by there many mornings but always surrounded by his tough, cold-eyed, young bodyguards recruited from Sicily. Although he was married, he spent most of his nights with a mistress on East 38th Street.

Carmine Galante leaves Manhattan Federal Court with his lawyer Michael Rosen. (Photo by NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images)

Interestingly, he could speak three languages and was known to quote St. Augustine, Plato, and Descartes.

It was widely known that the other mobsters in New York considered Carmine Galante power-crazed and greedy. He was ripe for a rivalrous attempt on his life, but that didn’t keep Galante from going out to lunch that hot July day in Brooklyn.

Galante’s distant cousin owned Joe & Mary’s, and the reason for his stopping by was to have lunch and say goodbye to that relative, Joseph Turano, who was leaving for a vacation to–where else?–Sicily. His two bodyguards were with him, Baldo Amato and Cesare Bonventre, as well as a drug dealer, Leonardo Coppola. The group ate a meal of fish, salad, and wine.

Before coffee and dessert arrived, Galante lit a cigar.

The unthinkable (to Galante) happened when three men in ski masks ran into the restaurant and barged into the patio at about 2:45 P.M. Shots rang out, and Carmine Galante, Coppola, and Turano were all killed. As for the two bodyguards, they did nothing during the attack or afterward. They simply left the restaurant.

Morgue attendants carry the body of Carmine Galante from Joe & Mary’s Restaurant on Knickerbocker Ave. in Brooklyn. (Photo by Charles Ruppmann/NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images)

“He must have stepped on someone’s toes,” commented the New York chief of detectives who came to view the crime scene that afternoon.

And what a scene it was. Galante was shot in the eye, hurled backward from his lunch table, covered by a floral oilcloth, and into a small tomato patch. His cigar was still clenched in his teeth, and the newspaper photographs that captured his death grimace were soon an indelible part of mafia lore.

Undercover agent Joseph D. Pistone, alias Donnie Brasco. He informed on the Bonanno family.

When the coroner had Galante’s body taken out on a stretcher from Joe & Mary’s, it passed beneath a sign reading, “We Give Special Attention to Outgoing Orders.”

Who was behind the hit? It turned out the mafia commission itself authorized the assassination and bought off the bodyguards, offended that Galante was trying to corner the heroin market entirely and become more important than any other boss.

As for Joe & Mary’s, it achieved fame as the locale of a major mob hit, but that couldn’t keep it in business forever. Despite being included in newspaper stories like “After Violent Incidents, Restaurants Can Thrive or Drive,” it eventually closed.

And although Salvatore “Sally Fruits” Farrugia was appointed by the commission to replace Galante, the Bonanno Family was never again one of the most feared mob families in New York.