Ever wondered why Greenland, three-quarters of which are covered by the only permanent ice sheet outside Antarctica, has in its name the adjective “green”? On the other hand, Iceland, consisting of the words “ice” and “land,” seems a bit too green to live up to that name.

Well, one internet theory claims that this was indeed intentional―the Vikings who settled in Iceland considered the island habitable, so they named it Iceland, hoping that the name would be enough to discourage other European peoples attempting to make their own settlements. They named Greenland to achieve quite the opposite, as they didn’t care if anyone was willing to colonize the iceberg in the freezing ocean. However, this theory is highly unlikely.

In order to get to the bottom of this paradox, an investigation was conducted by National Geographic, in which the magazine went deep into different chronicles and sagas, together with modern scientific facts.

First of all, the Viking’s toponyms are quite simple; the newly discovered territory would most likely be named by combining the word “land” with the first thing that was noticed upon arrival. For example, Leif Eriksson named the Canadian east coast Vinland, as he saw wild grapes growing near the shore.

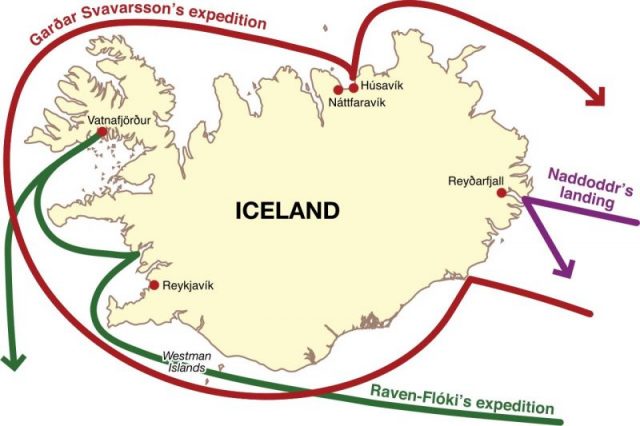

As for Iceland, according to the Sagas of Icelanders, which chronicles the country’s history from the 9th to 11th century, the Norse explorer called Naddador was the first to reach the island in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. What he saw there was snow, so he named the place Snæland or “snow land.”

Garðar Svavarsson, artists imagination. Photo by Artūras Slapšys – CC BY-SA 3.0

Naddador was followed by the Viking colonizer Garðar Svavarosson, who was more into naming the country after himself, probably making a precedent in the established tradition. So, Garðarshólmur (“Garðar’s Isle”) became the next name under which today’s Iceland was known.

But the reason why Iceland bears such a grim name today is related to the island’s next colonizer, Flóki Vilgerðarson. Flóki’s trip from the mainland was marked by the loss of his daughter, who fell from the boat and drowned in the open sea. Soon upon arrival, the livestock he brought with him died.

According to the sagas, this string of unfortunate events was crowned when Flóki Vilgerðarson climbed a nearby mountaintop from which he observed a fjord, laced with icebergs. Depressed and enraged, he christened the country Iceland―a name which stuck to this day.

A map indicating the travels of the first Scandinavians in Iceland during the 9th century

Despite Flóki’s efforts to discourage further colonization of the island, upon his return to Norway, a rumor was spread by one of his seamen known only as Thorólf that the country was fertile and rich, just waiting for settlers. Mass migration to Iceland began soon after.

Kangamiut village in the middle of nowhere, Greenland May 2015

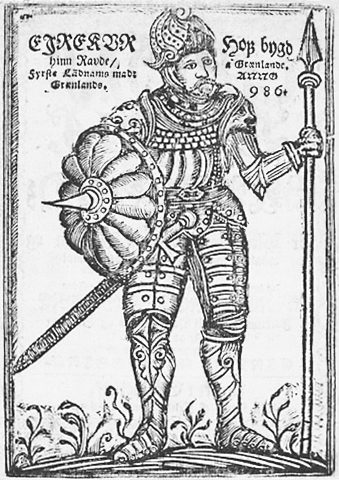

Greenland, on the other hand, was discovered in 982 A.D., when Erik the Red, the father of Leif Eriksson, landed on the southeastern part of the island. Today we can determine through the analysis of ice cores and mollusk shell data that in the period between 800 and 1300 A.D., the average temperature in Greenland was significantly higher than it is today.

Erik embarked on his journey as a consequence of exile from Iceland after he killed three people during a feud. The Icelandic old law demanded death or exile, so he chose the life of an adventurer on the open seas.

Eric the Red

Sailing westwards, he embarked for the shores of a huge island he deemed suitable for a settlement. A saga which chronicled the travels and discoveries of this almost mythical figure in the Norse tradition referred to the anecdote which led to the naming of the newly discovered land:

“In the summer, Erik left to settle in the country he had found, which he called Greenland, as he said people would be attracted there if it had a favorable name.”

Fjadrargljufur canyon with river and big rocks. South Iceland

So, basically, the name was part of Erik’s marketing strategy through which he hoped to assemble future settlers and cultivate the new world.

Of course, the country was already inhabited by Inuit natives, who called the island Kalaallit Nunaat, meaning “The Land of the People.” The name is still in use among the Greenlandic Inuit population.

Strangely enough, some predictions concerning global climate change are indicating that soon enough a climate shift could lead to radical temperature drops in Iceland, while Greenland could experience a rise on the thermometer. This could happen in a period of 200 years. If it does, the names given more than 1,000 years ago would turn out quite prophetic.