Nov 23, 2018 Barbara Stepko

It was 1868 when Thomas Niles, the publisher of Louisa May Alcott, recommended she write a book about girls, one that would have widespread appeal. Alcott wasn’t thrilled with the notion, but she needed the money.

It took her just a few weeks to pen Little Women and expectations were not high: Alcott would write in her journal, “Never liked girls or knew many, except my sisters, but our queer plays and experiences may prove interesting, though I doubt it.”

Alcott couldn’t have been more wrong, of course.

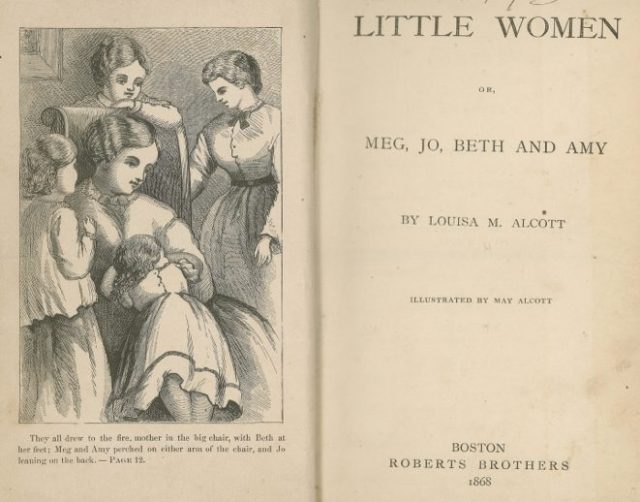

Little Women (1868).

Little Women — a much-loved classic about the spirited March sisters and their struggles during the Civil War era — has become one of the most beloved books in literature.

It may have been set centuries ago, but the empowering story has left an indelible mark on girls everywhere, with themes, such as the importance of family and embracing one’s dreams, that remain every bit as relevant today.

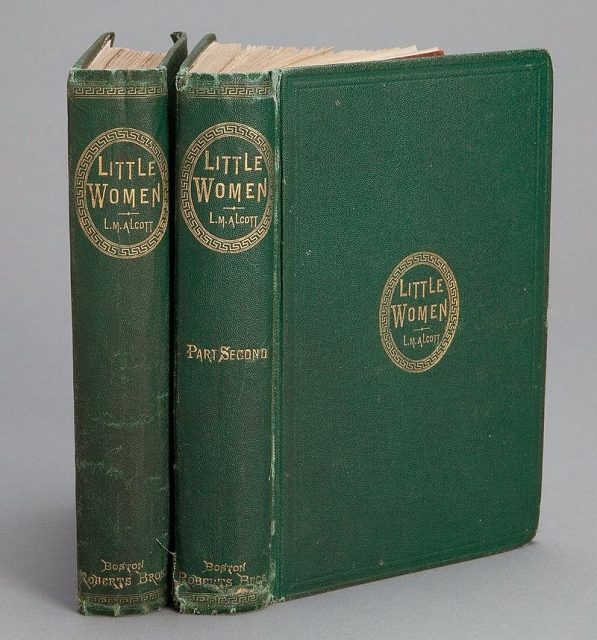

Both volumes of Little Women

Reading the book, or watching any of the movies adapted from the classic (yet another go-round — this time starring Meryl Streep, Saoirse Ronan, and Emma Watson — is slated for release in December of 2019), one can’t help but wonder: How much of the story was autobiographical? As it turns out, parts of Alcott’s real life did indeed influence the book, and, in certain respects, is no less astonishing.

Here, the stories behind those remarkable Little Women:

Anna

The oldest March sister, romantic Meg, is based on Alcott’s real-life oldest sister Anna Bronson Alcott. She too was proper, willingly accepting the constraints that the Victorian era imposed on women.

Though a talented actress — she and Louisa loved to put on plays and started the Concord Dramatic Union — Anna believed the only way she could escape from her humble beginnings was to marry. She would write, poignantly, in her diary, “I have a foolish wish to be something great and I shall probably spend my life in a kitchen and die in the poor-house.” Anna would meet her husband-to-be, John Bridge Pratt, at the theater company she started with her sister. The couple had two sons, but Pratt died about ten years after their marriage. With the royalties from Little Women, Alcott helped support her sister and nephews, and even helped Anna purchase Henry David Thoreau’s house in Concord.

Lizzie

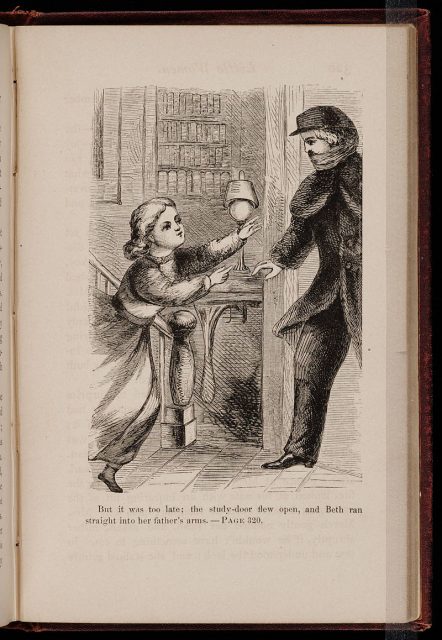

Elizabeth Alcott was fictionalized as Beth March in Little Women (1868).

The third March sister is based on Alcott’s sister by the same name, Elizabeth, called “Lizzie” by her family. A shy, gentle soul, Lizzie was a homebody who loved kittens and sewing. As in the book, she did contract scarlet fever after holding a sick baby belonging to a poor family to whom she delivered much-needed essentials. Though Lizzie would initially recover, she died two years later in 1858 at the age of 22. The kind character of Beth in Little Women is Louisa’s loving tribute to her sister.

Abigail May

Elizabeth Alcott was fictionalized as Beth March in Little Women (1868).

A charming but spoiled artist, who finds love with the family’s next-door neighbor, Amy is based on the youngest Alcott sister, Abigail May, who went by her middle name. Like her character, May embraced the finer things in life, particularly fashionable clothes and the fine arts.

She trained as an artist in Boston, but many American art teachers didn’t offer their female students the same level of training as their creative male counterparts (studying musculature and sketching naked limbs was considered untoward). With the success of Little Women, Alcott paid for May to study art abroad.

Abigail May Alcott Nieriker

Apparently, May made quite the impression, gaining recognition as a painter (in 1877, the Paris Salon displayed one of her still lifes) and socializing with notable artists of the day, such as Impressionist painter Mary Cassatt.

The feisty young woman would eventually help other female artists fight discrimination and pursue their dreams. May settled in Paris, married Swiss businessman Ernest Nieriker in 1878, and gave birth to a baby girl, Louisa May (“Lulu”).

Seven weeks later, May died of an infection resulting from the birth. Since May’s husband traveled often for work, she requested their daughter be sent to live with her namesake, Aunt Louisa. The little girl would become the inspiration for Louisa’s last completed work, 1888’s Lu Sings. She would raise the little girl until her death in 1888. Lulu would reunite with her father in Zurich, Switzerland.

Louisa May

Louisa May Alcott

As any Little Woman fan knows, the second-oldest March sister — spunky, independent, and opinionated Jo — was based on the author herself.

Louisa May Alcott was a free-spirited tomboy who loved exploring nature and climbing trees, but the Civil War would bring an end to her lively pursuits. Alcott, working as a nurse, contracted typhoid pneumonia (though doctors now believe she may have suffered from an autoimmune disorder).

The attic at Fruitlands where Alcott lived and acted out plays at 11 years old. Note that the ceiling area is around 4 feet high.

She never fully recovered and was frail for the remainder of her life. Writing would be her savior. Louisa May’s first book, Hospital Sketches, a fictionalized memoir of her war experience, was a success.

Louisa May Alcott

In 1868, at the request of her publisher, Louisa May penned another book, this one for girls: Little Women. It would become a success — a bittersweet one, at that. Alcott became something of a celebrity and had trouble dealing with her newfound fame. (Reporters and strangers alike would linger by her home, hoping to catch a glimpse of the writer and perhaps get an autograph.) Although Louisa May would go on to write a sequel of sorts, she longed to tackle adult fiction. Eventually, she would get a chance, but never achieved the same kind of success.

Her work ethic, though admirable, would take a toll on her health. Louisa May Alcott’s biographer, Susan Cheever, would write, “Anyone who dreams of wealth and fame might be warned by this story of a woman who struggled so hard to make money that by the time she reached her goal she could no longer appreciate its benefits.” Louisa May died of a stroke, at age 55 — single and independent until the very end.

Though she had received a marriage proposal decades earlier, her personal freedom was something she would come to savor. “I’d rather be a free spinster,” Louisa May Alcott wrote in her journal, “and paddle my own canoe.”