For a man whose career began with handling animals that were already dead, famous taxidermist Carl Akeley sure had his share of run-ins with animals that were alive.

During his career, Akeley survived being crushed by an enormous bull elephant, nearly plunged off a cliff in flight from the rolling body of a silverback gorilla he had just shot, and barely escaped being trampled by three angry rhinos.

His wildest near-death experience was on his first trip to Africa, where he was attacked by a revenge-seeking leopard that he managed to kill using his bare hands.

It’s safe to say he was not a friend to the animals at this point in his life.

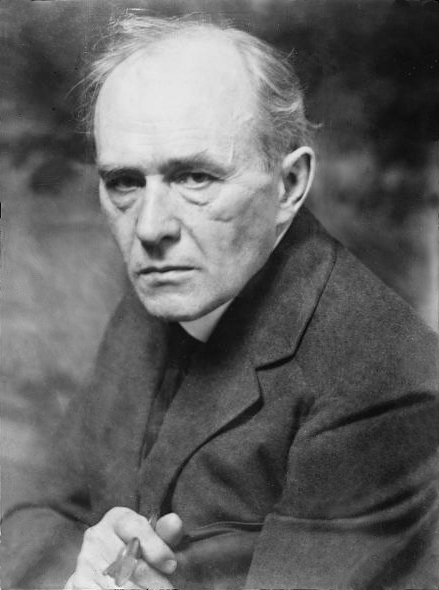

Photograph of taxidermist Carl Ethan Akeley

Nonetheless, Akeley’s first claim to fame was preserving P. T. Barnum’s famous circus elephant Jumbo, tragically struck and killed by a train in 1885.

Akeley had recently been fired from Ward’s Natural Science Establishment for sleeping on the job, but due to his talent in resurrecting animals through his taxidermy work, his boss called him in right away to work on Jumbo.

In 1896, Akeley was promoted at the Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History, becoming the museum’s chief taxidermist.

To bring in new exotic animals for the museum’s collection, Akeley departed for Africa to hunt. He was not content with working on animals that died of natural causes, clearly.

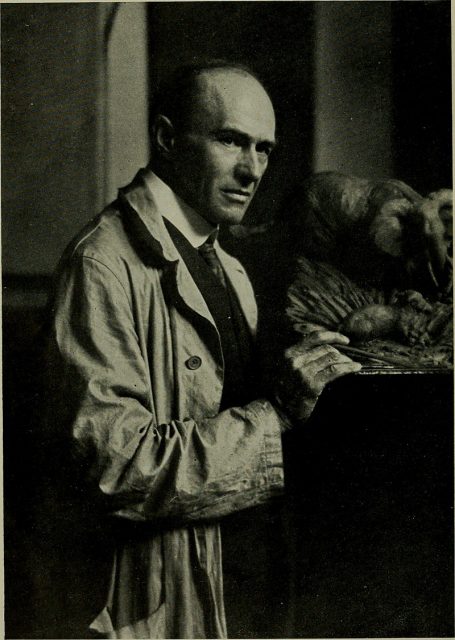

Mr. Carl E. Akeley, c. 1914

After an unsuccessful four-month journey full of delays, Akeley grew frustrated that he still hadn’t caught an animal. It was when he arrived at Ogaden, in Eastern Ethiopia, that he, the hunter, would become the hunted.

Akeley, feeling determined, set off from his camp with hopes of finding a potential specimen.

Not long into his journey, he shot and killed a hyena. Unfortunately, the hyena wasn’t desirable due to a skin disease so he abandoned his kill and continued his trek. (Clearly, these priorities would not be looked on with approval today.)

After a short while, Akeley and a “pony boy” who was leading a mule came upon a warthog.

After shooting it, Akeley decided to leave the carcass there, because he wasn’t entirely satisfied.

“Muskrat Group”, one of Akeley’s early works for the Milwaukee Public Museum Photo by: Evan Howard CC BY-SA 2.0

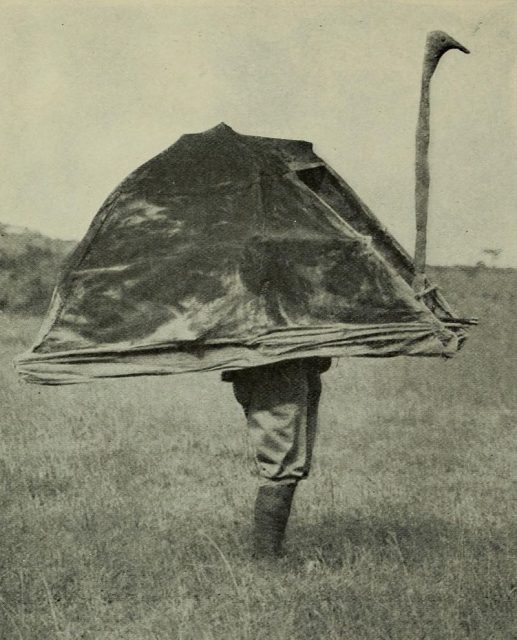

He finally spotted a pair of ostriches. He followed them, but they were too quick and fled.

Feeling unfulfilled, Akeley and the youth accompanying him returned to their camp to pick up the tools they needed so they could finish what they started with the warthog.

To their surprise, they arrived to find only a bloodstain in the dirt as they watched a hyena scurry off with what was left of the wild pig.

Discouraged and exhausted, they headed back toward their camp to retire for the evening. Along the way, he noticed the hyena that he had killed earlier had disappeared.

All that remained was the dead hyena’s trail; evidently, a serious predator made it when dragging the carcass into the bushes. Akeley stood there with the youth as he heard rustling coming from the hedge.

Without thinking, he shot off his gun in the direction of the noise and immediately regretted his thoughtless act. He felt even more regret when he heard the growl of an animal he recognized as a leopard and not a hyena coming from the bush.

Assuming (and hoping) the leopard was wounded, Akeley figured he would leave and come back to find the dead leopard in the morning.

Well, Akeley might have been finished for the night, but the leopard wasn’t. On his way back to camp, he spotted the leopard only 20 yards away–when the cat started coming for him.

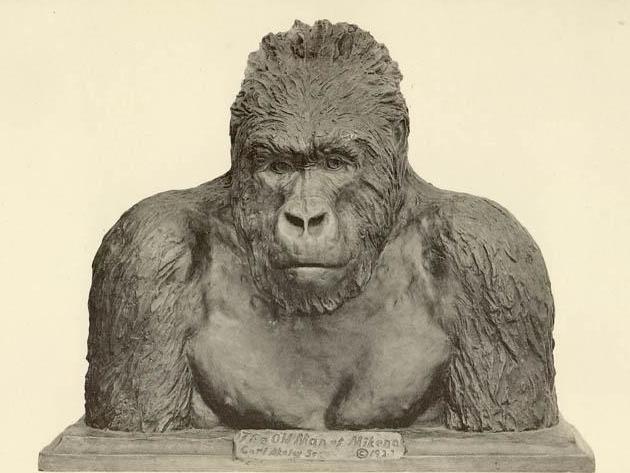

The Old Man of Mikeno, bronze bust of a mountain gorilla by Carl Akeley

In Akeley’s autobiography, In Brightest Africa, he wrote, “I again began shooting, although I could not see to aim. However, I could see where the bullets struck as the sand spurted up beyond the leopard. The first two shots went above her, but the third scored. The leopard stopped and I thought she was killed.”

In a day that was full of assumptions, Akeley was wrong again. The leopard began to charge at him when he raised his rifle, only to find that the magazine was empty. “For just a flash I was paralyzed with fear, then came power for action,” he wrote.

Akeley ran for his life while he tried to reload his cartridge.

At this point, he turned to shoot, but it was too late–the 80-pound leopard, before he knew it, was pummeling him.

“Her intention was to sink her teeth into my throat and with this grip and her forepaws hang to me while with her hind claws she dug out my stomach, for this pleasant practice is the way of leopards.”

Mr. Akeley impersonating an ostrich

Fortunately for Akeley, he had injured the wild cat’s hind leg when he first shot. In his biography, Akeley wrote:

“Instead of getting my throat she was to one side. She struck me high in the chest and caught my upper right arm with her mouth.

This not only saved my throat but left her hind legs hanging clear where they could not reach my stomach.

With my left hand I caught her throat and tried to wrench my right arm free, but I couldn’t do it except little by little.”

Wrestling the leopard to the ground, Akeley called for the youth’s help. When he didn’t receive a response, he realized it was only him and the leopard in a battle of wills.

“I still held her and continued to shove the hand down her throat so hard she could not close her mouth and with the other, I gripped her throat in a stranglehold.”

Akeley felt the leopard growing weaker as her struggling ceased. He finally let go and stood up so he could find the boy.

White-tailed deer in summer – composition at Field Museum (Chicago). Author – Carl Akeley (1864-1926) Photo: Mike Shelby

CC BY 2.0

The youth appeared with his knife, which Akeley used to finish the leopard off, making sure she was finally dead.

Due to the adrenaline rushing through his body, Akeley didn’t realize until after the fight was over how severely injured he was. He made it back to his camp to learn that his fellow companions heard the gunshots during his battle.

According to Akeley, they figured he had gotten into a brawl with natives or a lion and that either way he’d be dead before they could get to him–so they continued to eat their dinner.

Upon arriving at the camp, his camp-mates were shocked when they saw Akeley was covered in blood and his clothes ripped to shreds.

They sprang into action, cleaning Akeley’s chewed-up arm with antiseptics and preparing the surgical tools. His pain promptly caught up with his injury.

Akeley wrote, “The antiseptic was pumped into every one of the innumerable tooth wounds until my arm was so full of the liquid that an injection in one drove it out of another. During the process, I nearly regretted that the leopard had not won.”

While Akeley was recovering in a tent, members from the camp brought the defeated leopard’s body and laid it down next to his cot.

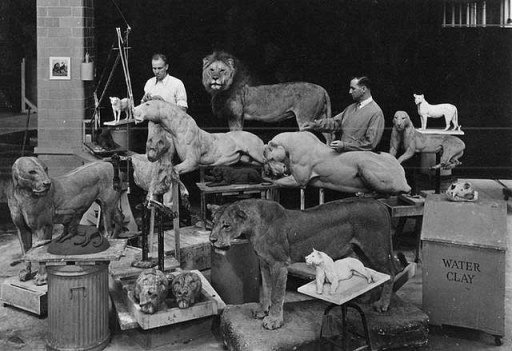

Carl Akeley preparing lions for lions diorama

Akeley analyzed the leopard’s battle wounds and, despite a bullet wound striking her right hind leg and one that skimmed along the back of her neck, it was Akeley’s bare hands and forcible grip that saved his life.

Akeley made a full recovery and went back to Chicago. Although he barely won the fight against the leopard, it didn’t stop him from continuing his hunting excursions.

It wasn’t until 1921 that he began to question the morality of hunting animals for sport–gorillas specifically.

After nearly a decade of killing wildlife, Akeley started his work to preserve the life of gorillas and successfully established Africa’s first wildlife sanctuary in Congo in 1925.

The Gorilla Expedition Leaving New York

The following year and during his final journey to Congo, he contracted a hemorrhagic fever and died. He was buried in Africa, not far from where he killed his first gorilla.

He’s now considered the father of taxidermy, and there’s a hall named in his honor inside the American Museum of Natural History.

His work was carried on with the help of his second wife, Mary Jobe Akeley, who advised the expansion of Akeley’s wildlife sanctuary in 1929.

Today Carl Akeley is remembered and honored less for his hunting and credited more with preventing the extinction of Mountain Gorillas in Africa.