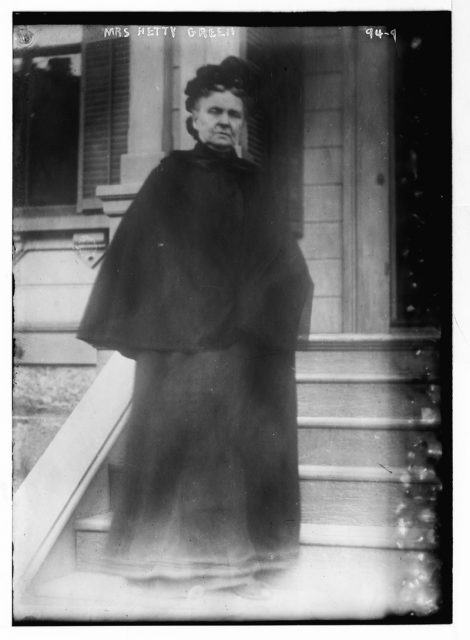

She wore a simple black dress with frayed hems and clutched a black handbag as she marched along the crowded streets of Lower Manhattan, talking to no one. The sight inspired some to refer to her unkindly as the Witch of Wall Street.

She kept an office at Chemical Bank, where she pored over her investment strategy. When she died at age 81, in 1916, the New York Times called Hetty Green the “wealthiest woman in the United States.” At the time, she had in liquid assets alone an estimated $100 million. Or in today’s dollars, $2.3 billion. (Today the richest woman in the U.S. is Alice Walton, a daughter of the Wal-Mart founder, with a net worth of $38.2 billion, according to Forbes magazine.)

Henrietta “Hetty” Howland Robinson was born November 21, 1834, in New Bedford, Massachusetts, the only daughter of a prosperous Quaker whaling family—an odd combination that presaged both her astonishing wealth and peculiar parsimony. (A younger brother died in infancy.) Because of her mother’s delicate health, young Hetty was often left in the care of her father and grandfather, who bred in her a healthy respect for money. At an early age, she learned to read stock market reports.

Hetty Green

Though Hetty showed an aptitude for finance in her teens, it wasn’t until her early 30s that she received the funds that would allow her to become essentially a professional investor. Her father died in 1865, leaving her the family fortune of $5 million. When her Aunt Sylvia died shortly thereafter, bequeathing $2 million to charity, an incensed Hetty challenged the will in court, raising eyebrows by producing an alternate will that was later ruled a forgery. She had a knack for real estate deals, snapping up foreclosed properties, buying and selling railroads. She issued high-interest loans to desperate banks and cities in crisis. “I buy when things are low and nobody wants them,” she told the New York Times in 1905. “I keep them until they go up and people are anxious to buy.” In one particularly astute move, she sensed in 1907 that the market was overvalued, and called in all her loans. When the market crashed, she swooped in and bought low, the very model of a modern vulture capitalist.

Paranoid that men were after her money—and they were—she didn’t get married until she was 33. Edward Henry Green had his own relatively modest wealth, though he wasn’t as clever or as thrifty as his wife. They had two children, Ned and Sylvia. Money put a strain on their relationship: where she was disciplined, he was free-wheeling. She tried to keep her finances separate from his in an era where that was unheard of. Edward eventually moved out of the house, but when he became ill, she nursed him in the months before his death. Hetty adopted a widow’s simple black dress “of the plainest material,” according to a 1909 article in the Washington Post, for the rest of her days.

Hetty Green with her Terrier

Despite her wealth, the extremely frugal life she led hints at an obsession bordering on instability. Her children wore second-hand clothes. When her son injured his leg in an accident, she took him to a free clinic for treatment and left when doctors recognized her and demanded payment. The leg didn’t heal properly and had to be amputated. She treated herself for a hernia by jamming a stick in her abdomen and holding it in place with her underwear.

She was not unaware of the figure she cast and seemed to resent the opinions some had of her. “I am not a hard woman,” Hetty Green told a reporter. “But because I do not have a secretary to announce every kind act I perform, I am called close and mean and stingy. I am a Quaker, and I am trying to live up to the tenets of that faith. That is why I dress plainly and live quietly. No other kind of life would please me.”

As she aged, her odd ways became more pronounced. She moved frequently, to deflect attention from the press or would-be robbers. She slept with a chain of bank-deposit keys around her waist and a gun tied to her hand.

Hetty Green

“Mother held herself aloof because there was nothing else she could do in her position,” her son, Colonel Edward H.R. Green, told the New York Times in a story published July 4, 1916. “When it becomes known that a person has money to lend you have no idea of the requests that come for it.” He went on to say it distressed his mother that the press reported that in her black purse she was carrying bonds. Not true, the Colonel said. She was carrying lunch and toiletries.

Hetty Green died at the age of 81, in 1916, after a series of strokes. “Although Mrs. Green was one of the wealthiest women in history and owned a controlling interest in the Louisville & Nashville Railroad, she did not own a private car,” her obituary in the New York Times noted. “Avoidance of ostentation was one of her rules of life, and up to the time she went to her son’s home she lived in a little apartment at 1,233 Bloomfield Avenue, Hoboken.”

After her death, her children indulged in the kind of lives that would make her roll over in her grave. Son Ned became a collector with a taste for the finer things in life. When daughter Sylvia died in 1961, she left almost her entire estate to charity.