As Margaret Dickson was consigned to the gallows on Edinburgh’s historic Grassmarket on September 2, 1724, it is unlikely that anyone attending her public execution thought they would see the woman alive again afterward.

The day of the hanging should have been just another ordinary day, with a routine proceeding on the schedule: the hanging of a woman sentenced to death.

Her public death was certainly observed by both court and church representatives, family members and relatives, and probably other people who were there just for the grim entertainment of the hanging event itself.

Grassmarket, with Edinburgh Castle towering above it. Photo by Kim Traynor – CC BY-SA 3.0

There was one little incident which was resolved quickly. John Dalgliesh, the woman’s hangman, had left Dickson hands-free, and she attempted to relax the noose.

But the crowds were quick to throw a stone or two at the hangman, and prevent any manipulation. The woman was eventually ‘hanged for the usual length of time’ and her body was claimed by family members who carried on to give a proper funeral.

Western end of Grassmarket, painted in 1845.

From Edinburgh, the cart carrying the coffin with the seemingly dead body was to be taken to Musselburgh, Dickson’s place of birth. However, the funeral party never reached Musselburgh.

With Edinburgh behind their back, the group accompanying Margaret’s body stopped for drinks and refreshments at Peffermill. The coffin with the body in it was left outside the local inn, which is when it happened: the moment of “resurrection,” according to the several varying versions of the story.

Noise and sounds were heard coming out from inside the coffin. Against all odds, Maggie Dickson was alive.

Maggie was held in Old Tolbooth before the trial.

But why was the woman sentenced to capital punishment? Several versions exist of how Maggie Dickson committed the crime of infanticide, leaving the lifeless body of her newborn on the bank of a river.

The year was 1723 when Maggie’s routine life as a fish and salt vendor spun out of control. Maggie was in her early twenties, and her husband, a fisherman, went absent from the family home.

Maggie was working as a fish vendor, her husband was a local fisherman.

Like many other details concerning Maggie’s story, the reasons why she was left without a husband are not entirely clear. He could have gone away to work for the fisheries in Newcastle, perhaps to make some extra cash, or could have simply abandoned his wife. Soon, Maggie needed to find other ways to support herself.

She ended up working in an inn, probably in the small burgh of Kelso, in the Scottish Borders area. Things got complicated as Maggie, aged 22 at that point, found a love interest in the son of the innkeeper and became pregnant.

Maggie Dickinson faced the gallows in Edinburgh’s Grassmarket for the crime of Concealment of Pregnancy.

Keeping the child was an issue, for several reasons, including the fact that she was still married and the baby was illegitimate, and that the father of her undesired baby was younger than her.

The options were scarce for women like Maggie Dickson in those days. For one, she couldn’t afford to lose this job, as otherwise she would be left on the street. Maggie tried to conceal her pregnancy, probably as long as she could. We are not certain how successfully that went on, and the baby eventually arrived prematurely, either alive or it may have also been stillborn.

What counts for a fact: the lifeless body of the infant was found the same day Maggie left on the bank of Tweed River. It is said she was unable to toss the tiny body in the depths of the flowing waters.

The young woman was likely frozen, overwhelmed by the entire situation, something she reportedly tried to communicate and use in her self-defense later on, as her wrongdoing was revealed. The woman also claimed she delivered the baby prematurely and that she was in such an extreme state of pain, it left her unable to look for any help.

River Tweed. Photo by Illmarinen CC BY-SA 3.0

In the eyes of law, it was of no importance whether Dickson had gone through a miscarriage, or if she indeed killed her own child; she was violating the Concealment of Pregnancy Act. It was for this crime that she was sent to Edinburgh to face a trial.

So what would happen to Maggie after she apparently re-awoke from death? According to Scottish law at the time, and to what officials later on also agreed, her punishment had already been carried out.

Grassmarket in Edinburgh: shadow of the gibbet delineated in paving on the site of public executions, next to the Covenanters Memorial from 1937. Photo by Kim Traynor – CC BY-SA 3.0

The woman was hanged once, so would not be subjected to the gallows again. It was seen as “God’s will” that she carried on living.

Maggie was reunited with her husband and had several children with him. She also resumed with her duties as fish and salt vendor.

It is also said, after her hanging, Dickson, who was not much of religious person, would dedicate one day every week to prayer and fasting until the end of her life. The exact date when she died is also unclear; some of the last accounts suggesting she was alive are dated to 1753.

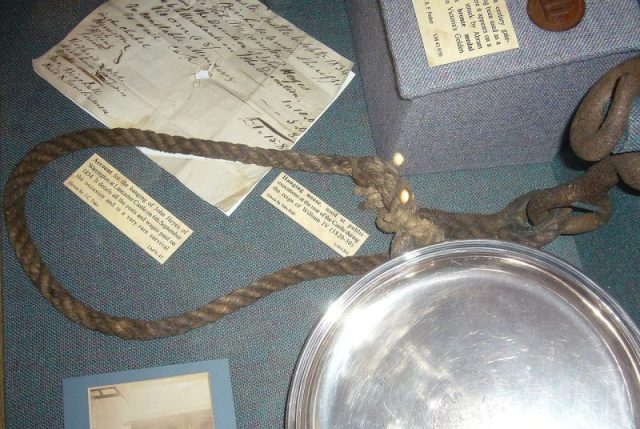

Hanging noose used at public executions outside Lancaster Castle, c. 1820–1830. Photo by Nabokov CC BY-SA 3.0

Did her case had any direct implications on the laws concerning public execution by hanging? Maybe. The case was a much-debated matter back in the 18th century.

Maggie’s case, in general, had attracted a lot of public attention, making her sort of local celebrity. People started calling her Half-Hangit Maggie.

In Edinburgh today, she is also remembered with Maggie Dickson’s pub. Some people believe she did manage to manipulate the noose in some way that saved her from strangulation.

Maggie Dickson’s Pub, Grassmarket, Edinburgh. Photo by Md.altaf.rahman CC BY-SA 3.0

Changes in Scottish law concerning death penalties were implemented in 1790. For example, that year, hanging replaced burning as the preferred method of capital punishment, for wrongdoings done on the grounds of treason.

It was also around this time that the legal vocabulary concerning the sentence of hanging was also slightly altered. In Maggie’s time it only read that the convict should be “hanged,” now the sentence was revised with two extra words: “hanged until dead.”