It was Mary Stuart, the doomed, charming, and controversial Queen of Scotland, who said shortly before her death, “In my end is my beginning.”

But even Queen Mary might have been astounded by how fascination with her life and her dramatic execution on February 8, 1587, in Fotheringhay Castle has never abated.

In December 2018 a movie about the relationship between Mary, Queen of Scots and England’s Elizabeth I will be the latest big-screen version of the cousins’ deadly rivalry. In this film, directed by Josie Rourke, Margot Robbie will play Elizabeth I and Saoirse Ronan will play Mary.

Mary, Queen of Scots, portrait by François Clouet, c. 1558–1560.

The most history-minded are finding fault with a scene in the film’s trailer showing the two queens in the same room, exchanging fury, because history says they never met in person, even though Mary was under a form of house arrest in her cousin’s kingdom for 19 years.

But overall, there is tremendous excitement over a big-budget, A-list, lavishly costumed look at the queens who ruled countries in the 16th century, both of them charismatic, daring, and attractive. Mary married three times; Elizabeth, never.

The ‘Darnley Portrait’ of Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I was the younger daughter of Henry VIII and Mary was the only child of King James V of Scotland, Henry’s nephew. The two countries were definitely not in harmony for parts of the 16th century. After a failed war he launched on England, King James turned his face to the wall and died, leaving tumultuous Scotland to be ruled by his newly born daughter (regents ruled in her place of course).

Mary’s mother being a French noblewoman, the child queen was more or less smuggled out of Scotland to marry the French heir to the throne, the Dauphin, later Francis II. Their marriage is the subject of the TV series Reign, which fans have adored even while it takes extreme liberties with the historical record.

Mary in captivity, by Nicholas Hilliard, c. 1578.

After Mary’s husband died young, she at last sailed to Scotland to begin her personal rule at the age of 19. Six years and two husbands later, Mary was more or less run out of Scotland by her nobles. She had a choice: Get military help from France, the country she grew up in, filled with relatives who were, incidentally, Catholic like herself. Or cross the border into England, and ask her second cousin Elizabeth, a Protestant queen, for help in getting back her throne.

She chose the latter, and never saw freedom again.

Mary’s all-white mourning garb earned her the sobriquet La Reine Blanche (“the White Queen”).

In fairness to Elizabeth, Mary was a threat to her from the time Good Queen Bess took the throne. Catholic Europe did not recognize the marriage of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, Elizabeth’s parents, as legal and therefore she was deemed illegitimate and unfit to be a queen, in their eyes and in particular by edict of the Pope. Mary even claimed the throne of England while she was in France. She later pressured Elizabeth to name her the successor so often in letters it approached harassment.

Queen Elizabeth initially showed some sympathy for Mary’s cause once she was driven out of her kingdom, but under pressure from her councilors and from the government of Scotland, Elizabeth said she could not support Mary with money and troops until she had been cleared of the murder of her second husband, Lord Darnley. Scandalous rumor said that the Earl of Bothwell was behind Darnley’s murder, with the connivance of Queen Mary. He denied it, but it didn’t help create an atmosphere of innocence that Bothwell and Mary married.

With the use of letters that are now believed to have been forged, Mary’s enemies made a strong case that the Queen had murdered Darnley, the father of her son, James VI.

A young Mary, Queen of Scots, and her husband, Francis II of France, shortly after his coronation.

And so Mary was not given assistance but instead confined in large country houses, to her bitter resentment. Conspiracies followed, aimed at freeing her. But some of those plots involved the assassination of Elizabeth as well.

Sir Francis Walsingham, Elizabeth’s spymaster, laid a trap for Mary, using a double agent to convey letters that were in code to her French friends and relatives and, later, a young Englishman named Anthony Babington who dreamed of liberating her. In a letter to him, Mary approved of his plot to free her and depose Elizabeth with violence. Walsingham’s operatives broke the code.

Sir Francis Walsingham.

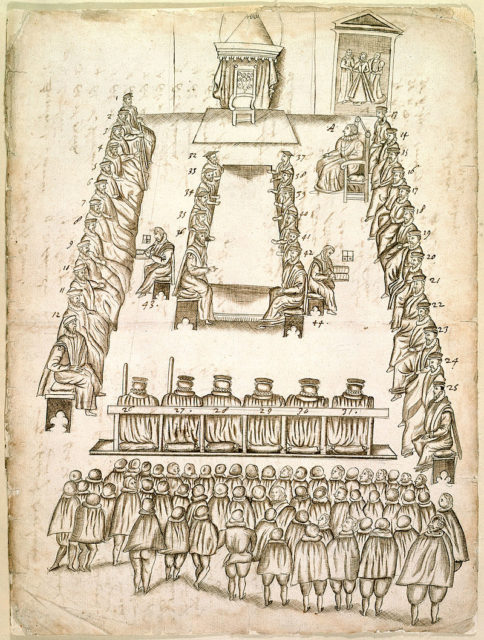

In 1586, Babington and Queen Mary were both arrested for treason. He was tortured, condemned, and executed horribly: hanged, drawn, and quartered. As for Mary, she underwent a form of trial, although she was given no counsel for her defense; she spoke up for herself with spirit and intelligence. Her guilt, however, was a foregone conclusion.

On February 7, 1587, Mary was told she would die the next day. She prepared for her execution calmly, praying and writing farewell letters dividing her belongings.

A scaffold was built in the Great Hall of Fotheringhay Castle for her death, before the leading noblemen of the kingdom.

The motte of Fotheringhay Castle. Photo by Iain Simpson CC BY-SA 2.0

An eyewitness to her death said she entered the room “full of grace and majesty.” She wore a red dress, to evoke the color of martyrdom. When the axeman asked her forgiveness, as was the tradition, she said, “I forgive you with all my heart, for now, I hope, you shall make an end of all my troubles.”

Mary laid her head on the block, and the executioner struck. It took three blows to completely sever her head. Wrote the eyewitness, the executioner then picked up her head to announce to the crowd “God save Queen Elizabeth! May all the enemies of the true Evangel thus perish!”

Drawing of the trial of Mary, Queen of Scots, October 14–15, 1586.

But in so doing, he pulled off her red wig and revealed her hair had gone completely white, even though she was 44. She had the head of an elderly woman. “It was not old age …. but the troubles, misfortunes, and sorrows which she had suffered, especially in her prison.”

Copy of Mary’s effigy. The original, by Cornelius Cure, is in Westminster Abbey. Photo by Kim Traynor CC BY-SA 3.0

When Queen Elizabeth was told of her cousin’s harrowing end, she angrily denied she had ordered the execution, even though she had signed the warrant. No one believed it was done without her knowledge. The Spanish Armada sailed in part to avenge her death.

After Elizabeth died, Mary’s son, James VI of Scotland, became James I of England in 1603.

And while many venerate the “Golden Age” of Gloriana, the present day Queen Elizabeth is directly descended from Mary Queen of Scots.