The Vintage News

Nov 11, 2017 Shahan Russell

World War I was fought from 28 July 1914 to 11 November 1918. Because many of the combatants had colonies and alliances beyond the continent, it drew in others from around the world. And due to the technological advances at the time, over 9 million soldiers and more than 7 million civilians died.

WWI would change the map of Europe and end in such a way that made WWII inevitable. Despite its impact, even today there’s a lot that many don’t know about this conflict.

1. Soldiers of the Allied Powers and the Central Powers celebrated Christmas together

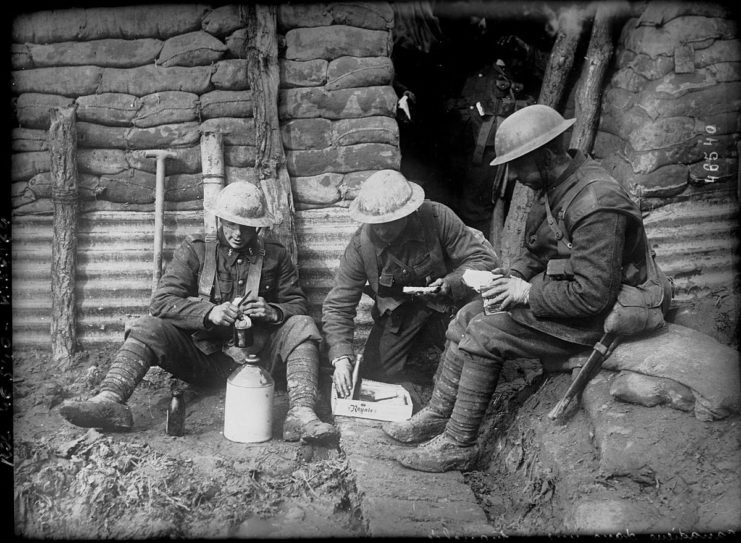

This is known as the Christmas Truce. By September 1914, both sides found themselves well-ensconced in trenches. The Germans were trying to break through into France, while the Allies were determined to avoid that and push them out.

As Christmas approached, ceasefires were called so both sides could bury their dead. But on December 25, something very strange happened. As many as 100,000 British and German soldiers put aside their guns, shook hands, and exchanged food and gifts. By 1915, however, as the casualties grew, the camaraderie ended and there were no more truces.

2. Aviators from both sides got along

Even after the Christmas Truce ended, Allied and Central pilots continued their camaraderie. It’s believed they saw themselves as a breed apart, and that flying distanced them emotionally from the horrors below.

In 1915, a German pilot who was downed behind Allied lines was first wined and dined by Allied aviators before they handed him over to the military. When an “enemy” pilot was shot down, aviators of the other side would fly over enemy territory to drop a note, letting them know if the downed pilot died or was taken alive into custody.

3. The war forced Britain to improve healthcare services for its people

Although the country entered the war at the height of its wealth and power, very little of that wealth reached the vast majority of the British people. Malnutrition was so widespread, that of the millions who applied to become soldiers, almost 40% had to be rejected.

Today, the average height of an adult British Caucasian male is about 5’9”. In 1914, their average height was 5’2”, though a member of the upper class stood about 5’6” These findings shamed the government into providing subsidized health care for common people.

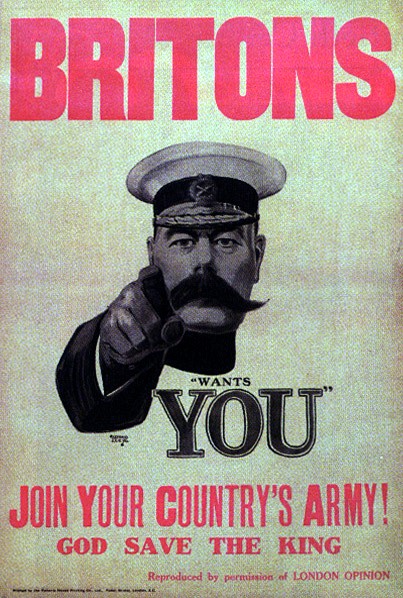

4. Millions of minors served in the military

The official age required to become a recruit was between 18 and 19, but it was rarely enforced. Poverty and desperation forced many to lie about their age because they needed jobs and food. There were an estimated 250,000 minors from Britain, alone, the youngest being 12; while Canada sent over 20,000 minors.

Desperate for soldiers, some countries were willing to look the other way, while others, like France, encouraged boys as young as 15 to join. Once in, they were treated the same as the older men. Many died, as a result.

5. Canadian troops were feared by the Germans

Though most people think of Canada as a peaceful nation, Canadian soldiers developed a fierce reputation during the war. The Germans called them Sturmtruppen (storm troopers), because of their success in seizing enemy trenches and for taking extreme risks.

The Canadian soldiers also led the Allies to victory at the battles of Vimy and Passchendaele, which the British and French had failed to take. Whenever the Germans realized that Canadian forces were advancing, they prepared themselves for the worst. It’s perhaps no accident that Canadian soldiers were the highest paid among the Allies.

6. Canadian troops also had the highest rates of venereal disease

One out of every nine Canadians contracted some form of VD, six times higher than the average British soldier. For punishment, they had their pay suspended while they underwent treatment, and were required to pay a fine for every day they were out of action. To make it worse, infected soldiers were banned from taking leave for 12 months.

Since Canadians soldiers were the highest paid, they could afford to stay in hotels with private baths, which shocked most hoteliers. Such wealth must obviously have delighted their female “friends,” however.

7. Many British nurses were aristocratic volunteers

To support their troops, several high-class British women set up First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY). To join, one had to pay a fee, as well as provide monthly expenses for supplies. Since many came from wealthy families, they’d take their cars to France, then convert them into ambulances – again at their own expense.

Although they rendered valuable, often dangerous service at the risk of their own lives, they were not always well-received. Back then, women were expected to be subservient to men, but these were wealthy aristocrats who refused to obey the traditional norms.

8. High-ranking Allied POWs in Germany were trusted to stay put

Although low-ranking POWs were subjected to terrible conditions, high-ranking ones were generally trusted to stay put. Germans simply had them sign a document called a parole. Once they did, top brass POWs could leave their prison camp and go shopping in nearby villages and towns if they had money.

It was so effective that none who signed the parole actually tried to escape. One British officer claimed he planned to buy supplies in a German village for his escape, but once he signed the parole, honor bound him to stay.

9. Some Allied POWs were allowed to stay in hotels

As the war progressed, Germany found itself with far more POWs than it could handle. Those of rank who were badly injured or mentally shattered were sent to neutral Switzerland or Holland for better medical treatment.

Others were allowed to stay in hotels if they had money, and have their families over for visits. There were so many Canadian POWs in Scheveningen, Holland that they set up a baseball club which played against a club set up by American POWs. So long as they were no longer fighting, Germany didn’t care.

10. More than half of the French Army mutinied in 1917

No one is sure exactly when it started, but a series of defections began in Northern France sometime after they lost at the Second Battle of the Aisne in April 1917. By then, the French had lost over a million soldiers, and they’d had enough.